It’s more than 50 years since I was sitting in front of my family’s black-and-white television, watching the action from the Olympics in Mexico City.

Never before had the Games impacted on my life and never since have they failed to provide tales of triumph and tristesse, political scandals, international boycotts, drugs controversies and a giddy whirl of the best and worst of human behaviour.

I was in Sydney in 2000 and travelled down to London 12 years later to sample the fervent atmosphere of millions of people from hundreds of countries joining in the planet’s biggest party and there have been myriad occasions where amazement and applause has been matched by a communal feeling of “I was there…”

This year, in a new Covid landscape, almost nobody WILL be there, apart from the competitors and officials and assorted IOC panjandrums when the torch is ignited at the Tokyo Games on Friday.

The pandemic means there will be no supporters at the venues and even the medal ceremonies will be carried out between the competitors themselves, while the BBC plays crowd noise on an endless loop.

It’s far from an ideal scenario, but the Olympics always have the capacity to provide shock and awe in Sumo-sized dollops.

Here are just a few of the many occasions since 1968 when these games without frontiers have made the world sit up and take notice.

1968: The black power protest

It happened more than 50 years before the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, but there was still a sense of prejudice being tackled head-on when Tommie Smith, the 200m champion in Mexico City, stood atop the medal podium and delivered a black power salute alongside his compatriot John Carlos.

The incident horrified many officials and shockwaves reverberated thereafter as Smith eloquently explained how his anger at racism and injustice in his homeland had been the catalyst for the unprecedented show of solidarity between the athletes.

A spokesman for the IOC argued that Smith and Carlos’s actions had been “a deliberate and violent breach of the fundamental principles of the Olympic spirit”.

But participants had been allowed to make Nazi salutes at the Berlin Games 32 years earlier, and Smith’s defenders were as quick to point that out as the runner had been swift on the track – recording a winning time of just 19.83 seconds.

1972: A beaming smile amid tragedy

The Munich Games will always be remembered for the killing of 11 members of the Israeli team by the Palestinian Black September group.

It was an act that summed up the febrile political situation that threatened to derail the Olympics in that decade.

Mary Peters, thankfully, offered some respite from the gloom that pervaded the event in the aftermath of the massacre.

The Northern Irishwoman was thought to be past her best after finishing fourth and ninth in the pentathlon at the two previous Olympics.

But she never stopped believing in her abilities and produced a series of outstanding performances to secure the gold medal, narrowly beating the local favourite, West Germany’s Heide Rosendahl, by 10 points, and setting a world record score.

Her utterly joyful smile on the podium was like a rainbow in a thunderstorm.

After her victory, a series of death threats was phoned into the BBC. But, despite all the intimidation, Peters insisted she would return home to Belfast, where she was greeted by thousands of fans and a band at the airport and paraded through the city streets.

She later won the BBC’s Sports Personality of the Year.

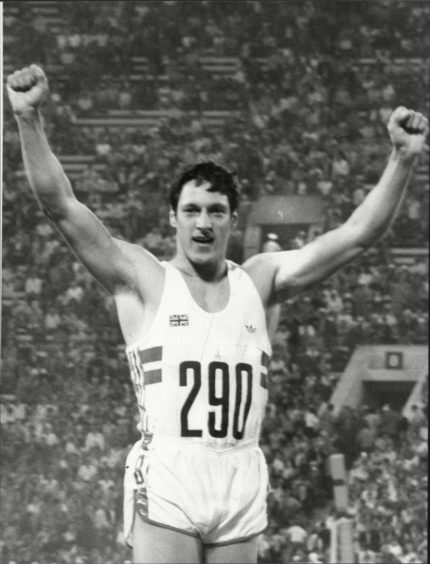

1980: The Flying Scotsman in Moscow

There was no shortage of pressure on Allan Wells’ rugged shoulders in the controversial build-up to the Olympics in Moscow.

The Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan at the end of 1979 had sparked calls for a boycott and the United States and China were among the countries who withdrew from the Games.

Wells was one of the athletes who were urged by the British Government not to participate in Moscow – and he later told me how he received pictures of dead Afghani children in the mail from the government to try to dissuade him from competing.

But he stuck to his guns, put his body through the wringer and, backed by his wife Margot, sprinted into the history books when he surged out of the blocks to edge out the pre-race favourite, Silvio Leonard of Cuba, by the thinnest of margins.

It was a magnificent piece of theatre, capped by a triumphant outcome.

Some people argued that Wells’ achievement had been made easier by the absence of the Americans who traditionally dominated the event.

But, just a fortnight later, he beat them all at a track meeting in Koblenz in West Germany and one of them, Mel Lattany, told him: “For what it’s worth, Allan, you’re the Olympic champion and you would have been Olympic champion no matter who you ran against in Moscow.”

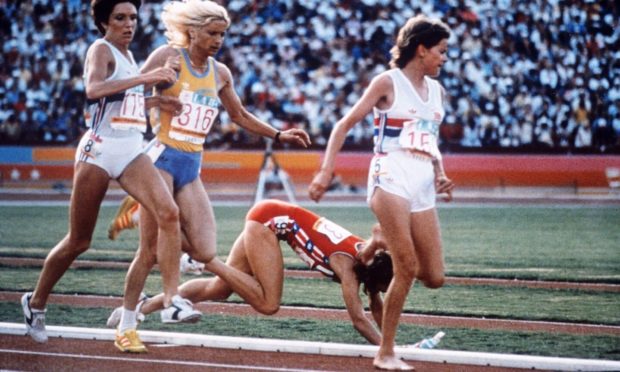

1984: Mary’s hopes nipped in the Budd

It was billed by the American media as a lip-smacking clash between their golden girl, Mary Decker, and a barefoot South African teenager, Zola Budd, who was representing Great Britain after being fast-tracked into the team.

However, one of the most eagerly-anticipated showdowns at the Los Angles Games finished in a blizzard of acrimony when the two women collided and Decker was sent sprawling off the track during the 3,000m final.

The duo had kept such close tabs on one another, both before and during the race, that it was almost inevitable there would be a coming together.

But still, when it happened, and the US star was left lying prostrate on the ground, her hopes dashed even as her rival looked aghast, it became one of the most iconic images in Olympic history.

Budd took the lead for a short time afterwards, but a chorus of boos reverberated around the arena and, as she admitted later, she was psychologically affected by the crowd’s partisan response and drifted out of contention, finishing in seventh place, far behind the gold medalist, Romania’s Maricica Puica.

Her attempt to apologise to Decker was met with a furious “Don’t bother” from the American. And these words summed up the whole miserable affair.

It later emerged that Budd’s father, Frank, had orchestrated his daughter’s move to England and banked the £100,000 the Daily Mail paid for the rights to her story.

His lifelong ambition was to shake the Queen’s hand and be worth a million pounds, but he was murdered in 1989 by a South African farm hand.

1988: Battle of the hormone monsters

It was less a sports event than a science experiment: the 100m men’s final in Seoul, which has been described as the “dirtiest, druggiest race in athletics history”.

The main culprit, Canada’s Ben Johnson, was briefly a new world-record holder after defeating the reigning champion, Carl Lewis, in a time of 9.79 seconds. So far, so inspirational, but it didn’t take long for the stench of drugs to rear its head.

Two days later, Johnson was stripped of his gold medal and world record and issued with a ban by the IOC after testing positive for the banned substance, stanozolol.

The gold was then awarded to the original silver medalist, Lewis.

But things soon grew murkier. Lewis had tested positive at the Olympic trials for pseudoephedrine, ephedrine and phenylpropanolamine and, looking back, it’s remarkable he was allowed to compete.

Silver medalist, Linford Christie, was found to have metabolites of pseudoephedrine in his urine after a 200m heat at the same Olympics, but the Briton claimed it was because he had drunk too much ginseng tea.

Of the top five competitors in the race, only one of them, former world record holder and eventual bronze medalist Calvin Smith never failed a drug test during his career.

No wonder he later said: “I should have been the gold medalist.”

1996: The Greatest makes poignant return

He was the boxer who floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee: the imperious, wise-cracking rebel with a cause who transcended sport and became an international icon.

Later in his life, it seemed dreadfully cruel that Muhammad Ali should be forced to battle with Parkinson’s syndrome, the one fight he couldn’t win and which deprived him of his once-fertile powers of oratory and fertile wit.

But even here, his sheer totemic presence, power and indomitability sent out an inspirational message.

At the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, he emerged with a tangible determination to ignite the Games spirit – even to the extent where he was burned by the torch.

I can remember the tears welling up in my eyes as I watched this once-wonderfully lithe and athletic man struggle to make his way towards the podium.

But he managed it, and you could detect his determination to show the world that he was still a king, all those years on from his heavyweight achievements.

It was the high point of the whole Olympics, which were later engulfed in drugs scandals and a terrorist bomb.

But Ali put his stamp of greatness on the proceedings.

2008: Lightning strikes in Beijing

Every so often, a personality comes along whose sheer talent, effervescence and star power strikes a rich chord with people who have little or no interest in sport.

Athletics had taken a dreadful battering in the previous two decades from myriad cases of substance abuse and doping bans – to the extent that many viewers tended to react to new records being broken with the same degree of cynicism they showed towards Tour de France sensations, especially after Lance Armstrong’s disgrace.

But there was none of that with Usain Bolt, the Jamaican athlete with a majestic gait and an innate joie de vivre as he announced himself on the global stage in China.

He triumphed in both the 100m and 200m, shattering existing milestones in the process and leaving his opponents chasing shadows.

NBC commentator Tom Hammond set the tone when he covered the 100m, where Bolt won in 9.69 seconds, despite slowing down as he neared the tape.

Hammond said: “And a fair start, Asafa Powell, Usain Bolt is also out well. Here they come down the track. USAIN BOLT! SPRINTING AHEAD, WINNING BY DAYLIGHT!”

He was similarly breathtaking in shattering Michael Johnson’s 200m world record, powering home in 19.30 seconds.

A new champion had arrived: a man who dominated the next two Olympics as well.

2012: A Scottish legend in Lycra

Chris Hoy has never taken the easy road to success, but his unprecedented achievements mean it wasn’t a surprise when he emerged as an overwhelming winner among readers in our poll to find Scotland’s greatest Olympian.

The cyclist, who achieved a total of seven Olympic medals, six gold and one silver, gained 42% of the votes, twice as many as Andy Murray, who came in second with 21%, followed by Chariots of Fire athlete Eric Liddell with 13% in third.

Hoy had already demonstrated his prowess, professionalism and pitch-perfect temperament with a series of outstanding displays in Beijing.

But by the London Games he was 36 years of age and others were pursuing him in the quest for podium places.

Would Hoy still have the requisite va va voom when it mattered? Or was this a chapter too far?

Of course it wasn’t. Instead, the Scot excelled throughout his Olympic swansong, not just as an ambassador for the London extravaganza and as Team GB’s flag carrier at the opening ceremony, but where it really mattered – in the velodrome.

First, he won gold in the team sprint with his colleagues Jason Kenny and Philip Hindes and then repeated the feat in the Keirin to overtake Steve Redgrave and become his country’s most successful-ever Olympian.

Even now, nearly a decade later, he remains an inspiration.