The spirit of competitiveness has always burned brightly in Liz McColgan.

Whether sweating on a treadmill on Christmas Day or pounding the streets of Whitfield in Dundee in the wind and rain, this redoubtable individual has always been as fragile as a Highland stag.

There’s the story of how, at the age of 11, the girl born Liz Lynch was beaten in a race by an older runner.

It was her first loss and it stuck in her craw. The youngster stormed home to her parents and told them: “She’ll not beat me ever again.” And she didn’t.

Some athletes mellow with age or take refuge in past laurels but whether excelling in front of her home crowd at the 1986 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh or sealing a place on the medal podium at the Seoul Olympics two years later, McColgan’s ceaseless drive, determination, thrawn streak and inner quest for perfectionism have all combined to make her Scotland’s greatest-ever female athlete.

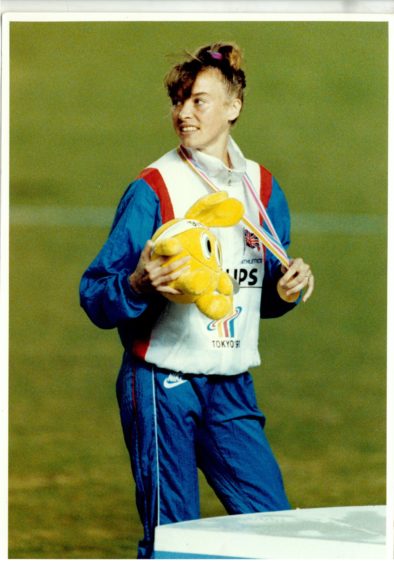

And that reputation was imprinted on the global consciousness 30 years ago this month when she left the rest of an international field trailing in her wake as she surged to victory in the 10,000m at the World Championships in Tokyo.

It was one of the most remarkable performances in Scottish sporting history but it didn’t happen without lashings of hard graft and high intensity behind the scenes.

The route to that Japanese triumph on a searing August evening was the culmination of a tireless work ethic that became synonymous with McColgan’s single-minded pursuit of plaudits and prizes.

Nothing was easy, nothing was handed to her, but the travails and tristesse taught her the virtues of making your own way in the world.

From her teenage days, she dedicated herself to running, to winning and creating a very personal pathway to success.

She briefly took jobs in a chip shop and a jute factory to support her athletics career before her uncle paid for her to study at the University of Alabama.

It was an important learning experience and McColgan’s steely desire and determination meant she ran hundreds of miles every week around Dundee.

The local newspapers began to carry occasional accounts of her exploits but there was no “Eureka” moment when she burst into the spotlight. Quite the opposite.

‘I knew I needed to get better, so I did’

As she recalled: “I wasn’t good enough at an early age and I suppose I was a bit of a late developer. I was okay, but I wasn’t at the top of my group (at Hawkhill Harriers).

“When I was 14 or 15, I was winning local races and I was in the team if it was a biggish team.

“I was always there or thereabouts but not right up there. I needed to improve.”

So she pushed her body through the wringer, became renowned for organising training sessions that pushed her to the limit and gradually, inexorably, passed then surpassed her rivals on the domestic stage.

Eventually, she feared nobody and that was evident when she competed in the 10,000m at the Games in the Scottish capital 35 years ago. She was just 22.

McColgan soaked up the atmosphere and has never forgotten the tidal wave of emotion that enveloped her when she stood on the gold medal podium in Edinburgh.

Two friends had struck a wager with her that she would cry during the ceremony. She insisted that she wouldn’t. But when the anthem started playing and the arena was enveloped by a rapturous ovation from the packed crowd inside Meadowbank Stadium, even the gritty, unsentimental Scot was overcome and the tears flowed.

As she recalled: “I didn’t think I would, but the response of the crowd was something else and Scotland the Brave sounded so wonderful.

“It was so overwhelming, totally unbelievable. I could never, ever relive that moment.”

All the pressure was on McColgan

A burden of expectations had been heaped on her shoulders when several fancied Scots struggled to pursue an elusive gold medal in their homeland. One by one, they ran, and one by one, they faltered… but not the gallus Dundonian.

She stated: “There was a lot of pressure on me because it was the last opportunity for a gold medal for Scotland in track and field.

“I remember being in the hall of residence and Tom McKean ran the 800m and didn’t win, then Yvonne Murray didn’t win and both had been favourites to gain the gold.

“As I left to go to the track, the team manager turned and said to me: ‘Liz, you are our last hope’, which was the last thing that I needed to hear.

“But it was amazing, being Scottish and running in these Edinburgh Games. The support was electrifying and they were all willing you on.

“I was very confident of winning and felt really strong throughout my 25 laps, but every lap that passed, you could sense the spectators realising this might be the gold and it got louder and louder as the race went on.

“I knew from 1,000m out that I had won, so I had two and a half laps of soaking up the atmosphere.

“It never felt the same in any other championship in which I competed – that feeling of everyone in the stadium wanting you to win.

”It was a huge thing and it really set up my career path. For the Games, I purposely worked on doing more miles and longer preps and that was specifically aimed at being at my best in the 10,ooom. Thankfully, it all came together.”

The victory was the catalyst for McColgan to graduate to the highest level. But it simply increased her desire to improve her times, chase new targets, and disregard any thoughts of the loneliness of the long distance runner.

This was in a period where athletics was blighted by regular drugs scandals, political squabbles and Games boycotts, but day in, day out, she ignored anything superfluous and settled into the task of reaching the standards of which she knew she was capable.

She realised she wasn’t naturally gifted, but possessed one vital ingredient that propelled her ambitions: the ability to go where others couldn’t follow.

‘I knew I had to work for any success’

She explained: “When someone is naturally talented, it is easy to give up because they never really have to work that hard, but you get to a level where talent is not going to be enough and that is when you have to start working. And I mean really working.

“That’s when other runners around me started dropping out. They weren’t used to having to work for it. But I was and that spurred me on.

“I’ve always said that I wasn’t the most talented runner but I had to work really hard from day one.”

There were no days off or diversions in her schedule. Even Christmas Day celebrations with her family were interrupted by two gruelling runs, come hail or high water.

“Throughout the rest of the year, her training programme included 10-mile runs before breakfast, and a series of punishing track sessions, circuits and more running.

McColgan was a tough taskmaster, her own harshest critic if she felt she had failed to achieve her objectives.

At the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, she put in what was described by most commentators – and certainly the likes of the BBC’s David Coleman – as a terrific display when she tackled the globe’s leading luminaries.

It led to her standing on another podium but she “only” had a silver medal for company.

It didn’t matter that she had been involved in one of the best Olympic tussles with Russian Olga Bondarenko, who eventually burst clear in the last few seconds.

For her, at the time, anyway, second best meant second rate and she was so disappointed that she chucked her medal in a cupboard after returning home.

‘I never looked at my medal for 16 years’

She said: “Seoul really upset me, to the extent that I never even looked at my medal. It was just forgotten about. I just felt that I had let everybody down.

“And that lasted until the Athens Olympics (in 2004) when Paula Radcliffe had her bad run (in the marathon).

“I remember she was sitting in the street and she was crying. Her distress made me realise that I had got a silver medal and I was complaining about it.

“I then went and got my medal – and it was actually the first time that even my daughter (Eilish, who is herself an Olympic athlete) had seen it.”

There was nothing to complain about in her performance on a sweltering night in Tokyo where McColgan was intent on leaving the rest of the world chasing shadows.

In the 10,000 metres final, which took place just 10 months after the birth of her daughter, Eilish, the Scot produced a magnificent display of dominant front running, which was described by former Olympic medallist-turned-TV-commentator Brendan Foster as the “greatest-ever performance by a British distance runner, man or woman”.

I was among the millions of viewers who was with her every step of the journey and there were never any concerns that McColgan might run out of steam.

She was immersed in her own little bubble, recording a series a blistering laps with metronomic precision, and she spoke at the finish as if she had just completed a gentle jog in the park. Unforgettable, in every way.

It was a win that brought her a litany of honours, including an MBE for services to sport and the prestigious BBC Sports Personality of the Year award.

McColgan now wishes she could have enjoyed these halcyon days a little more. But she was so committed to chasing new challenges there was little opportunity to step away from the rigorous demands of training she had set for herself.

As she said: “The Edinburgh Games were the perfect stepping stones to my future success at World and Olympic level.

“But I actually semi-retired before the 1990 Commonwealth Games (in New Zealand) because I was bit disillusioned with athletics when I got the silver in Seoul.

“So I had some time out from the sport and I only decided 12 weeks before the 1990 Games began to start training and have a go at retaining my title.

”I was lucky to win when I raced in Auckland, because I was not in my best shape.

“Looking back, it would have been a good thing to live in the moment a bit more, but at the time I was on a bit of a bandwagon.

“Runners at their peak have a very short time and I was very aware of that.

“I wanted to do as much as I could, so as soon as a race was over, I moved on to the next one.

“Winning in Tokyo in 1991 was like that. I never really thought about being world champion. I just focused on my next race and on running faster.”

30 years ago @Lizmccolgan won gold at the Tokyo 1991 World Athletics Championships over 10,000m

At #Tokyo2020, her daughter @EilishMccolgan is competing over 5000m and 10,000m. pic.twitter.com/ULVFBjRdwr

— World Athletics (@WorldAthletics) July 25, 2021

In the last three decades, I’ve met many of the biggest names in Scottish sport and many have impressed me with their tenacity, resilience and unalloyed talent.

But there are three individuals in particular who have left their own, unique stamp on the different pursuits in which they thrived.

Chris Hoy’s in there, of course, as is Andy Murray. But the third of the trio is Liz McColgan, the woman who wouldn’t even let childbirth get in the way.

After all, she was running less than a fortnight after the birth of Eilish – while she still had her stitches in. Nothing – nothing! – was halting this fast and furious woman.