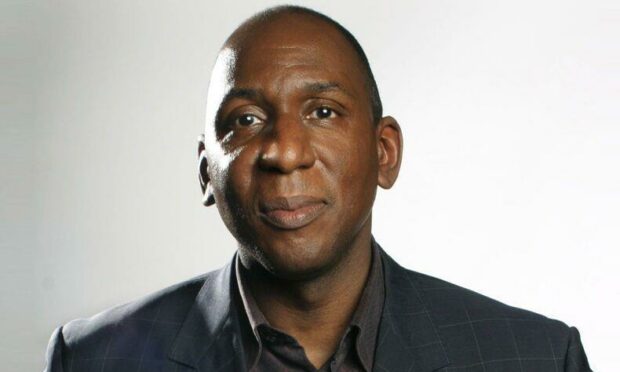

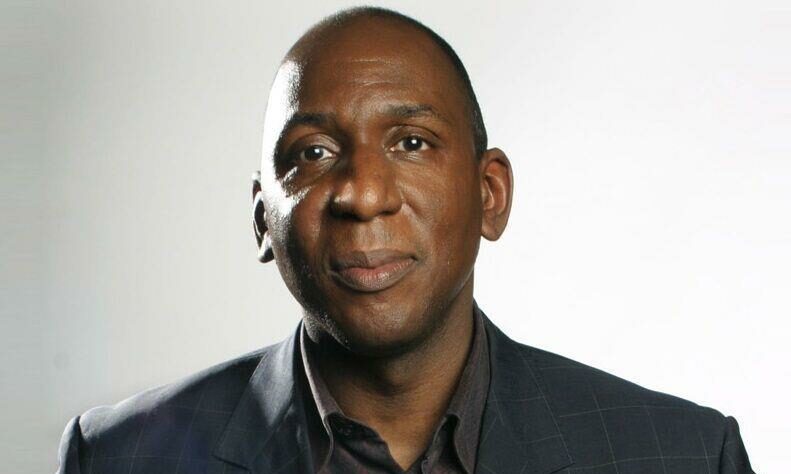

Actor and storyteller Colin McFarlane, who plays the slave Ulysses in Outlander, helped launch Findmypast’s new genealogical archive with a story about real life Scottish slave Scipio Kennedy – and revelations about his family’s own slave trade links. Michael Alexander reports.

He has spoken to school children across the country about his charity Making History, which inspires youngsters to discover something of interest in their family heritage.

But Colin McFarlane is also a master of his craft as an actor and storyteller.

He’s been in every staple of British television from Midsomer Murders and Dr Who to Bob the Builder and Dennis and Gnasher.

He’s best known for his role as Commissioner Loeb in the Christopher Nolan movies Batman Begins and Dark Knight, and probably most recognisable for his role as Ulysses the slave in the most iconic Scottish historical series ever produced Outlander.

When the 59-year-old London-born actor was tasked with being the final guest speaker at the launch of Findmypast’s vast new online collection of Old Parish Records recently, he acknowledged that there could be no role more relevant than that of Ulysses when talking about Scottish genealogy.

However, he also revealed a very personal story about his real-life Scottish connections, where fact and fiction have become increasingly inter-twined.

Very Scottish story

“You might know me from a number of roles across stage and screen,” he says.

“But none can be more relevant than the role of Ulysses – the character I portray in TV series Outlander.

“My Scottish connection continues with the fact I am now (the adopted) father to two Scottish children – a brother and sister. They lost their Scottish mum to cancer and sadly, their English father rejected them when they were about 15 and 12.

“I met them through my eldest son a year or so later and they have now been part of our family for about 11 years.

“The importance and impact of names, family and identity were underlined when my beautiful alabaster skinned ginger haired daughter surprised me just two years ago at Christmas where she decided to change her name by deed poll to McFarlane. I’m not ashamed to say it made me cry.

“Since we took her and her brother into our family, everything Scottish seems to come towards me.

“Securing the role of Ulysses in Outlander, set in Scotland with a Scottish story at its heart underlines all of that. I believe our identity and sense of belonging is crucial to us all.

“Yet personally, I can’t get beyond my own grandparents on my family tree which brings me to my family history story that I want to tell.”

Making History

Mr McFarlane explained how around 10 years ago, he was directing a play where a young black kid of about 14 discovers that the first person to the North Pole was a black man called Matthew Henson.

The teenager can’t believe it and when he finds out it’s true, it changes the whole way he looks at his life.

“I thought wouldn’t it be great if children of all ages, cultures, backgrounds could delve into their family and cultural history and be similarly inspired,” says Mr McFarlane, explaining that, from that seed, his Making History charity project was born.

The sharing of stories, unearthed by young people, has proved a great way to promote tolerance and understanding and give them a real sense of pride in who they are.

In terms of his own family tree, however, Mr McFarlane revealed that thanks to the newly released Findmypast parish records, he has also made his own remarkable discovery – a connection via his surname to a Scottish doctor on a Jamaican plantation.

“There was a rumour that there was a doctor in the family somewhere,” he says.

“We’ve now found that there was a Scottish doctor at a plantation in Montego Bay in Jamaica, where my father’s side of the family were from, and we found his name, information and where he was from.

🏴 Hm. It seems I could have Scottish roots! My 2 Scottish children would be most impressed! @Ancestry DNA tests have been ordered!!… https://t.co/IGo0RXbQzK

— Colin McFarlane (@colinmcfarlane) August 2, 2021

“All the slaves took their names from their owner, so I am related to this man, which is quite extraordinary.”

Outlander exclusive

Mr McFarlane excited Outlander fans by revealing that Go Tell The Bees that I Am Gone – the ninth and newest novel in the bestselling Outlander series – will feature a new character who is a freed slave called Scipio when it publishes in November.

This had been confirmed to him in a conversation he had with Outlander author Diana Gabaldon.

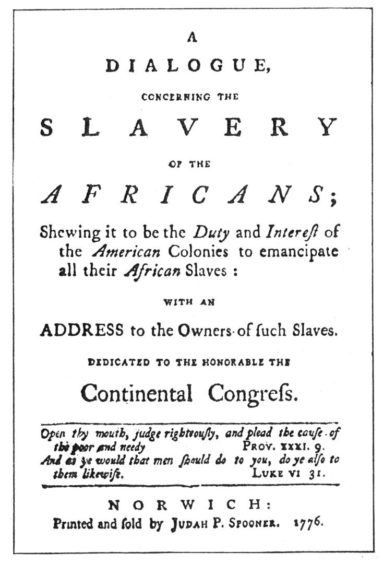

However, amongst the parish records now available online, it’s the story of real-life African slave Scipio Kennedy – who served as a slave in Scotland after being taken as a child from Guinea in 1700 – that Mr McFarlane, recognises as having synergies with his Outlander, and possibly even his own, family history.

“Scipio Kennedy was a man who had strong similarities to Ulysses, the man I play in Outlander, and he became a Scottish hero,” says McFarlane.

“Both were born freeman who were kidnapped and sold into slavery.

“Scipio’s Scottish story begins at Culzean Castle in Scotland. A story from the past that has tentacles reaching into the present.

“At the castle there’s a long list of names on the wall outside its kitchen. They are a list of some of the servants’ names who’ve worked there over the centuries. The first name listed is unlike all the others – it’s Scipio Kennedy.”

Scipio Kennedy story

The story of Scipio Kennedy begins in 1694 when he was born in West Africa.

His original name is not known. However, in 1700 aged five or six, he was captured in Guinea and sold into slavery. Much like Ulysses, from this point, his own cultural heritage was erased.”

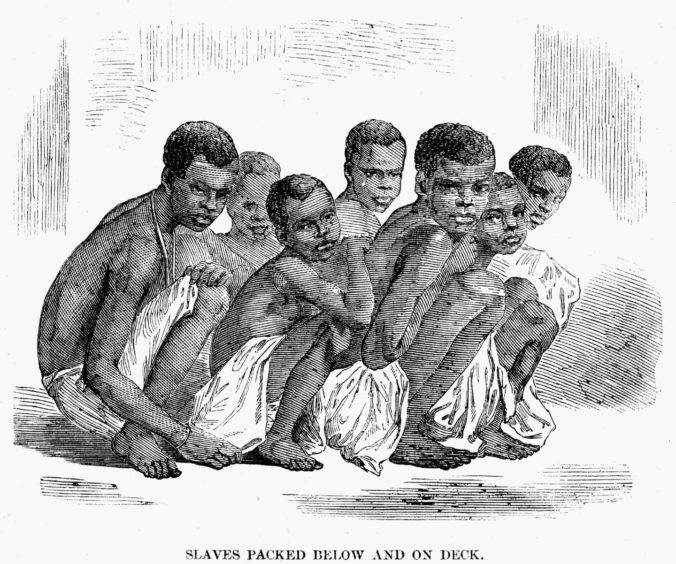

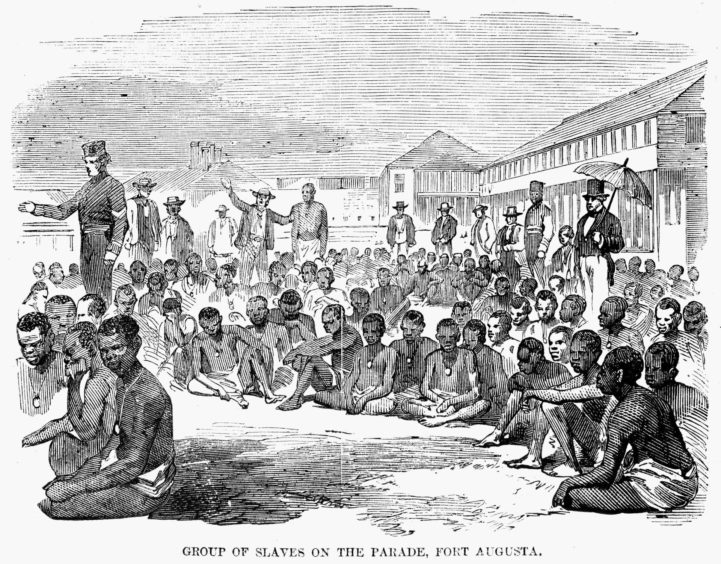

Kennedy was shipped to the Caribbean on a horrendous journey where up to 15% of slaves regularly died.

However, his story does not end in the sugar plantations of the West Indies.

He was purchased by Captain Andrew Douglas of Mains, Dunbartonshire, and taken to Scotland where he arrived as an eight year old in around 1702.

It’s likely that Captain Douglas purchased him to be a personal or household slave as young African page boys and footmen were viewed as “status symbols” in Britain at that time.

“The name Scipio is neither African or Scottish – it’s Latin,” explains Mr McFarlane.

“But it’s likely to have been given to him by Douglas at some point because it fits into a slave name tradition of the time, using the names of powerful leaders to mock the slaves’ powerlessness.

“In Scipio’s case he was probably named after the Roman general Scipio Africanus, conqueror of Hannibal and one of the greatest military strategists of all time.

“Although we don’t know much about Scipio’s life after being bought by Captain Douglas, we do know that he lived with him for about three years before moving with Douglas’ daughter Jean to a home in Edinburgh and then Ayrshire with her new husband Sir John Kennedy.

“It’s presumed that Scipio during these years in the Douglas home was Jean’s page.

“He probably worked in this role with Jean in various locations until 1710 when John inherited Culzean Castle and then moved there.”

Highly regarded

It’s known that Scipio served dutifully and was held in high regard. He was given an element of an education by the family and when Jean Kennedy the mistress he served for so long died in the 1750s, she left Scipio Kennedy, ‘my old servant’ the sum of £10 sterling – around the same amount of money she gave to each of her grand children.

It’s likely that Scipio was sign illiterate and couldn’t read or write extensively.

He could at least sign his own name, as evidenced by his signature on the contract that freed him from enslavement aged around 30 in 1725.

However, his signature seems painstakingly written and was misspelled.

Scipio supposedly now had the freedom to leave the employment of the Kennedy family.

The reality was, however, at a time when the Atlantic slave trade was still in full swing, and when he would have been viewed as a second class citizen, what else could he do?

“Even if Scipio felt maltreated by them and wanted to leave, as a lone African man in a rural Scottish community, his fate was likely to be at their mercy,” says McFarlane. “With no savings – because he’d never been paid – his new so called freedom would mean that his day to day reality changed very little.”

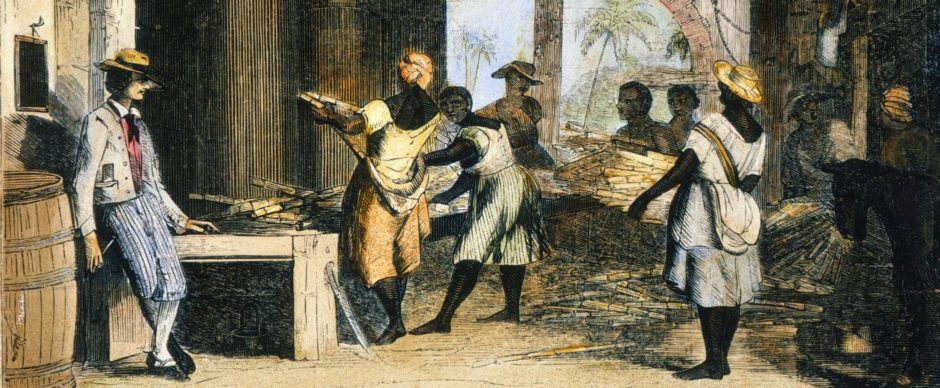

Scipio agreed to work for the Kennedys for at least another 19 years and was paid the sum of £12 Scots money yearly.

This salary was not unreasonable but it was still a very low wage as around £40 a year was needed to support a family. He’d go on to have eight children.

‘Fornication’

The Findmypast records show that in 1728, he was found guilty of “fornication” with a local girl named Margaret Gray. This was a scandal copied into the records of the Kirk Sessions.

Margaret had given birth to a daughter Elizabeth.

Scipio did the honourable thing and married Margaret. There seemed to be no discernible adverse reaction at the time to the fact that they were an inter-racial marriage.

“Race, as we conceptualise it today, is the social construct, largely to categorise people into groups based on physical characteristics, social relations etc,” adds Mr McFarlane.

“However, this was not a widely held view in 18th century Britain.

“Scottish philosopher David Hume wrote in 1722 when Scipio and Margaret had been married for about 14 years: ‘I’m apt to suspect the negroes and in general all the other species of men be naturally inferior to the whites’.”

The reality was black people had lived and worked and married in Britain for hundreds of years before Scipio and Margaret’s time, and incredibly for that era, Scipio lived to be 80 years old.

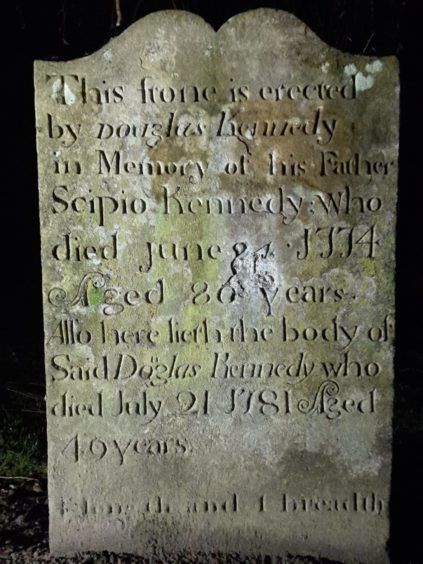

The money spent on his memorial by his son indicates the degree of love and affection the whole family held in him.

Mr McFarlane adds: “This Findmypast collection isn’t made up of the lords and ladies that swung around but the everyday folk who worked their fingers to the bone and made the modern Scotland we know today, and in some cases the modern world.

“Scipio Kennedy was a man born free, and although being born so many thousands of miles away, he became a Scotsman through and through.

“I’m so glad we can celebrate the fact that because of records like this in the collection, we ensure that so much more of Scottish history never dies.”

For more information on Findmypast go to findmypast.co.uk