Alistair Urquhart endured the brutality of a PoW camp, the horror of being held captive on a vessel that was torpedoed by his own side and was shipped to Nagasaki just weeks before an atomic bomb reduced the city to rubble.

No wonder his experiences during the Second World War in the Far East would have been dismissed as unbelievable by most Hollywood film-makers.

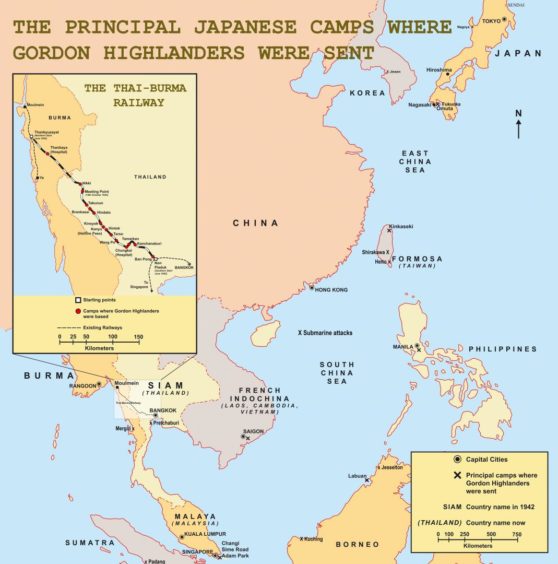

This was the young Aberdeen-born Gordon Highlander, who was among the tens of thousands of Allied troops taken prisoner by the Japanese after the Fall of Singapore, still regarded as one of the greatest catastrophes of the whole conflict.

This led to the deaths of thousands of young soldiers, the brutal incarceration of thousands more in prison camps whose commandants ignored the tenets of the Geneva Convention, and the period from 1941 to 1945 had a devastating impact on so many Scots whose ashes were scattered under the midnight sun.

When he left Scotland, at 20, he had been a fit and healthy man with an athletic gait, weighing in at 135 pounds.

Yet, six years later, he was a skeletal 82 pounds, he had been beaten repeatedly by his captors, had suffered from cholera, malaria, typhus and beriberi, and witnessed the deaths of so many of his colleagues.

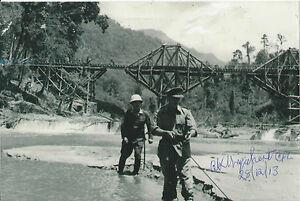

That was traumatic enough, but Mr Urquhart didn’t just spend two years as a slave labourer while helping to build the Death Railway in Burma and the bridge over the river Kwai, which was later turned into a famous film he regarded as “sanitised”.

Yet even he admitted that a truly accurate portrayal of what befell these unfortunate PoWs would have been too much for anybody to bear, let alone a generation that had been spared the privations of global conflict.

However, even in his 90s, and long after he had moved to Broughty Ferry, he remained determined that the facts about man’s inhumanity to man should never be forgotten while he and others from his regiment were still alive to preserve them for posterity.

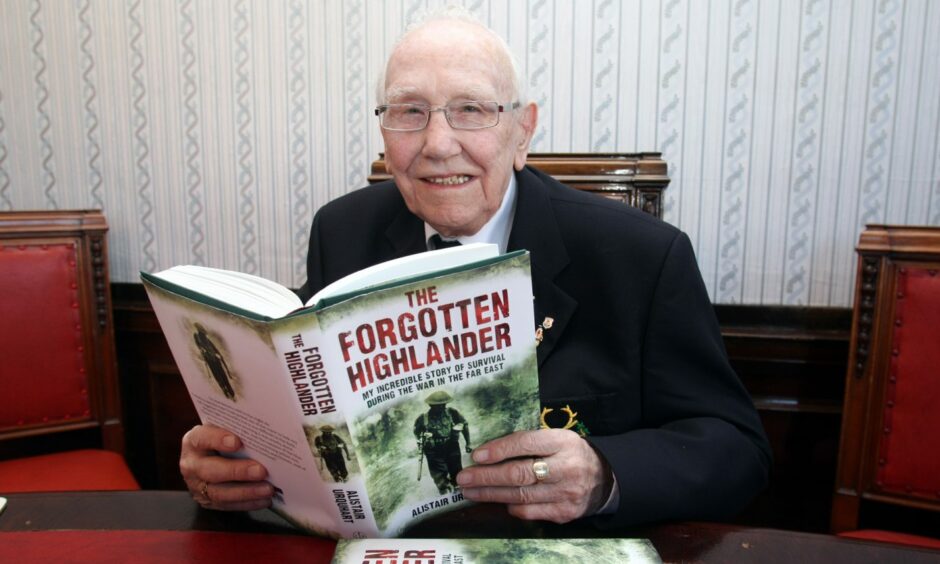

That was the catalyst for him to write a book – The Forgotten Highlander – at the age of 92 in 2011.

After it had been launched at the Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen, it proved to be such a compelling, often harrowing, but painfully truthful account of an extraordinary existence that it quickly became a best-seller.

Mr Urquhart’s travails seemed never-ending in the latter stages of the war. There was no respite from misery even after he had departed the detested concentration camps that had claimed the lives of so many of his confreres.

On the contrary, even as he was being shipped back to Japan from the jungle in the crowded, filthy squalor of a “hell ship”, the vessel was torpedoed by an American submarine, whose crew was unaware it was carrying many Allied troops.

He drifted, alone, for five days in the South China Sea, at the mercy of the elements before being picked up by a Japanese whaler and taken to Nagasaki, where he was used as forced labour in a shipyard, toiling for 14 and 15-hour shifts every single day.

The strain would have broken anybody. Eventually, it was too much for him and he was allowed to tend to the vegetable gardens of the Japanese army.

Trials and tribulations didn’t dispirit him

But yes, he was on the outskirts of the city when it was obliterated by the Allied deployment of a second atomic bomb on August 9 1945, just three days after the onset of the nuclear age had caused unprecedented devastation to Hiroshima.

He survived the blast but admitted it was a very different person who returned to the north of Scotland from the optimistic young lad who had left his homeland.

In common with his father, who had fought as a Gordon Highlander during the Battle of the Somme in the First World War, Mr Urquhart never spoke about his wartime privations for decades afterwards. The pain was too deep, the sadness too profound.

Yet his anger at the fashion in which the poor, beleaguered soldiers in the Far East were, in his view, airbrushed out of history eventually convinced him to open up about everything he had been through in his book.

He decided, right from the outset of the venture, that he would not gloss over any aspect of the campaign, not even the incompetence and complacency of some Allied commanders that sparked the fall of Singapore in the first place.

Unsurprisingly, his recollections were often grim, unpleasant and unsparingly honest. As he said of the fall of Singapore: “We stood there in the blazing sun, without food, water or shelter, and the horrible reality broke over me in sickening, depressing waves.

“I was part of Britain’s greatest-ever military disaster – just like some 120,000 others of us who were captured in the Battle of Malaya.

”I was a prisoner, and it was a gut-wrenching realisation to think that my liberty was gone and there was no telling for how long it would last.

“It was the worst moment of my life, but worse was to come in the years ahead.”

“I knew that people were dying around me on the railway, but I didn’t really want to know. It was all too dispiriting.

“It was difficult to judge the full toll of casualties and many of us became self-obsessed just to get through the day.

“One day at a time. That was all that you could keep in your mind.

”We all worked so hard at trying to survive that each person became more and more insular as it became more difficult. It required a superhuman effort to keep going.”

He watched wretched fellows succumb to different illnesses. In many cases, their immune systems were not equipped to deal with the conditions they faced. In others, the psychological torment reduced many of the prisoners to mere husks.

And, honest as ever, Mr Urquhart declared that his survival owed as much to such factors as luck or providence as any special qualities he possessed.

After his book became a success, he travelled to many speaking engagements and displayed remarkable vitality as he met families of those he had known 50 years earlier.

During his time on the Death Railway, he befriended the camp doctor, a Scot called Dr Mathieson who helped him through all his horrific ordeals.

Mr Urquhart had tremendous respect for his compatriot, which made a reunion at one of the book events all the more evocative and poignant.

Even as he talked to the throng who turned up at the session in Glasgow, there were two ladies prepared to wait patiently at the rear of an enormous book-signing queue.

Finally, they introduced themselves as the widow and daughter of his former comrade Dr Mathieson. And while Mr Urquhart was an old campaigner, who had grown inured to keeping his emotions to himself, he shed tears at the thought of the bonds which had been forged in the worst possible circumstances.

‘The happiness that will come’

But while he never forgave the Japanese troops for their failure to heed the Geneva Convention – and he remained critical, until his death in Dundee, at the age of 97 in 2016, about the lack of recognition accorded VJ Day by Allied countries – his story provided a reminder of the extraordinary resilience of many human beings.

On the one hand, he asked: “How does one describe the feelings of a person who has been through something like we had, something no one could ever have envisaged?

“They could never comprehend the depths of man’s inhumanity to man or the awfulness of an existence which consisted of surviving for one day at a time.”

And yet, as he surveyed his memories – in his 90s – this brave, indomitable fellow was still able to reach the conclusion: “Life is worth living and no matter what it throws at you, it is important to keep your eyes on the prize of the happiness that will come.

”Even when the Death Railway had reduced us to little more than animals, there was humanity in the shape of our saintly medical officers who triumphed over barbarism.”

Mr Urquhart’s final message to the younger generation was laced with positivity.

He declared: “Remember, that while it is always darkest before the dawn, perseverance pays off and the good times will return.”

They are words that still resonate five years after the Forgotten Highlander left us.