Jackie Sutherland grew up listening to her father’s remarkable stories of survival and courage in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp.

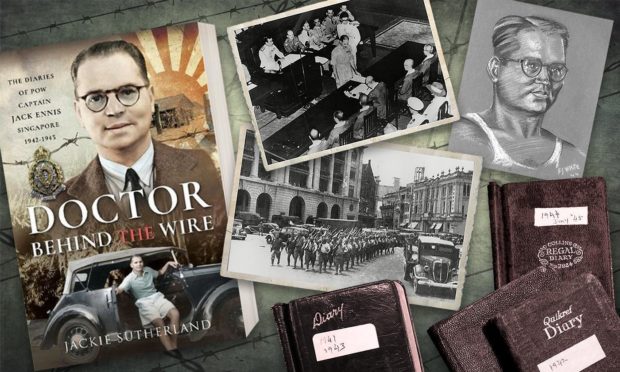

Captain Jack Ennis – an army doctor – kept a diary which he maintained during his time in captivity at Roberts Barracks from 1942-1945.

Jack’s diaries recorded the daily struggles against death, disease, injuries and malnutrition, and also the support and camaraderie of friends.

He died aged 96 in 2007 and the diaries were kept safe in a tin trunk before lockdown gave Jackie the opportunity to pull them together.

“Finally, the long hours of Covid lockdown gave me time to place these unique diaries in context – and write,” said Jackie, who lives in Milnathort.

“Just over a year ago I floated the idea of a book to a publisher, and to be honest, was astonished when the proposal was accepted within 24 hours.

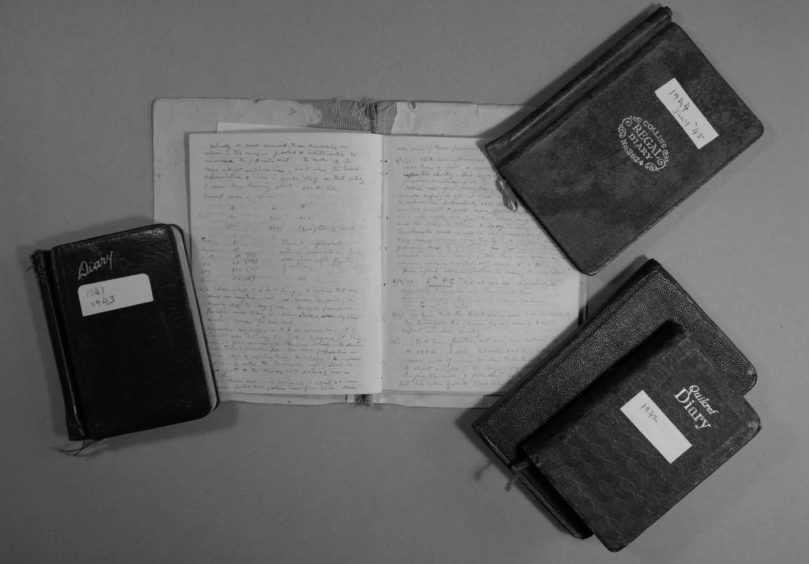

“Transcribing the diaries had taken several years – deciphering the tiny spidery handwriting dotted with medical terms, apothecary measures, and names of out-dated medical procedures had required the skills of good detective work plus the tenacity of solving cryptic crosswords and jigsaw puzzles.

“Now, in lockdown, I had time to piece everything together – the diaries, the postcards, the smuggled letters between prison camps, the letters from home and so much more.

“My father deserves his own story.

“Unique among all the records from Singapore 1942-1945, his diaries detail the life in captivity of a doctor whose specialisms were bacteriology and pathology.

“His skills were much in demand in the struggle to control diseases such as malaria and diphtheria, compounded by poor diet and vitamin deficiencies.

“This is his story, often in his own words from his diaries.”

Who was Jack Ennis?

Born in India, Jack Ennis completed his medical training in London.

In 1941 he had returned to Malaya as a pathologist.

While in charge of a remote upcountry hospital, he met a young Scottish nurse called Elizabeth Petrie.

Less than a year later, just four days before Singapore fell, they married.

Jack and Elizabeth dodged Japanese fighter plane bullets and took refuge in storm drains on the way to their wedding.

After only a few days, Jack and Elizabeth were interned for the duration of the war.

Jack was sent to Roberts Barracks with military personnel, whilst Elizabeth, along with some 3,000 civilians, would be ‘housed’ within Changi Gaol.

The couple were separated and after meeting for 30 minutes at Christmas 1942, they did not see each other again until September 1945.

To keep some of the young girls occupied and entertained, Elizabeth set up a Girl Guide company under the strict scrutiny of the guards – with many restrictions, including no saluting, and no National Anthem allowed.

Jackie said: “Throughout his life Jack had always kept a diary, and despite shortages of paper, pen or pencil, maintained his diaries during internment.

“As well as his diaries, he kept meticulous and detailed pathology records, a truly unique record of the support given to medical care in prison camp – the shortage of writing paper exemplified by some reports hand-written in a deposit book of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation!

“The diaries recorded the day-to-day trials of shortages of food and medical supplies, the difficulties with erratic water supply and electricity, lack of medical equipment, the rules and regulations imposed by the Japanese, the irritations of head counts and spot searches for radios and cameras.

“But there were lighter moments too.

“Entertainment was a most welcome distraction in the prison camp.

“Carpenters, craftsmen and artists with skills rarely used since they had enlisted, now built theatres and concert halls.

“Indeed by the time of one Christmas pantomime, one young actor as a ‘wonderful princess, very, very pretty girl’ received a bouquet of flowers after the show!”

Food became scarce

Husbands and wives were kept separated until the first Christmas in captivity when some were allowed to meet briefly.

Throughout captivity many POWs sought to supplement their diets by growing vegetables on small garden plots, and keeping hens or ducks.

As the latter became scarce, prisoners sought other sources of protein.

In a diary entry on July 3 1944, Jack wrote: “Caught a cat and had it stewed.

“I ate a portion after parade; it was excellent, white meat and very soft, awfully good …… what would Mother say!”

By early February 1945, disease and poor diet continued to take their toll.

As Jack wrote: ‘We talk of death now, not really fearing it except that if it should come it be quick, but my spirit would be intensely annoyed if, after lasting so long, I should die, and that seems to be the opinion of all in my room.’

Throughout their time in Changi and then Kranji camps, at great risk of discovery, prisoners had been kept informed by news from hidden radios.

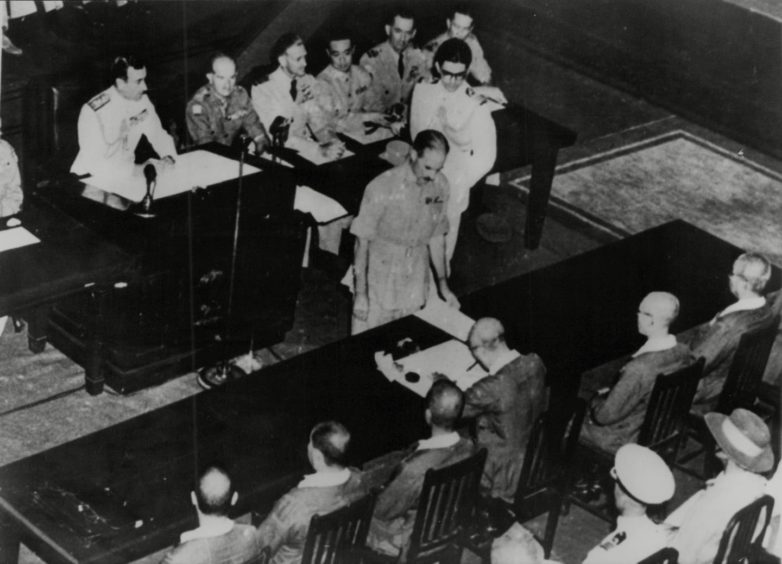

On August 9 1945, they heard of the dropping of the atomic bombs, and on August 15 the Emperor of Japan broadcast they had surrendered at noon.

Jack and Elizabeth were reunited and returned to Britain on the SS Monowai, which was the first ship to repatriate into Liverpool.

Hardship and deprivation

Post-war, Jack ran pathology services for the Durham Group of hospitals, also taking on forensic work throughout north-east England.

Jackie said: “In post-war years, Jack was often called upon as a speaker.

“Audiences appreciated his often humorous tales from prison camp – of keeping sea-snakes in an outside bath-tub and being asked if the snakes came down the tap, of racing frogs across the yard (only to discover the Australian team always won as they had managed to wire a small pin under each frog to make it jump further), of the mystery of the beans stolen from his garden (and then a couple of days later four soldiers being admitted to hospital with ‘food poisoning’).

“He told of his wildlife observations (the fruit bats and flying lizards around the prison huts), extremes of climate endured (heat, rainfall and thunderstorms) and quieter moments when admiring vivid sunsets and sparkling night skies.

“In contrast, Elizabeth rarely spoke of her days in captivity.

“Despite the years of hardship and deprivation, both my parents lived into their 90s.”

After retirement from the NHS he worked in Australia before finally retiring to Edinburgh.

Elizabeth continued her interest in the Girl Guides, becoming County Commissioner for North-east England.

She died in 2003 aged 93.

The book, ‘Doctor Behind the Wire’ was published this summer.

Jackie said: “It is a tribute to my late parents, Jack and Elizabeth Ennis, and to all those who were caught in the conflict in the Far East.

“On August 15 this year and as every year, many will pause just to remember the conflict and sacrifices made in the Far East.

“My parents were fortunate (they survived) and returned with mementos of their time in captivity – Jack’s diaries, smuggled letters (they were in different gaols), postcards home, an aluminium letter knife made from aircraft wreckage, home-made wooden sandals and much more.

“Items from this collection are currently on display in the Kinross (Marshall) Museum and can be viewed in the Campus Library.”

Doctor Behind the Wire, published by Pen & Sword, is on sale now.