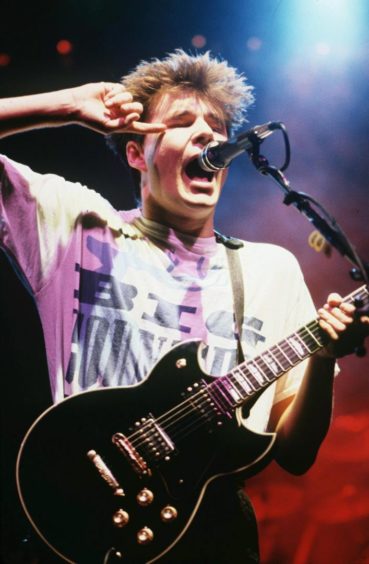

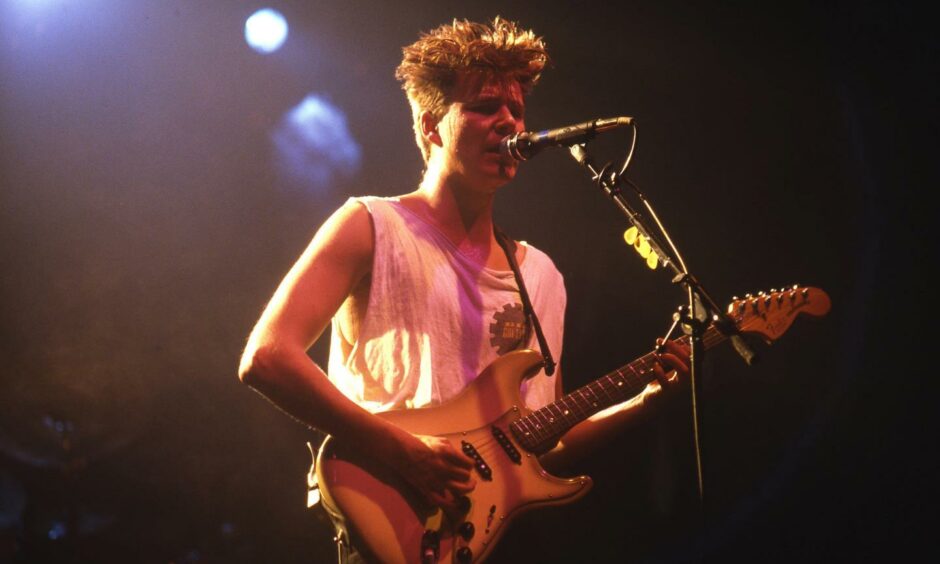

Stuart Adamson formed Big Country after The Skids split up in 1981.

But could the band have started out life as The Rodeo Giants?

The misguided moniker was among dozens of band names thrown around by Adamson after a practice session in a community centre in Dunfermline.

Adamson spoke about picking up his first guitar aged 11 and the band’s inception in a wide-ranging 1985 interview which was found in the DC Thomson vaults.

He said: “I left my previous group, The Skids, at the start of 1981 and began writing songs with a view to forming my own band.

“First, I approached Bruce Watson, because I’d been impressed when he played in a group with my wife’s brother.

“We practised in the local community centre and tried out several other local lads – but it just didn’t work.

“Then I remembered bassist Tony Butler and drummer Mark Brzezicki, who once played with the support band on a Skids tour.

“Right from the start they gelled perfectly with Bruce and myself.

“Back in that Dunfermline community centre, Bruce and I tossed around dozens of names.

“Most of them were plain daft – The Rodeo Giants is one I remember.

“Then I thought of Big Country.

“There was no reason, apart from the fact it seemed to go with the sound we were aiming at.

“Everybody else agreed, so the name stuck.”

Born in Manchester, Adamson grew up in the mining village of Crossgates in Fife.

The first guitar he picked up was his Uncle Drew’s who taught him a few chords.

Adamson’s father bought him an acoustic guitar for his 11th birthday and had a book called Hold Down A Chord which was part of the BBC2 tuition series.

He said: “From then on I only wanted to be a pop star.

“I’m completely self-taught.”

He wrote his first song aged 13 and formed a covers band called Tattoo at 14.

They used to rehearse in the local Miners’ Welfare Institute and started running discos every Friday to help pay for equipment.

Adamson would make more money by doing paraffin deliveries in Cowdenbeath and tattie picking for Crawford’s in Crossgates.

His first guitar cost £45.

The band started to play Rolling Stones and David Bowie covers in the local dance halls.

Bill Simpson joined on bass and the band started to play regularly at RAF bases and places like the Two Red Shoes Ballroom in Elgin for £30 a night.

Tattoo broke up when the lead guitarist left to join the Edinburgh police.

Adamson left Beath High School with eight O-levels and four Highers.

He planned to go to university to read English but thought he would be skint and have no money to buy equipment and pursue a music career.

He took a job with the council as a trainee environmental health officer but thought there was more to life than Crossgates and went to Amsterdam aged 18.

He realised it was just the same as home, turned around and came back.

Punk was happening.

Adamson and Simpson decided to form a punk band.

The band needed a singer with the right look and attitude and Adamson met Richard Jobson in 1977 who was a punk with black and white hair.

Jobson said: “I hear you’re starting a band.

“I’m looking for a band to be in.

“I can do great Lou Reed impersonations.”

The Skids debuted live in August 1977 having trialled their sound at the Fife town’s Kinema Ballroom where Adamson met his first wife Sandra.

Within six months they had released the Charles EP on the No Bad record label.

Fame came quickly over the next couple of years with Jobson/Adamson-penned classics including Into The Valley, The Saints Are Coming and Masquerade.

Adamson wanted to be his own man again and he left the band in 1981 after the recording of their third album The Absolute Game.

Sandra supported him, working as a telephonist, while he wrote songs and tried to get the band together which would become Big Country.

Hooking up with guitarist and long-time friend Bruce Watson, an early Big Country line-up also featured Clive Parker and brothers Pete and Alan Wishart.

They were soon replaced by bassist Tony Butler and drummer Mark Brzezicki.

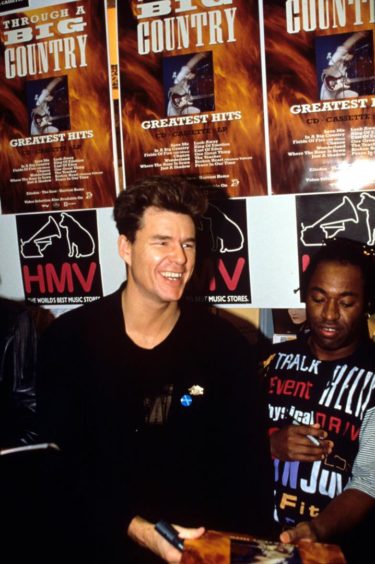

Signing to Polygram’s Mercury imprint, the band’s 1983 debut album The Crossing went on to sell more than two million copies worldwide.

Second album Steeltown went to number 1 in October 1984 and Adamson’s lyrics would articulate the plight of Britain’s embattled working class.

“I’m working-class, and proud of it,” he said.

“My upbringing instilled values in me that have never gone.

“They’re the reason I’ve been able to keep my feet on the ground.

“My family weren’t musical in the strictest sense, but Mum was keen on records of all kinds.

“Her folk and country tastes are echoed in the Big Country sound.”

He was asked in the 1985 interview why he didn’t leave Dunfermline and chase the bright lights following the success of The Crossing and Steeltown?

“Because I genuinely like the place,” he said.

“I still go for a pint with my old pals from school and every chance I get I’m on the terracing at East End Park cheering on the Pars.

“I’ve been a Dunfermline fanatic since being lifted over the turnstiles as a six year old.

“Apart from all that, I draw inspiration for lyrics from the people I’ve grown up with and know well.

“I’ve seen too many other musicians’ songs deteriorate when they get away from their roots.

“I decided from the start I wasn’t going to be a reclusive prima donna.

“So when folk see you every day in town they don’t think twice about whether you’re famous or not.”

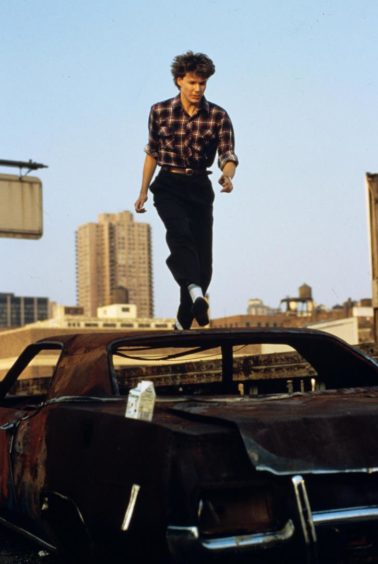

Adamson was also asked about success in America following two coast-to-coast tours including playing in New York eight times to big audiences.

He said: “Both our albums The Crossing and Steeltown have earned gold discs there.

“Two Hogmanays ago, our concert at Barrowland in Glasgow was beamed live all over America.

“Strangely enough success on the other side of the Atlantic isn’t particularly important to me, although the money’s nice.

“I’d have been happy just to have people here like our music.”

Adamson wrote some of the most poetic lyrics ever sung in a rock band.

“I like to boost what I believe to be basic good human values – honesty, the worth of the family and the community, and so on,” he said.

“My aim is to bring out the deeper feelings in a particular situation.

“Another idea I’m always striving to get across is that everybody has the potential to be good at something.

“A lot of youngsters these days, particularly in a high unemployment area like Fife, feel they’re useless and life is passing them by.”

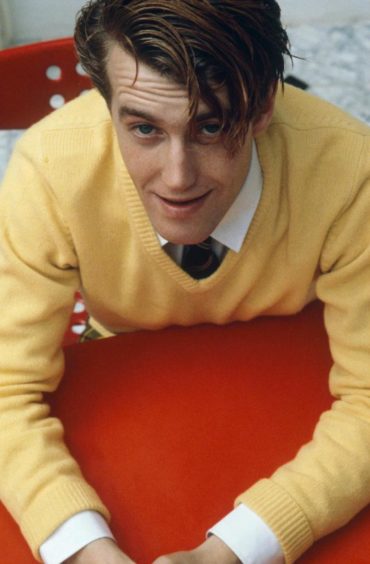

The 1985 interview finished with 27-year-old Adamson being asked how long he thought he would go on making music?

“Until I stop enjoying it, or until I feel I’m too old,” he said.

“I’d hate to end up like the Rolling Stones or The Who, who eventually became parodies of themselves.

“You look daft singing songs about rebellious youth in your forties.”

Mick Jagger must have missed Adamson’s 1985 interview from the Sunday Post because he invited Big Country to support the Rolling Stones in 1995.

Big Country were promoting seventh studio album Why The Long Face when the band landed the special guest slot on the Voodoo Lounge European tour.

In 1998 they were once again invited to open for the Stones on their Bridges To Babylon tour of Europe.

The Big Country album Driving to Damascus was released in 1999 before Adamson took his own life in Honolulu in 2001 at the age of 43.

Butler, Brzezicki and Watson reunited in 2007 to celebrate the band’s 25th anniversary.

They put the band back on the road in the summer of 2010 with Watson’s son, Jamie, joining on guitar, and Alarm singer Mike Peters asked to sing Adamson’s lyrics.

Further line-up changes happened when Butler retired and Peters left the group.

Now with singer Simon Hough and bassist Scott Whitley they are still filling venues from across Europe and Australia to hometown Dunfermline.

Big Country have always been the people’s band.

Adamson left behind an artistic legacy that continues to influence and inspire.

More like this:

Big Country guitarist was locked up inside Colditz after Rolling Stones gig

Unseen images of the Rolling Stones in Aberdeen in 1982 – in colour