Twenty years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Michael Alexander speaks to St Andrews University terrorism expert Dr Tim Wilson about the legacy of the attacks and renewed threats of terrorism in the future.

If Tim Wilson was looking for a distraction technique on the afternoon of Tuesday September 11, 2001, then turning on the TV turned out to be particularly effective.

Having left it late to write up his masters dissertation on comparative ethnic conflict at Queen’s University Belfast, he decided to take a 10 minute TV break to escape his notes and refresh a mind gripped by “massive panic”.

Yet when he turned on the TV, he was surprised to discover that every channel seemed to be showing what appeared to be the same “big-budget schlock disaster movie”.

Needless to say, no further words got written that day as the magnitude of the real life terror attacks unfolded.

But 20 years on, when Tim thinks back to the drama of 9/11, the now director of CSTPV (Handa Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence) at St Andrews University is struck by the “boundless nature of the day’s confusions”.

“What I remember really clearly is how open ended the chaos was,” he tells The Courier.

“No one knew what the hell was going to happen next. There was talk of car bombs going off, talk of 20,000 dead – things that were nonsense. But who could corroborate anything authoritative in the middle of that? It was just extraordinary!”

The attacks

History now records that on September 11, 2001, 19 militants associated with the Islamic extremist group al Qaeda hijacked four airplanes and carried out suicide attacks against targets in the United States.

Targeting the “signature structures” of American military and financial power, two of the planes were flown into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City and a third plane hit the Pentagon just outside Washington, D.C.

The fourth plane, United Airlines Flight 93 – possibly bound for the US Capitol dome, White House or Camp David – crashed in a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, after the heroic resistance of passengers.

Almost 3,000 people – including Angus man Derek Sword – were killed during the attacks, which triggered major U.S. initiatives – including the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq – to combat terrorism and defined the presidency of George W. Bush.

Yet despite the multiple targets, it’s the doomed Twin Towers that still dominate the iconography of 9/11.

Unplanned bonus

The crashing of the first American Airlines Boeing 767 into the north tower of the World Trade Centre at 8.46am New York time was captivating enough.

The impact of what was first seen as a possible freak accident, left a gaping, burning hole near the 90th floor of the 110-story skyscraper, instantly killing hundreds of people and trapping hundreds more in higher floors.

However, as emergency services responded and TV channels broadcast the images worldwide alongside the growing disbelief of watching New Yorkers, the slicing of the south tower by a second Boeing 767 17 minutes later brought home the spine-chilling realisation, and sense of panic, that America was under attack.

The dramatic collapse of the towers amid a sea of dust and smoke massively multiplied the casualties by thousands. It also heightened the tension as to what might happen next.

Yet according to Dr Wilson, the spectacle of the twin towers’ collapse was an unplanned bonus for the perpetrators – a choreography heightened by luck, where scale mattered.

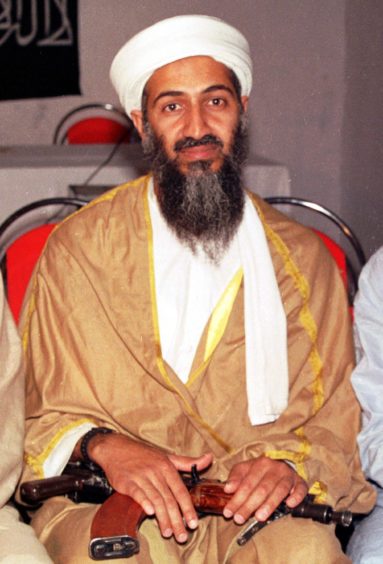

“It’s pretty clear from a recording we have of Osama Bin Laden talking to his mates a few weeks later that he didn’t expect the towers to fall,” says Dr Wilson.

“He actually thought it would just lop the tops of the towers off.

“As far as he was concerned, though, he was absolutely jubilant. It absolutely gave them the spectacle that they wanted.

“The fact it was central Manhattan, the fact the towers carried on standing for about an hour before they collapsed meant you had everything – the huge explosion and all the dramatic pictures of the planes first going in, then the tension of what the hell is going to happen next and a prolonged period of panic.

“It’s unusual for any terrorist attack to be so well documented.

Normally we see the aftermath. But here it combined the really mesmerising features of huge explosions and the atmosphere of a drawn out hostage crisis, watched live by millions.”

‘Sheer complacency’

Dr Wilson points out that the use of planes as weapons was nothing new.

As a child in the 1970s, he remembers hearing stories of Japanese kamikaze pilots in World War Two.

In 1972, hijackers had threatened to fly a plane into a nuclear reactor in Tennessee.

On Christmas Eve 1994, the Armed Islamic Group of Algeria (GIA), affiliated to al Qaeda – hijacked a plane in Algiers and, after murdering three passengers, planned to blow it up over the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

Their plan was thwarted when French controllers bluffed them to land at Marseille to refuel – only to be stormed by French special forces who killed all four hijackers.

“Perhaps with the exception of Guy Fawkes in 1605, the near misses just don’t get remembered,” says Dr Wilson.

The loss of 329 lives in the destruction of Air India Flight 182 by Canadian Sikh militants in 1985 (and another 270 in the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie just three years later) were reminders that planes can make effective terrorism vehicles.

However, without any note of anti-Americanism intended, Dr Wilson says the “sheer complacency” of America was “really striking” ahead of 9/11.

It was over 30 years since they’d had a multiple hijacking in US airspace and the threat didn’t seem to have registered widely enough with those in control of security at airports in the USA or more generally.

Not taken seriously

Dr Wilson says: “In the book Killing Strangers I wrote last year, there’s a very striking interview with the head of security at JFK, again about seven years before hand, saying ‘well the Middle East is too far away to threaten us here’.

“Again it’s extraordinary because they already knew that groups such as al Qaeda and affiliates had begun to turn their attention to the west.

“After all, in 1993 a huge truck bomb tried to fell one of the twin towers and killed six people.

“Looking back we say ‘well that was their first attempt and seven years later they got it right’.

“But it just wasn’t seen as the shape of the future at all. It was just seen as weird left over detritus from Afghanistan in the ‘80s.

“There were these odd Islamist groups, but we didn’t take them very seriously.

“The 9/11 Commission Report concludes that no one was looking for a foreign threat to domestic targets.

“The CIA were looking one way, the FBI were looking another way. There were plenty of straws in the wind – plenty chatter that had been picked up.

“But the US was still in this prism that this kind of terrorism wouldn’t touch its borders. It was something that happened to Americans in the Middle East or far away from America.”

Changed world after 9/11?

Despite the large scale drama of 9/11, deaths from terrorism were actually far higher in the 1970s, Dr Wilson explains.

An upsurge of “far left” terrorism and nationalist or “ethnic terrorism” involving the likes of Northern Ireland and Palestine helped build these peaks.

What’s striking, however, is the idea that 9/11 somehow marked a “break point” whereby the entire history of terrorism became obsolete.

British PM Tony Blair said his view of terrorism “changed in an instant” after 9/11 while US president George W Bush said “night fell on a different world”.

There was now an assumption from western policy makers that al Qaeda would and could get hold of Weapons of Mass Destruction.

Dr Wilson says the truth is that while Bin Laden was a “complete megalomaniac”, it’s clear WMDs were beyond al Qaeda’s capabilities.

The western doctrine of the pre-emptive attack that led to war in Iraq was increasingly “delusional”, he says, and it was clear even then that Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein had “precious little to do with al Qaeda”. The west’s response could even be regarded as a “tragedy in itself”.

One estimate seen by Dr Wilson in 2018 suggests that the “9/11 wars” – Afghanistan, Iraq and related conflicts like Somalia – have led to a death toll of 500,000.

Dr Wilson adds: “It’s not the Americans that have killed all those of course.

“However, even just looking at the pictures of Bagram Air Base the other day where we know torture was carried out (by the Americans), it’s a pretty sorry legacy.

“It so often underlines the point that very often the real danger from terrorism is not what anti-state actors can pull off – spectacular as the likes of 9/11 was – but the over-reaction of massive and powerful and rich states. That’s a sobering lesson in the aftermath on the Afghan debacle.”

Aberration of 9/11

Looking back, Dr Wilson says that in some ways 9/11 was an “aberration” – a “one trick pony that could not be repeated”.

Even on the day, it couldn’t be pulled off more than three times in a row once passengers on United Airlines Flight 93 learned of their fate and rose up.

However, it wasn’t a precursor of future trends.

From Islamic State inspired lone wolf stabbings to trucks ploughing down busy streets, the trend in terrorism since has been towards actions that are much more chaotic, much more spontaneous – and in some ways harder to predict.

“It’s not that the terrorism itself has become more destructive but it has succeeded I think in creating general unease,” he says, adding that the dystopian atmosphere of recent years is fuelled by camera phones waiting to record every incident.

At the end of the day, governments remain far more powerful than terrorists. It’s governments, after all, who recently shut us down with lockdowns.

However, Dr Wilson says there’s an inevitability that the west’s departure from Afghanistan will lead to a renewed terrorism threat.

‘Victory’ for jihadists

The manner of the American withdrawal will be taken as a “resounding victory” for jihadists over the world’s most powerful country and that will embolden al Qaeda and groups like it.

What remains uncertain, is the complexity of their relationship with the Taliban and “how tight a leash” they are on.

“The Taliban is not going to be as indulgent of al Qaeda as they were 20 years ago,” he says.

“Don’t forget Bin Laden effectively sprung 9/11 on the Taliban – he hadn’t told them it was coming.

“You can imagine there were some tensions in that alliance!

“Al Qaeda are not the organisation they were 20 years ago. They have lost all of their senior leadership.

“Whether they have the appetite for another round is debatable. It’s certainly more possible to imagine splinter groups.

“But there is Isis K who are clearly opponents of the Taliban leadership. For them this has just been the gift that just keeps giving.

“They’ve had the chance to position themselves as the more radical alternative to other jihadist groups, a massive amount of free publicity and I imagine that will have boosted their recruitment.

“Now, quite what their international range and reach and capabilities are we’ll have to see, but it’s obviously in their interests to keep the pot boiling – both in Afghanistan and internationally.

“That doesn’t mean they are in any position to pull off anything spectacular like another 9/11 – I don’t think that will necessarily happen.

“But for America declaring it’s all over while in the same breath saying that you are going to maintain over the horizon capabilities to strike Isis K wherever they are – it’s kind of hard to see how you square those two declarations.”