Dundee looked very different when trams ruled the roads and kept the city running for almost eight decades.

Dundee and District Tramways’ horse-drawn vehicles were launched in 1877.

Horse trams had to be small and light enough to be pulled with a full complement of passengers and seating capacity was generally limited to between 20 and 30, even on double-deck cars.

Even then, additional horses were normally required for any hilly sections of track while steeper gradients were normally ruled out altogether.

Most of the trams were made by Birkenhead firm of Milnes, although there was a local coachbuilder in Small’s Wynd.

Less than 10 years later the trams were steam and by the end of 1902 electricity was king, having killed-off an ill-fated experiment with uncomfortable trolley-buses.

Over the decades, the tram routes were extended in line with the expansion of the city and the peak of the network was in the 1930s, when 79 tramways were in operation.

The trams were all double-decked, four-wheeled and painted in a green and cream livery and the lines reached as far as Broughty Ferry and Monifieth.

According to a six-penny booklet published in 1936, the town’s trams were “lovely electrically-driven and electrically lit cars de luxe which we can now enjoy with so ample accommodation both inside and on the saloon on top, where one can smoke in comfort”.

All the way through two world wars the trams took people to work, to the shops, to the football.

The trams used to be packed to the gunnels.

You had people standing and hanging off the end.

The trams used to have a little box for uncollected fares.

The Lochee tram route was one of the most interesting, partly because it was so hilly, and partly because of the characters who either travelled the route or drove the trams.

That route, from Reform Street, via Ward Road and Lochee Road to Lochee High Street, was two miles long.

Drivers were allowed 18 minutes to get there and 14 minutes back.

Late at night, though, when there were no inspectors around, some of the drivers let rip and speeds of 45 miles an hour opposite Dudhope Park were achieved.

One of the drivers was nicknamed the Flying Scotsman!

The Dundee Corporation Tramways didn’t let them deteriorate like other companies did and they kept the fleet going well into the 1950s.

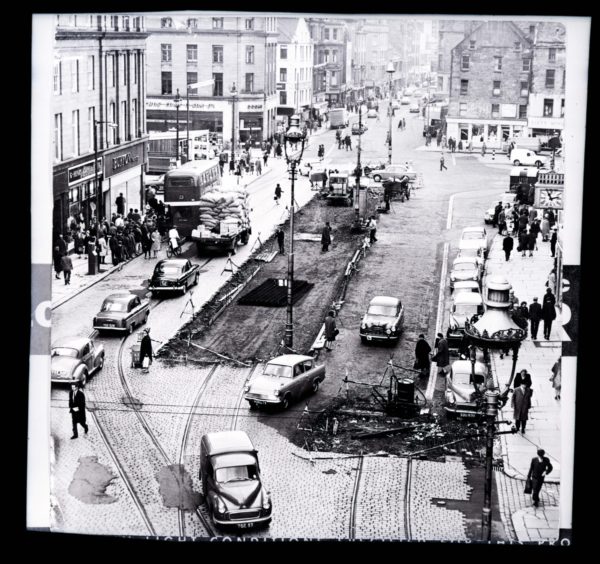

But by then they were starting to get old and their network of lines had been outgrown by the developing city.

A study led by transport consultant Colonel R McCreary showed the cost of trams compared with the bus service was 26.700 and 21.204 pence per mile, respectively and that 95% of daily passengers preferred buses.

As a result, he advocated abandoning the tramway system.

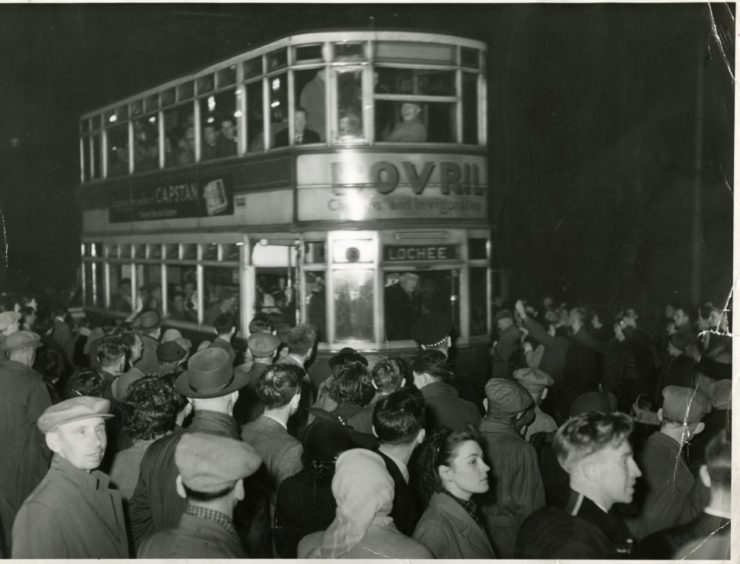

The last tram ran from Maryfield to Lochee in October 1956.

It was supposed to set off from the city centre before midnight, but it was delayed by over an hour on the way to Lochee by the crowds who turned out to see it.

More than 5,000 people witnessed Car No 23’s final journey, accompanied by the moving strains of We’re No Awa’ Tae Bide Awa’ and Will Ye No Come Back Again.

Armed with little more than the occasional penknife, they ripped, tore, tugged and hewed the interior of the tram in their frenzied quest for a souvenir.

You could hardly call them vandals, though, for no sooner had the trams completed their last runs than they were piled up and burned, without tears or ceremony, in a field at Marchbanks.

In fact, you could say that were it not for these highly-motivated asset-strippers, there would be even less around today to remind us of the days of the tram.

Driver David Bates was more philosophical: “Ah well, that’s that.

“Ready to start in the bus driving school in the morning.”

Could they ever return?

Proposals to bring trams back to the streets of Dundee as part of the £1 billion waterfront project were put before council chiefs in 2003.

However, then city development director Mike Galloway rubbished the plans, stressing Dundee’s compact city centre was already well served by bus networks.

Nostalgia about trams may have grown over the years, but it’s unlikely they will ever be seen anywhere now but the city’s transport museum.