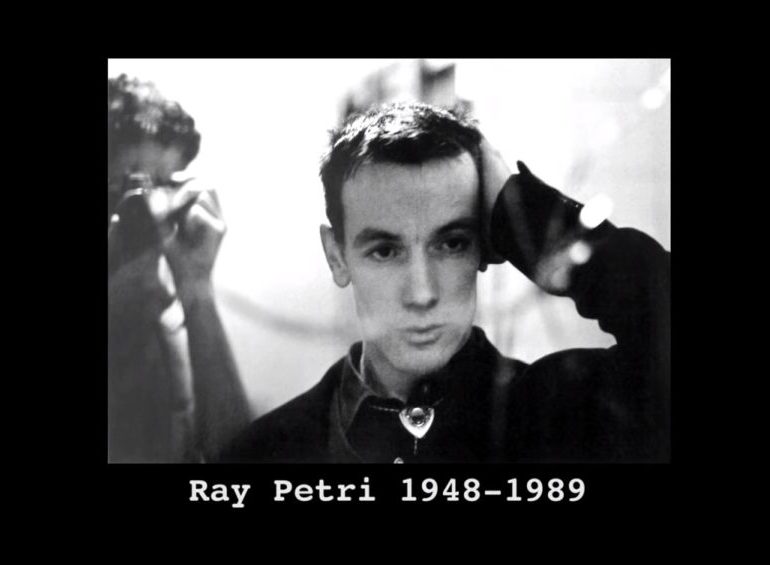

“Ray Petri changed the face of menswear in the 1980s and was without question one of the world’s most influential image creators,” says Mary McGowne, founder of the Scottish Style Awards.

Born Ray Petrie – he later dropped the “e” from his name – on September 16 1948 in Dundee, the creative visionary was the brains behind the Buffalo movement, which blended genres to create a unique sense of style that is still relevant more than 30 years later.

Early years

In 1963, aged 15, Petri moved to Brisbane with his family where he spent a number of years involved in the music scene, performing in a band called The Chelsea Set.

Around six years later, feeling that Australia was “too provincial” he relocated to London, where he ran a jewellery stall at the Camden Street antiques market.

He travelled aimlessly through India on his journey back to the UK and, upon landing in London, took courses in art history and antique buying at Sotheby’s to hone his skills.

Petri would photograph in clubs and on the street, in addition to running his stall, and soon became a photographers’ agent representing Jamie Morgan and Cameron McVey – who would later become founding members of Buffalo alongside Petri.

It wasn’t long before Petri was introduced to Nick Logan, editor of pop culture and fashion magazine, The Face, who gave him the platform he needed to establish himself as one of the “greatest stylists” of his generation.

Buffalo

It is widely believed that Petri was the first person to be referred to as a fashion stylist, with Mary noting that the Buffalo style he pioneered – a unique combination of street style and high fashion rooted in youth club culture – remaining the defining look of that era.

“It was the antithesis to the mainstream looks of the time and stood for individuality, diversity and liberation,” Mary said.

Petri’s eclectic social circle, known as the Buffalo Collective, included musicians (Neneh Cherry, Culture Club and Soul II Soul), models (Naomi Campbell, Nick and Barry Kamen), designers (Jean Paul Gaultier and Yohji Yamamoto) and photographers (the aforementioned Jamie Morgan and Cameron McVey, as well as Mark Lebon).

The group were key in defining what was stylish during that period and, as Mary says, it is impossible to mention ’80s youth culture without referencing Buffalo – a Caribbean expression adopted by Petri to describe people who are “rude boys or rebels.”

“The disruptive and radical movement transformed the way that society absorbed fashion with a pioneering style that became one of the most influential of the decade,” she said.

“Through his seminal shoots in style bibles of the time including The Face, Arena, Blitz and i-D, Petri pushed the boundaries of convention.

“He cast diverse, mixed-race models long before the industry caught up and applied the culturally-rich influences of his travels, from Scotland through Africa and India, into a youth-charged fashion aesthetic.

“Ray Petri’s vision and talent generated a cult movement and his groundbreaking creativity can still be seen, and indeed celebrated, today; a fitting testament to one of Dundee’s greatest cultural figures.”

In the Fashion Anthropologist blog, Petri is described as “the creator of metrosexuality and initiator of the androgynous and post-gender conversation in fashion” and “the first to realise that street style was a power to be harnessed”.

Combining elements of street style with luxury garments, his aesthetic was a distinct one. He put men in skirts and women in bomber jackets. Models were presented as both sensual and tough.

A Guardian article published in 2000 said that Ray’s vision coincided with the very beginning of what has subsequently become the commercialisation and mass consumption of street style.

He, quite notably, brought the MA1 flight jacket into the public consciousness by pairing it with loose-fitting Levi’s jeans. Add a porkpie hat and a pair of brogues and you’ve got Petri’s signature personal look.

The most influential – and probably most successful – fashion image creator of the ’80s, his work celebrated culture and inspired people to forge their own identity.

In an interview with the New York Times, French photographer Jean-Baptiste Mondino, who collaborated with Petri on multiple projects, recalled his love of classic Italian tailoring “done in a Caribbean way”.

“Ray was obsessed with extra-long shirt sleeves, so he would cut them off at the shoulder and reattach them with big safety pins so that they stuck out under suit jackets,” Mondino said.

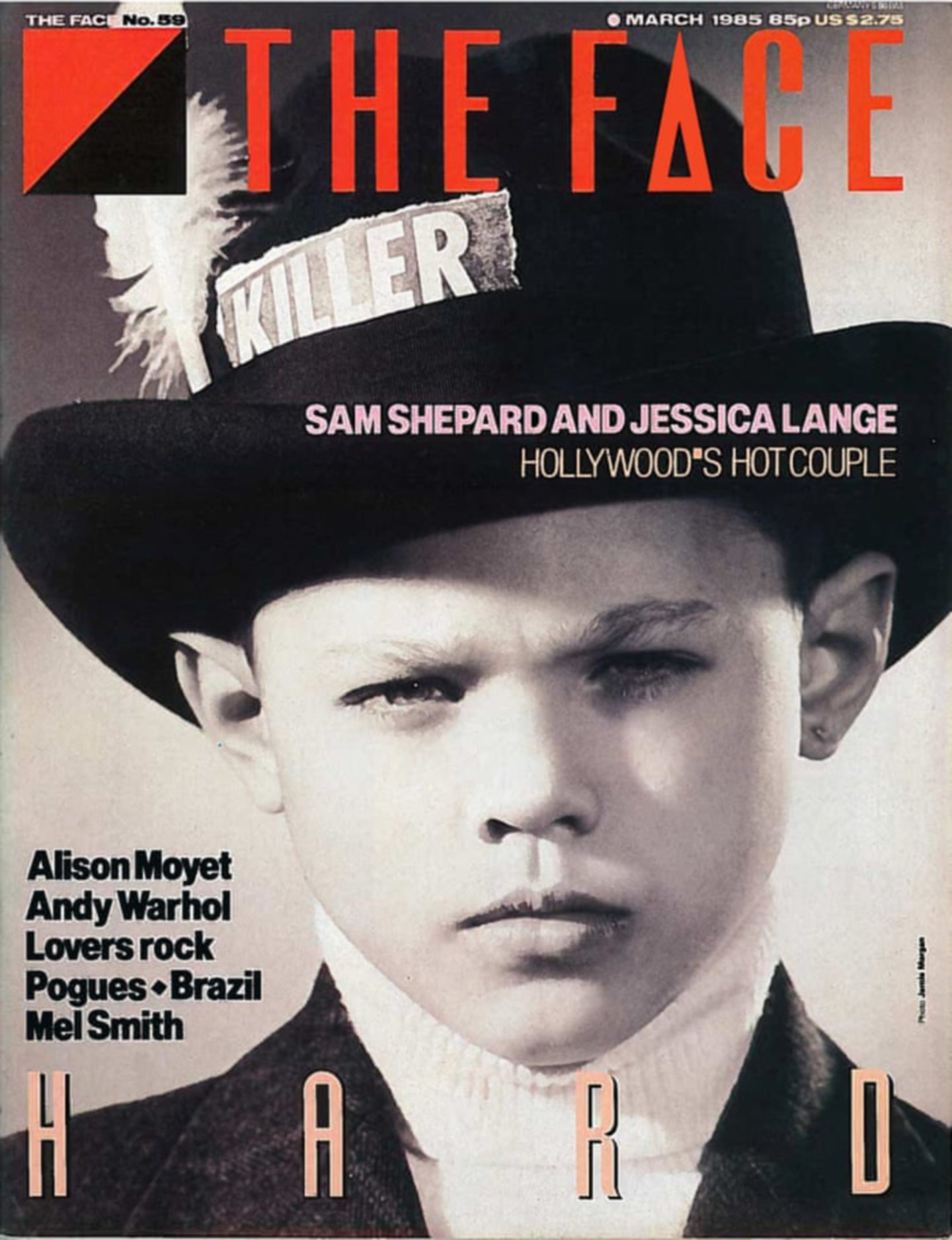

One of the most recognised images associated with the Buffalo collective featured on the cover of the March 1985 issue of The Face. Taken by Jamie Morgan, the photograph captures a scowling 13-year-old boy wearing men’s clothes, with the word “killer” emblazoned on his hat.

The provocative photograph was shot on 35mm black and white film and is seen as a rejection of the female-focused, soft and colourful photography that was happening in fashion magazines at that time.

For Barry Kamen, the image was about “taking gentleman’s hats and different sartorial influences and putting a Jamaican spin on it, then dressing these things on a young, 13-year-old Jewish boy”.

He said: “It was giving it a different spin, and then putting the headline on it, like the front page of a newspaper.”

Later years

In 1987, Petri developed what looked like a stye on his eye. This turned out to be Kaposi’s sarcoma – an AIDS-related tumour involving the skin and other organs – which would eventually spread all over his face and body.

Despite his illness he continued to work, although a lack of knowledge and understanding surrounding the disease meant that many did not know how to react to him.

Jean Paul Gaultier, who held a front-row seat for Petri until his death aged 41 in 1989, said: “I was actually criticised for that by people working in the business, which made me very upset.

“I felt that it was extremely courageous of Ray to expose himself. It was a show of strength, which I admired and had to support. But others refused to see the truth.”

Petri didn’t live long enough to enjoy financial or mainstream success from his work, but his legacy lives on.

From Helmut Lang and David Beckham – who once channelled Petri’s vision by wearing a patterned sarong over a pair of trousers during the 1998 World Cup in France – to the thousands of millennials whose urban style is based on a mix of sportswear and fashion, he was a man who left an indelible mark on the world.