There’s a stranger in Michael Schumacher’s house on Lake Geneva and he has been there for most of the last eight years.

His family still loves him, dotes on him, and are determined to maintain his dignity and preserve the stardust memories he created on so many different motor racing circuits throughout his glittering career in the fast lane of Formula One.

Yet they are dealing with the grievous consequences of Schumacher’s near-fatal skiing accident in the French Alps in 2013, which left him in a coma and fighting for his life.

A new Netflix film has just been released to tell his story from the glory days of champagne corks and championship drives – and occasional forays into Dick Dastardly territory – to the grim fashion in which he now exists in a sort of twilight reality.

His wife, Corinna, has been fiercely protective of his privacy at their home in Lake Geneva, but while the documentary strives to suggest there is hope for the future, the expression in her eyes betrays the transformation that has befallen the man who once revelled in the spotlight and ruthlessly repelled challengers to his global crown.

In his pomp, as the programme reveals, Schumacher wouldn’t accept anything less than 100% once he was behind a wheel, whether driving karts as a child, fitting old tyres to his vehicles which others had discarded and powering to victory in them, or advancing relentlessly through the ranks into the stratosphere of the Grand Prix circuit.

He was never interested in just dominating the sport for a year or two. On the contrary, he looked at the milestones achieved by Alain Prost and Ayrton Senna and committed himself to breaking them and surging to unprecedented success on the track.

Schumacher competed for 19 seasons in F1, between 1991 and 2012, winning 91 races, amassing seven world titles and suffered only one major injury during that period, a broken leg after a crash at the British GP in 1999.

Yet, like others from the elite motorsport sphere – including F1 icon Graham Hill, who perished in an air crash in 1975, and rallying world champion Colin McRae, who was killed in a helicopter tragedy in 2007 – the guardian angels who seemed to be protecting him in his car were powerless once he had climbed out of the cockpit for the last time.

Corinna does her best not to talk about her husband in the past tense. But she is clearly coping with an individual who is much changed from the man she married in 1995.

As she says: “Everybody misses Michael, but Michael is here, different, but here.

“We are together. Together at home. We do therapy. We do everything we can to make Michael better and to make sure he is comfortable.

“And to simply make him feel our family, our bond. And no matter what, I will do everything I can. We all will.

‘I never thought anything bad would happen’

“We are trying to carry on as a family, the way that Michael liked it and still does. And we are getting on with our lives.

“We had always made it through his races safely. I don’t know if it is just a kind of protective wall that you put up yourself or if it’s because you are, in a way, naive but it simply never occurred to me that anything could ever happen to Michael.”

One of the hardest aspects of the tragedy is how this once-vital, vibrant force of nature who was the toughest competitor in his pursuit has been rendered completely mute.

Because he wasn’t just a champion in the best car with better resources at his disposal than anybody else, but an indomitable character who arrived at Ferrari in the mid-1990s and discovered that the proud Italian company with the distinctive Prancing Horse emblem had been reduced to a shadow of its former self.

That was why he tore up the foundations, transformed the whole philosophy of the organisation and ensured that the tifosi – the passionate Italian racing fans who had been left shaking their heads in frustration at the team’s decline – could cheer again.

And he had already began orchestrating their route back to the summit when I met him at the British Grand Prix at Silverstone in 1998.

Even now, it was one of those special moments that remain indelibly etched in the mind.

And it happened on an overcast Thursday afternoon, with F1’s movers and shakers fine-tuning their machinery as the race loomed on the horizon.

We had initially arranged to meet Ferrari’s little coiled spring of ceaseless activity, Jean Todt, while he and his colleagues carried out their meticulous preparations with the attitude that genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains.

He was really funny, that’s what I saw in him.”

Corinna Schumacher

We watched and marvelled at their quest for perfection and the speed with which they functioned.

Todt was interesting enough in his own right. A 20th Century Napoleon commanding his troops while the fabled Ferrari organisation continued their rally from the doldrums of the mid-1990s, he spelled out his hopes and ambitions for the coming weekend.

The conversation was peppered with “Michael” this and “Michael” that and it was obvious that he regarded his leading driver with a combination of admiration and awe.

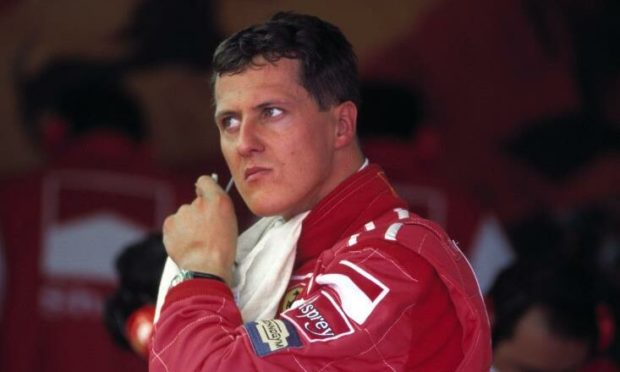

Then suddenly, Schumacher, wiry, steely-eyed, brisk and purposeful….a magnificent athlete in his prime, walked towards us and offered us the chance of a brief interview.

He was polite and pragmatic – “We think it might rain this weekend. That will change things” – penetrative and positive as he cast light on his expectations for the weekend. He oozed confidence, as well he might have done, given his myriad talents.

Todt looked at him like the Messiah

“We always have to focus on so many things and do whatever we can to give us an advantage. No matter how many times you win, you have to keep moving forward.”

Todt looked at him as if he was the Messiah, which considering how dramatically Schumacher had improved the fortunes of the Maranello organisation in the space of less than three years wasn’t that much of an exaggeration.

Indeed, in the next 72 hours, there was a fresh illustration of his mastery of the elements when the German prodigy, oblivious to appalling weather conditions during the main event on Sunday, performed as if he was in different class from his rivals.

Of course, he wasn’t without his faults or foibles and it wouldn’t do to depict him as some kind of saintly figure.

There were several instances where he lived up to his pantomime reputation as the villain of the track, whether in crashing into Damon Hill in 1994 or Jacques Villeneuve in 1997 during climactic races.

He detested losing and if there was a means, any means, of stopping an opponent, it was justified in his mind.

Yet, akin to the manner in which Senna took command of his pursuit until his untimely death at Imola in 1994, Schumacher was utterly uncompromising and unstoppable on his way to claiming five successive titles from 2000 onwards.

That period of supremacy couldn’t last forever but it established him as one of the greatest, if not the greatest-ever driver in Grand Prix history, a man equally adept in dry or wet conditions and whether leading from the front or pushing his rivals to the max.

Yes, he shouldn’t have emerged from retirement in 2010, and Schumacher subsequently struggled to gain the same adrenaline rush from anything outwith F1, whether in motorcycling or on the piste, but he stamped his imprint all over his milieu.

But it was never all about him. He knew the scale of the rebuilding programme that was required at Maranello 25 years ago and realised that it needed the whole organisation to buy into the belief that the Prancing Horse could dance again.

When I asked him about his role in reviving Ferrari, Schumacher responded: “I get all the glory, that’s just the way it is with these things, but I wouldn’t be going forward without all the people working hard behind the scenes every day.

“When I first arrived here, it was a bit like a museum. But I told everybody that hopefully, we can make our own history from now on and they did it.”

He faces an uncertain future with no guarantees of an improvement in his health.

But the new documentary, though not in the same league as the film Senna, highlights the love which Corinna and her son Mick (a rising F1 star) and daughter Gina, feel towards the warm, funny, compassionate and often vulnerable man, whose company they relished when he was away from the flashbulbs and TV hype.

In the end, and though he is only 52, Schumacher has nothing left to prove in sport.

How wonderful, but how unlikely, it would be if he won this bigger battle.

As Corinna says: “He’s simply the most lovable person I have ever met.

“He was really funny, that’s what I saw in him.”

There’s that past tense. And it’s heartbreaking.

- Schumacher is available now on Netflix.