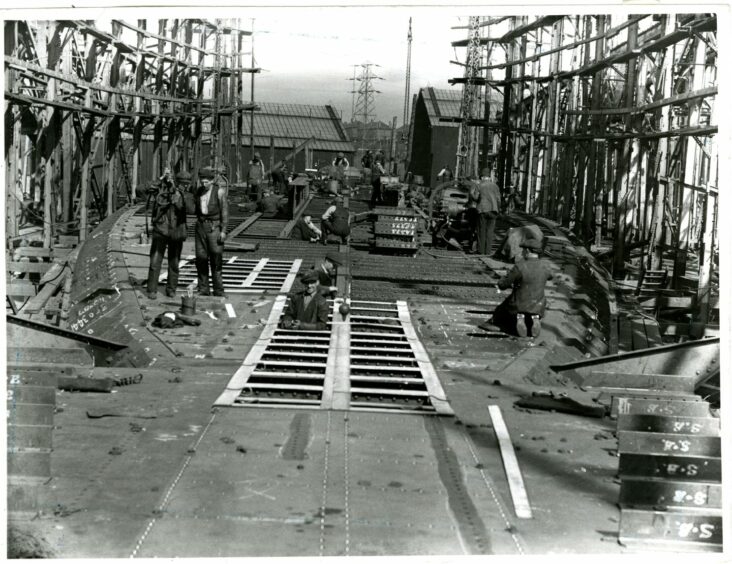

At its height it employed more than 4,000 workers directly, and up to 20,000 indirectly in support industries.

Alongside jute and jam, it was the manufacturing heartbeat of Dundee, an institution whose legacy reverberates today.

But it’s 40 years since the Caledon shipyard closed, and many still lament its passing.

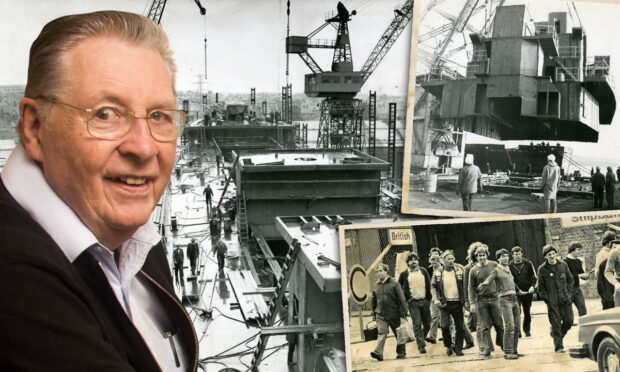

Jack Reilly spent 25 years in the shipyard working his way from apprentice to technical manager, including 16 years at the forefront of marketing and sales.

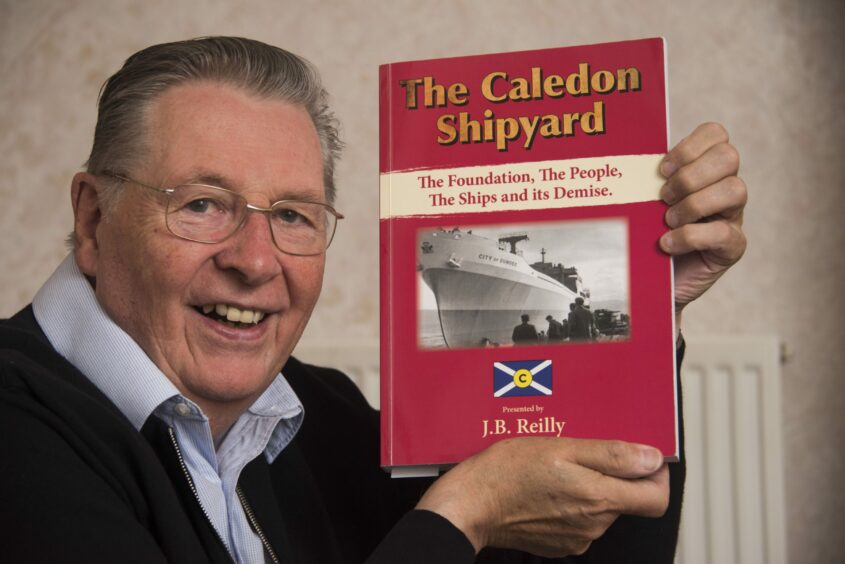

He has documented the yard, its ships, its people and its eventual demise in a 605-page tome that just keeps on growing.

The more Mr Reilly writes, the more people from all over the world contribute their knowledge and photographs of the shipyard’s history.

The book collates every ship ever built by the yard over its 107-year history, 1874-1981.

In its hey day in the 1930s the Caledon Shipyard employed 4,000 and another 2,000 at the Lilybank Engine Works in Kemback Street.

The shipyard was founded in 1874 by entrepreneur W B Thompson.

Beginnings in Stobswell

He had returned from a managerial post in a Finnish shipyard eight years earlier to set up an engineering business at the Tay Foundry at Stobswell about a mile from Dundee Docks.

In the five years prior to 1874, he had built four small yachts in his foundry and hauled them down to the river on bogies drawn by teams of horses.

His fifth vessel, the ‘Ilala’ was the first constructed at the new yard on Marine Parade, and on his own account.

Caledon, named after the Earl of Caledon, for whom the yard built an impressive screw steamer yacht Banshee, produced 556 ships in its 107 years.

From barques to barges, steamboats to schooners, passenger liners and cargo ships, many with photographs and drawings- Mr Reilly’s book, The Caledon Shipyard, The Foundation, The People, The Ships and Its Demise is a treasure trove of social and maritime history.

He describes all that is known about the ships’ histories including their different incarnations and owners, and their losses, some broken up or wrecked in inhospitable parts of the world, others victims of the two world wars.

Some ships gave long and valued service with vessels so popular it was “deadman’s shoes” before you could get a job working on them.

One, a four-masted barque named Lawhill gave service from 1892, survived two world wars and much derring-do before she was broken up in Africa in 1957.

Her loss prompted an outpouring from Dundee poet William McGonagall’s finest:

For 55 years she sailed the Seven Seas,

Going slowly when it was calm and faster when there was a breeze

During two wars she dodged the submarine and raider,

Proving a very great credit to the men who made ‘er.

The yard was also commissioned to build the girders for the second Tay Bridge.

Mr Reilly said: “It was a very difficult job to do as the girders weren’t flat but had a slight curvature.

“Accuracy was the biggest thing, and the internal painting was extremely stringent, there couldn’t be one spec of dust.

“The amount of steel Caledon used for the girders was the equivalent of four or five ships that the yard might have built.”

But the good days of hectic productivity didn’t last.

From the 1960s a perfect storm started to brew, when many Far Eastern countries started building ships and quoting prices only achieved by massive subsidies.

Containerisation was taking off, huge container ships putting paid to the service of many smaller vessels.

Mr Reilly said: “It also put many ports and shipyards situated in river sites unable to handle the large deep drafter vessels- therefore less contracts for shipyards like Caledon.”

Then came the European Economic Community which capped the shipbuilding output for the UK at about 50%.

British Shipbuilders, the nationalised company for shipyards capable of building ships of 3,000 tonnes, carried out EEC orders and closed the shipyards.

Caledon was the first to be forcibly closed.

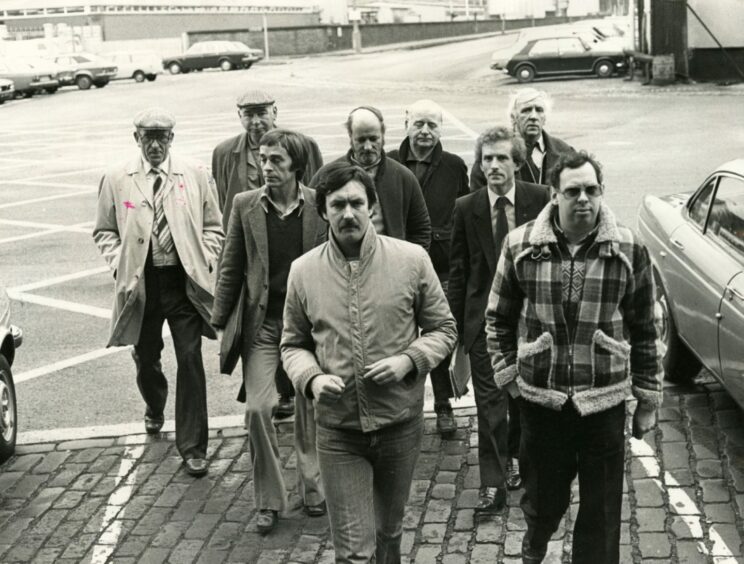

There were protests and sit-ins, shop stewards and union officials travelling to London to plead the yard’s case with British Shipbuilders.

Retired Caledon shipyard worker Henry Beveridge reflected on the closure many years later to The Courier.

He went into the yard as a 14-year-old in 1939 and was the last man standing when the city’s entire shipbuilding industry shut down in 1981.

As a determined union man he had battled in vain to keep the business afloat in the face of foreign competition before reluctantly throwing in the towel.

Everyone got up and left

“I just opened the door and said ‘there you go boys’,” he recalled.

“Everyone got up and left. I shut the door, locked it, went down to the lodge house and handed in the key and said ‘do what you like with it, we’re finished’.

“I never thought I was symbolically closing more than 100 years of Dundee shipbuilding.

“It never entered my head at the time. Only recently, when I read in The Courier about all the industries that have closed over the years, have I reflected on the significance of it all.”

Caledon was an easy first victim of the closures, Mr Reilly explains.

“The Caledon had no subsidiary companies unlike Scott Lithgow’s on the lower River Clyde, who were reported to have 200 subsidiaries including a funeral parlour, so Caledon was much easier to shut down.”

But more effort could have been put into saving Caledon, Mr Reilly is convinced, especially with the North Sea requiring offshore supply.

He did his own bit to generate income for the ailing yard.

Excellent technical people

“Within a week of the yard closure being announced I had 18 offers of employment.

“We had excellent technical people and all the shipyards were desperate to get them.

“I managed to secure contracts to keep 109 people employed for many years.

“But British Shipbuilders weren’t keen on doing anything for Caledon.”

Mr Reilly defends the Caledon from accusations of being a poor performer in its later years.

“It didn’t merit the bad gossip about it, words that sorrowfully can still be heard today.

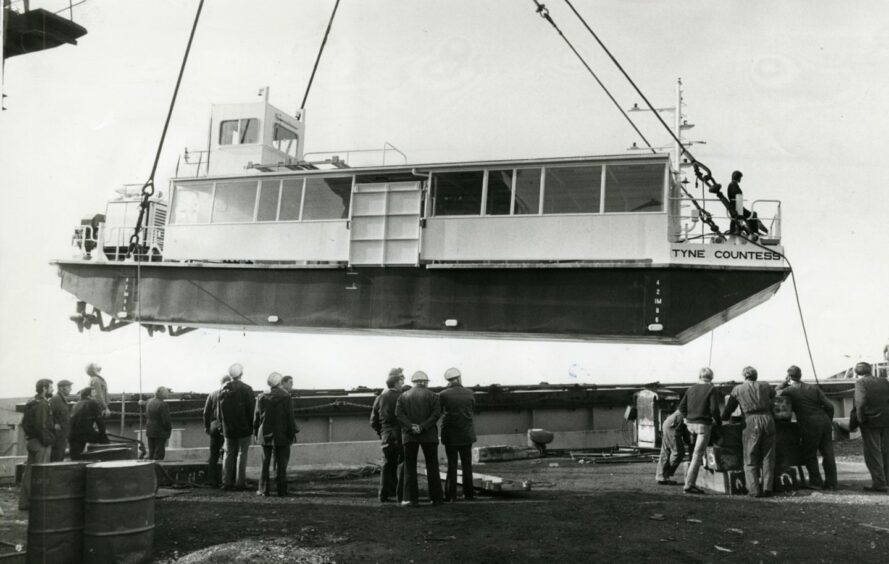

“The shipyard, in a closure situation, did deliver four export ocean-going ships on the order book at the time the announcement was given, also a small passenger ferry, Tyne Countess, for the River Tyne crossing service.

“The delivery date of these ships were however delayed by both work restrictions imposed by the workforce and by shortages of skilled labour by the company not retaining sufficient tradesmen to allow ship completions in a timely manner.”

Mr Reilly is a founder member of the Caledon Swim Club, started in 1968, based in the Gardyne College on Friday evenings.

It’s the only watery vestige of the Caledon that still continues.

Mr Reilly’s book is available through the McManus Galleries by contacting Paul Campbell on 01382 307214, email paul.campbell01@leisureandculturedundee.com

Mr Reilly is also happy to be contacted on 01382 456101.

You might also enjoy:

SS Californian: Dundee-built ship forever associated with the Titanic sinking

From skateboard protests to scenes at Timex: A history of demonstrations around Dundee

The man who closed the door on more than a century of Dundee shipbuilding