It was the “incredible chase” which sent excitement through Dundee and was immortalised by the world’s worst poet.

The 16.5-tonne, 40-foot long “great Tay Whale” was harpooned by Dundee sailors and chased to its end 45 miles up the Mearns coast in 1883.

Why was the whale in the Tay?

The young adult male humpback whale swam into the Firth of Tay after being attracted by an unusually large number of herring and sprat.

Many of the townsfolk came to watch it leaping out of the water, including adults who skived off of work and children who skipped school.

The wayward whale had little chance of getting out alive.

Dundee was the largest whaling port in Britain at the time and the entire fleet was laid up at home for the winter.

The trade was vital to Dundee, for jobs and industry, with oil used first primarily for lighting and then as a vital component in one of the city’s other major trades, jute.

After a few days the whalers decided to catch the whale to cash in on the potential cash bonanza that had appeared on their doorstep.

Whaling was more mortal combat than straightforward hunt and required some of the most dangerous, difficult and disgusting labour of any industry of the time.

A steam launch belonging to the Polar Star and two other whale boats succeeded in fixing harpoons to the animal but the whale swam out to sea, towing the boats after him as far as Montrose, even when the flotilla was joined by steam tug Iron King.

The whale’s decision to “twist about in all directions” snapped the lines.

The boats returned to harbour on New Year’s Day where a large crowd awaited and “much disappointment” was expressed.

However, on the morning of January 7, the whale was seen stricken off Bervie Brow by Alex Ritchie, skipper of the Gourdon fishing boat The Olive Branch.

Several of the men scrambled on to the whale and succeeded in getting a rope from each of the boats fastened around the tail.

Still further – to make sure of their prize – a chain from one of the boats was also attached and kept slack to be ready in case of any of the ropes giving way.

Winds prevented landing at Gourdon, and then Montrose.

They toiled all night to drag the weight but after 30 hours at sea, they saw the welcome sight of Dunnottar Castle and soon landed at Stonehaven Bay.

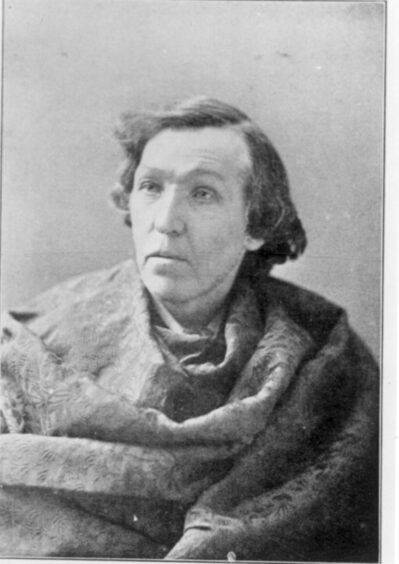

Sir John Struthers of Aberdeen University came down at low tide and took measurements and photographs.

Greasy Johnny

The fishermen who had landed it wasted no time in striking a deal with a canny fish merchant who paid around £150 for the Tay Whale.

Work began cleaning up the corpse for the following day’s auction where an oil merchant who was nicknamed ‘Greasy Johnny’ paid £226 for the catch.

John Woods was described as an enterprising Dundee merchant and a dealer in polar bears, Russian bears, seals, Arctic foxes and monkeys.

He bought wild animals from skippers off ships and kept them near his house in Roodyards Road which was close to the gasholders on Dock Street.

The whale was Greasy Johnny’s.

A full moon shone from the clear sky while a tug transported it back to Dundee where 2,000 people turned out to greet its return.

Its weight crushed two strong carts, before a heavy duty sledge, drawn by 20 horses, hauled the carcass to Woods’ yard.

It took 26 hours.

The Advertiser reported: “The fins and tail were white, and the glossy skin appeared beautiful in the moonlight.

“The whale will be exhibited in Mr Woods’ premises in East Dock Street for a few days.

“The operations were carried out with skill and coolness, and those who witnessed the strange scene will not soon forget it.

“It is stated that several scientific gentlemen from different parts of the country are anxious to secure the skeleton of this rare visitor to our latitudes, and that it is therefore doubtful where its bones may ultimately find their last resting place.”

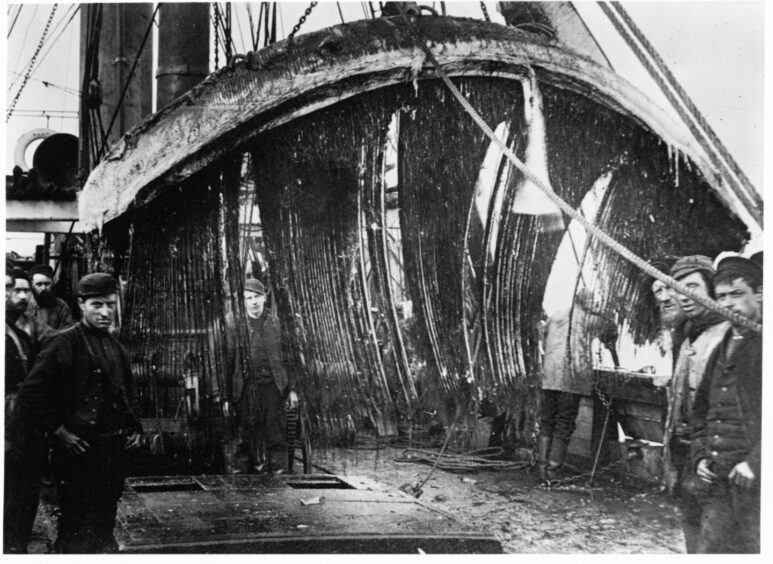

Woods commissioned commemorative photographs and put the dead animal on show in a gigantic tent next to Dundee flour mill in East Dock Street.

Somersaults on the whale’s back

Woods charged the public a shilling to see the whale in daytime and sixpence at night when the tent was lit by paraffin lamps.

Thousands were ferried from High Street to East Dock Street in buses to see the corpse and children skived school so they could see it.

On a single Sunday afternoon, 12,000 visitors paid to gawk.

Enthusiastic visitors even jumped on the whale’s back and did somersaults on it.

Three weeks later the Aberdeen Journal reported that with each passing day, the whale “became less attractive to the eyes, and especially to the noses, of its visitors”.

Dr Struthers arrived to dissect the decomposing remains.

He opened the animal with a massive incision working through skin, blubber, and viscera before removing its heart.

Greasy Johnny charged the public to watch the dissection and the band of the 1st Forfarshire Rifle Volunteers played while the scientists worked.

The remains were embalmed and the whale was reconstructed onto a wooden frame before visiting Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Liverpool, Manchester and London.

Several lorry loads of the flesh and bones were also packed up and consigned to Aberdeen University where Dr Struthers would prepare an articulated skeleton.

Greasy Johnny’s tour wound down in August 1884 and he donated the bones to the town of Dundee having more than recouped his initial £226 outlay.

Its skeleton is now housed in the McManus art gallery and museum.

The chase was immortalised by William McGonagall whose poem The Famous Tay Whale is just as well-known as his take on the Tay Rail Bridge disaster.

You may also like:

Why there was No Time to Die for James Bond writer Ian Fleming’s Dundee grandfather

SS Californian: Dundee-built ship forever associated with the Titanic sinking