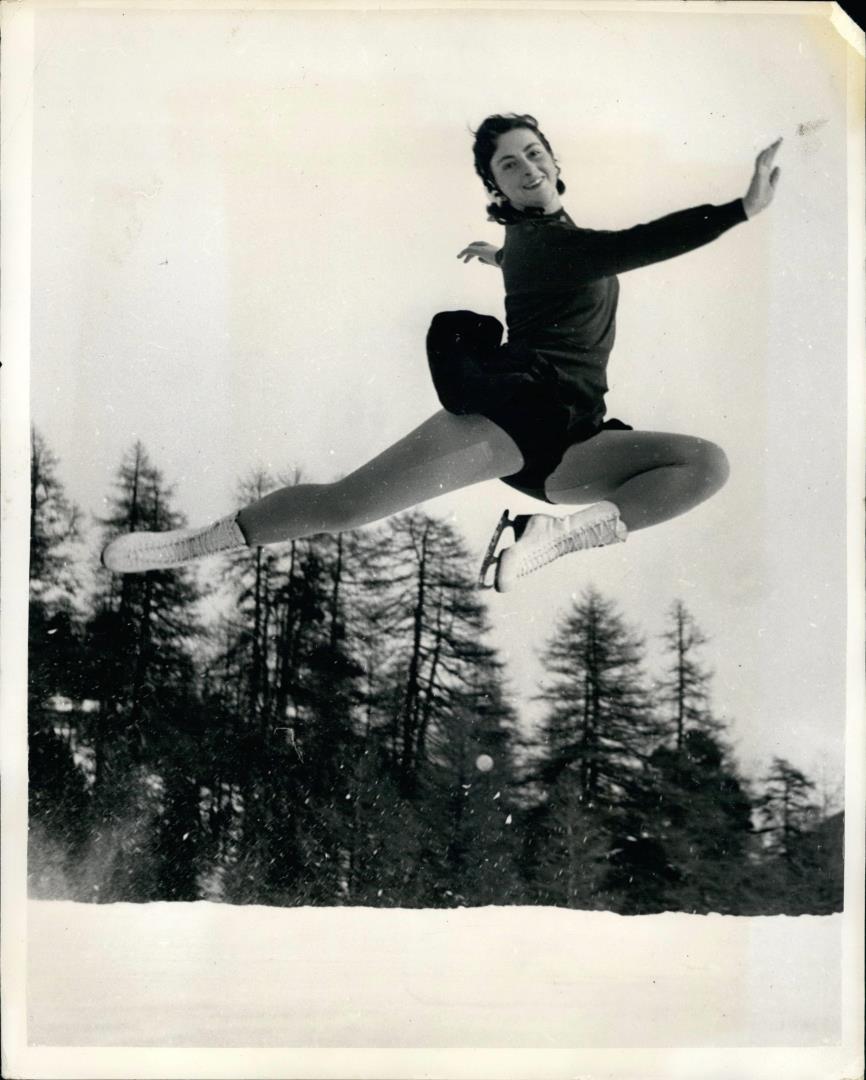

She was the Olympic champion who was offered a massive sum of money to tour the globe.

But even though Jeannette Altwegg was only 21 when she skated to glory in Oslo in 1952 and it seemed she had the world at her feet, this charismatic character packed in her career on the rink to help orphaned children in Europe.

The sport was shocked by her decision, not least because the India-born Altwegg – whose parents, Hermann and Gertrude (Muirhead), were Swiss and Scottish, respectively – had proved so single-minded and fiercely committed to excelling in her pursuit and had reached stratospheric heights.

However, after topping the Games podium, she argued that she couldn’t achieve any higher accolade and told the press: “It was the only thing I knew how to do and I couldn’t go on doing it for the rest of my life.”

At which point, she travelled to Dundee and performed her final exhibition in front of a packed arena at the Kingsway Ice Rink in April 1952.

Her story was all the more remarkable because Jeannette wasn’t just a glittering luminary in the land of sequins and double axels, but also displayed sufficient talent in tennis to appear at Wimbledon as a teenager.

Yet, later in life, the woman who died this year aged 90, regretted missing out on a normal upbringing because of the countless hours she spent training and fine-tuning her technique in sport.

‘I missed out on important things’

Jeannette, who enjoyed visiting Scotland and was proud of her mother’s roots, benefited from her work with leading coaches and made a name for herself on the British, European and world stage while she was still a teenager.

But as she told The Courier on a visit in 1952: “When I was 10, I had to give up school to concentrate more on skating and I had private schooling.

“I don’t think it occurred to me at the time it happened, but later on, I realised that I had missed the companionship of children the same age as me.”

Altwegg won a string of international honours and retained her European title in Vienna in 1952, after which she went straight to Oslo for the Winter Games.

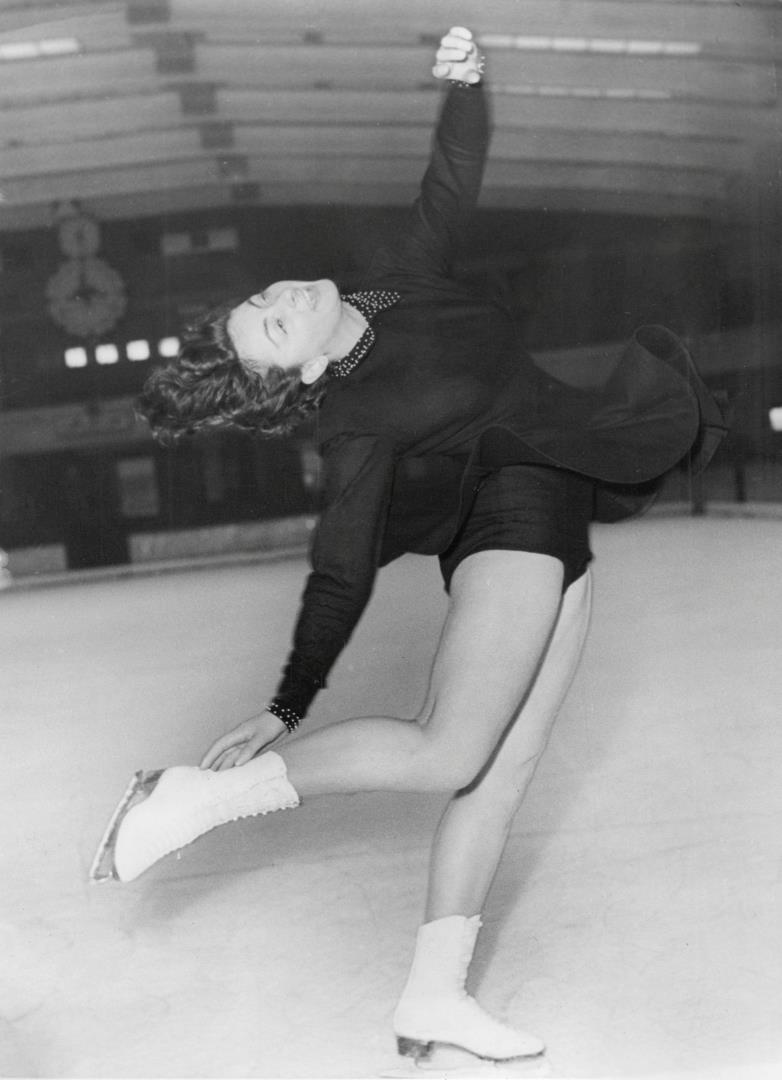

Working with her Swiss coach, Jacques Gerschwiler, she shrugged off a troubling knee injury and developed a new free skating programme that was set to Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffmann, and was as distinctive in its own right as Torvill and Dean’s subsequent success with Ravel’s Bolero.

After posting a strong score in the figures, she could only manage fourth place in her weaker event, although, in the end, she had just enough points to win gold ahead of the American Tenley Albright and Jacqueline du Bief of France.

It was the only medal of any description secured by her country at these Olympics, and served as a welcome morale booster in post-war austerity Britain, while her flair on the ice offered myriad commercial opportunities if, as most people imagined, she chose to turn professional.

But she was always her own person and said: “It was the top for me and the end of all my sports ambition when I was given my gold medal and saw the Union Jack being raised in front of 30,000 people in Oslo.”

These days, such an achievement would have earned Jeannette a fortune. And she would have been thrust into the media spotlight. She cared for neither.

Not that there weren’t offers. Just a few days after her Olympic heroics, she was sitting with her Scottish mother enjoying tea and cake when the Sydney Morning Herald reported on an astonishing development.

It said: “A cable (telegram) appeared from the Music Corporation of America, which confirmed a £2,000-a-week offer to tour the world.

“But Jeannette replied: ‘No thanks. Not for a million pounds. I’ve retired from competitive skating and I want to get married and have children.

“She added: ‘What’s the good of making a million? Tax would take most of it and I would get ideas far beyond me.

“Then I would have to keep up a position quite unnatural to me and waste a lot of money entertaining a lot of people I probably wouldn’t like.

“Besides, I’m just not interested in luxury. I’m interested in making friends and trying to help others.”

She soon proved true to her word on that score.

Jeannette Altwegg helped people who needed it

In September 1952, on the day of her 22nd birthday, Jeannette accepted a job as assistant to the headmistress at a kindergarten school in the British war orphanages at Pestalozzi Children’s Village in Trogan in Switzerland.

It could hardly have been a more dramatic contrast from the limelight in which she had dazzled for the previous decade.

On a salary of less than £3 a week, she worked very long hours – often from 6.30am to 7pm or 8pm – washing, ironing, sewing, scrubbing floors and carrying out whatever chores were required.

She loved giving support to children

It was a gruelling vocation, but Jeannette was in her element, looking after children from all over Europe, including Britain, France, Italy, Germany, Switzerland and Greece, who had lost parents in the Second World War.

She told the Glasgow Herald: “One of the greatest rewards for our work is to see the alert, normal and happy expressions in the faces of children who, when they first came here, looked only hopeless and frightened.

“It is more wonderful than anything you can imagine to feel the love and confidence these children gave you and the smiles on their faces.

“They had suffered so much pain in their little lives that it was a joy to see them coming to regard you almost as they would their own parents.

“They trusted you and we did whatever we could to make them feel special.”

Which, for Jeannette, meant far more than any lucrative contract.

Dundee turned out to welcome her

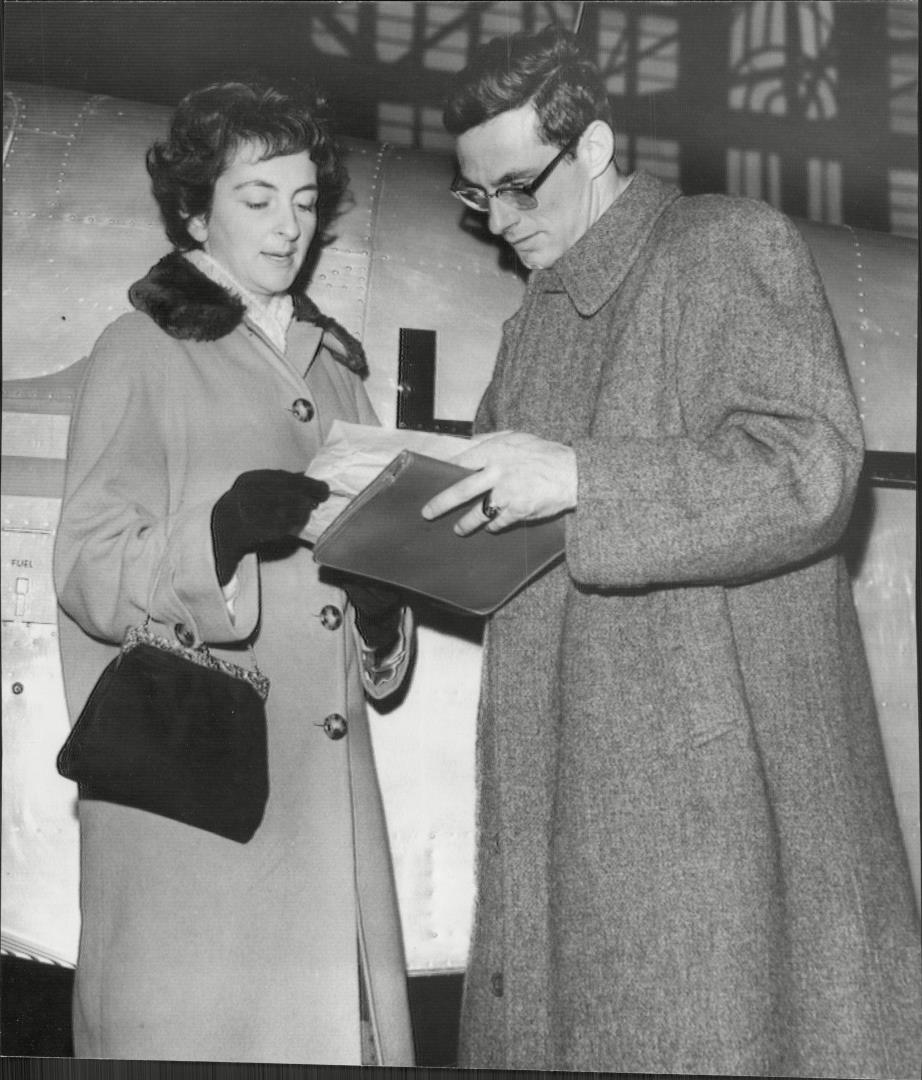

As the prelude to embarking on her new life, Jeannette made an emotional visit to Dundee and performed a dazzling routine at the Kingsway Rink.

The Courier was granted access to the performance and it was obvious that the newly-crowned Olympic champion made a positive impression on everybody she met during her time on Tayside.

It reported: “Miss Altwegg and local champions gave demonstrations between the periods of a challenge ice hockey match between the (Dundee) Tigers and Falkirk Lions.

“The Olympic star thrilled the audience with the effortless ease with which she performed a series of fascinating pirouettes and leaps.

“Local skaters taking part were the Dundee Dance Team, winners of the Nisbet Inter-City Cup; nine-year-old Susan Bruce, winner of the Templeman Junior Trophy; Mrs S Brodie and Mr R Black, winners of the dance shield; and Miss Pat Pearson, winner of the Dundee-Angus senior section.”

It was her swansong in the public gaze and while Jeannette was always delighted to meet and encourage children – she later married and had four of her own – she was never comfortable with being the centre of attention.

There were many decades where Jeannette refused to give any press interviews, preferring to look after her family.

One after another, the requests arrived on the 2oth, 30th and 40th anniversary of her Olympic exploits and one after another, they were all politely, but firmly, declined.

But eventually, in 2011, after being invited to the European Championships in Switzerland, she revealed that injury had played a significant part in her disappearance from the public gaze.

She said: “I messed up my knee in my last year of competing and at that time they were not able to operate on it as they are nowadays.

“But I don’t have any regrets. In a way, it’s good to stop when you are at your peak.

“It’s nice that you don’t go on and on and leave on your own terms.

Jeannette’s feats have not been replicated in the last 60 years.

Indeed, no British woman has even come close to winning an Olympic individual gold in figure skating since her victory, and the only other to have matched her achievement was Madge Syers, who triumphed in what was rather curiously termed the ladies singles at the London Olympics in 1908.

Ultimately, Jeannette wasn’t somebody seeking big bucks and a lavish lifestyle. She never made any secret of where her priorities lay.

As she said in 2011: “My family has been, and is, my career”.

In her eyes, they were her true legacy.

You might also like: