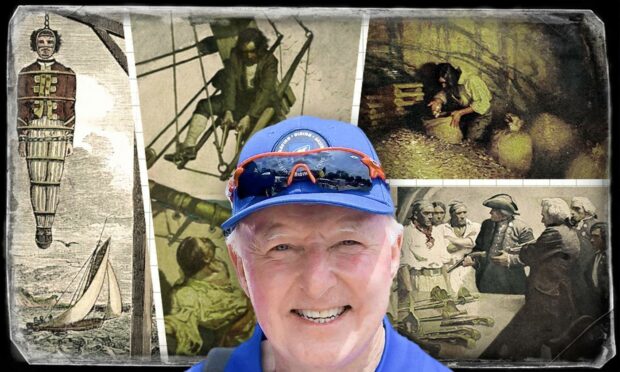

It’s a tale of privateering and piracy, murder and mutiny that screams ‘make me into a movie’ – and at least two film producers are hoping to do just that.

And it’s a tale born in Dundee, with connections to the Glasite church in King Street.

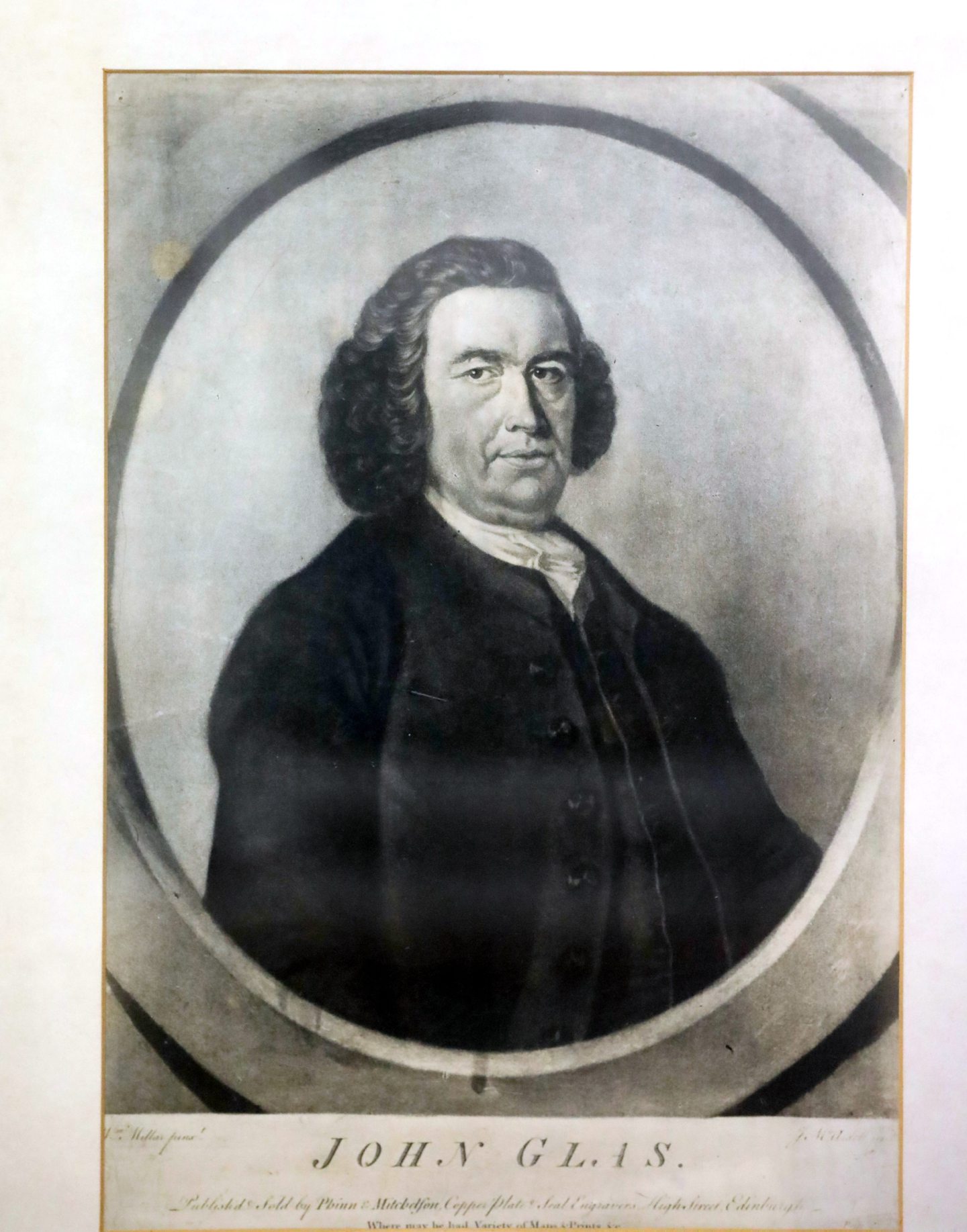

The church was started by John Glas in 1730 after he was stripped of his living from the Church of Scotland due to his ‘heretical’ beliefs.

While John was a gentle and respected man of God, one of his 15 children broke away and became involved in the dangerous world of privateering, in pursuit of the boundless riches of Africa and the New World.

His ambition would lead not only to his own bloody end by mutineers, but that of his wife and daughter too.

Captain George Glass, spelled with the extra s to differentiate him from his father, decided a modest life in Scotland wasn’t for him.

Growing up in genteel poverty, and witnessing the hurly-burly and excitement of Dundee as a thriving global port in the late 18th Century, George, born in 1725, decided that adventure and ultimately riches were his goal in life.

Acute intelligence

His acute intelligence marked him out, and he dedicated himself to education from an early age, training as a surgeon.

This opened the seafaring world to him, with ship’s surgeons greatly in demand.

For the first few years he learned sea craft in voyages to Africa and America, and merchants soon entrusted him with the command of their vessels.

His next step was to join the Royal Navy, which he expected to open up much wider opportunities and possibilities for him.

He travelled the globe – to Africa, the Caribbean and South America, working his way swiftly up the ranks.

But it was Africa’s Atlantic west coast that captivated him and changed his destiny.

Des Burke-Kennedy, author of George’s story in Murder, Mutiny and the Muglins, thinks his exploration of the rivers in the Western Sahara, Senegal and Guinea sowed the seed for the project that eventually prompted his bloody end.

George recognised the demand for riches from Africa to feed the industrial revolution, and embarked on a career of privateering, where private backers sponsored vessels to go forth and commandeer land, trading agreements and goods.

The problem was, Des writes, that privateering ‘was a far tougher and more dangerous existence than generally appreciated, often involving violence, bloodshed and death.

“George would have known this only too well, but it would have added to his excitement and encouraged him even more.”

There was a thin line also between privateering and piracy, and George crossed it on several occasions.

He also quelled seven mutinies, was imprisoned seven times and lost seven ships over the next few years, suffering financial hits but managing to build up his own personal wealth significantly.

There was a softer side to George; while back on visits to Dundee he met Isobell Hill and married her in 1750.

Their daughter, Catherine, likely named after George’s late mother, was born in 1754.

But his ambition was nowhere near satisfied by his exploits so far.

Des writes: “Behind all of his adventures so far, George Glass’s lifelong secret desire was to establish a deep water harbour or fort on Africa’s west coast or elsewhere in that general region… Such an establishment could guarantee him significant wealth and power.”

It seemed that in Guinea he did indeed find such a place, which he shrewdly named Port Hillsborough after the Earl of Hillsborough, president of the Board of Trade and Plantations in England at the time.

In London he negotiated a deal for a 20-year right of trading from the yet to be constructed port, and promised the equivalent of £3 million seed capital.

Unimaginable riches

Unimaginable riches beckoned, but one loose end had to be tied up: persuading the native Jalof tribe to come on side.

Confidently, George meticulously prepared a ship to sail to Africa – this time with his wife and child on board.

It was an unusual decision, given the dangers and hardships of life at sea.

Des interprets it like this: “If all went well, and why would it not, it was likely to be his last major adventure before retirement and perhaps even basing his family in this exotic place.

“A life of riches, servants, sunshine and peace. What more could either of them ask for?”

The outward journey passed uneventfully, almost in holiday mode as Isobell and Catherine endeared themselves to the crew, Isobell taking an interest in George’s work, Catherine starting work on an embroidered sampler and enjoying toys carved for her by the mariners.

On reaching the West African coast they headed towards Port Hillsborough – a site unidentified to this day and dropped anchor inshore at a safe mooring.

First horror

The idea was to look as unthreatening as possible to the Jalof, so a young crew member was dispatched to the shore alone, to try to attract attention.

Eventually, a lone Jalof warrior came out and approached. It looked amicable.

But in a split second, and in full view of the ship’s company, he drew out a scimitar and slaughtered the young lad before calmly retreating.

Glass decided he wasn’t going to give up, there was too much at stake.

They remained at anchor, and sent a bigger delegation to shore, laden with gifts.

This time things appeared to go better.

Negotiations began, agreements were signed. George had the documentation he needed, but he was suspicious.

By this time supplies were low, and the visitors procured supplies from shore.

Poisoned meat

Inspecting the meat sent aboard, George realised it was poisoned.

But rather than turn tail, George held fast, leaving the ship at anchor in a show of defiance and commitment to Port Hillsborough.

He set off with five men in one of the long boats to go and find food elsewhere – 1,100 miles away in the Canary Islands.

It seems incredible that he left Isobell and Catherine alone with the crew, but according to Des: “She must have been a very strong and confident woman to feel able to keep herself and her daughter safe without his help.”

And she needed to be strong, for while re-provisioning, George was arrested by the Spanish authorities and clapped in irons for 10 months.

Attack on the Glass ship

Meanwhile, back in Africa, his ship eventually came under attack by the Jalof, who slaughtered the chief officer and six other crew members.

Miraculously, Isobell and Catherine survived, hiding themselves below decks.

Half the crew was lost, it was likely that the next attack would be even worse, and remaining crew weren’t confident of their navigation skills – but they had to escape.

Under cover of darkness they slipped away and made it to Tenerife, where Isobell finally learned what had happened to her husband.

She began to fight for his release, and George finally walked free in October 1765.

Ordeal enough for the family? Far worse was to follow.

George’s ship was confiscated and they were all desperate to get home for Christmas.

Heading for home

He found passage for the journey home aboard the 120-ton brig, Earl of Sandwich, captained by William Cockeran, with a largely English crew and Irish bosun, one fearsome, heavy-drinking, unpredictable Peter MacKinlie.

Somehow, the crew got wind of the fact that a cargo of treasure had been secreted aboard into Cockeran’s cabin – in fact, an armoured chest with gold ingots, 270 bags of Spanish silver dollars, 3lb of gold dust, and an array of exotic jewellery and gemstones, and also George Glass’s personal gold wealth.

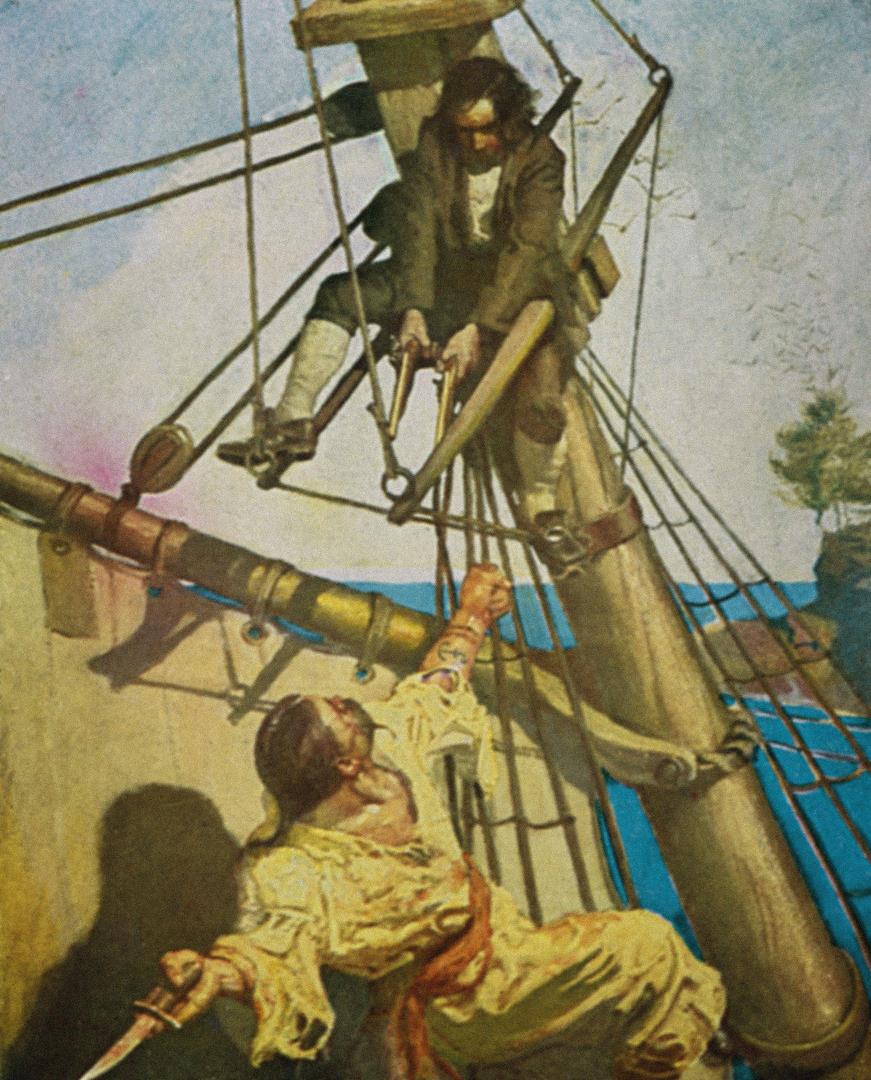

As the journey proceeded quite calmly, there were secret meetings to discuss murder and mutiny, followed by three failed attempts.

Within sight of Plymouth, on November 30, it was now or never for the inebriated crew.

They had stolen wine on board, and were in for serious punishment, anyway.

Slaughter begins

MacKinlie first attacked Captain Cockeran who was eventually slaughtered by an iron bar wielded by the ship’s cook, Gidley.

Next Gidley slaughtered the two young cabin boys, while MacKinlie ambushed George Glass as he left his cabin, knifing him open, with another crew member running him through with a sword.

Isobell and Catherine, whose 11th birthday had been celebrated the night before, climbed to the upper deck and confronted the mutineers.

Rather than kill them on board, which superstition said would bring bad luck to the ship, they were flung overboard into the freezing depths, clinging together as they screamed for mercy.

The mutineers then turned tail for Ireland where they planned to take what they could of the treasure and bury the rest for later retrieval.

They made such a spectacle of themselves on their way home with their appalling behaviour and open-handed spending of gold and silver that they soon activated the bush telegraph, and were all arrested.

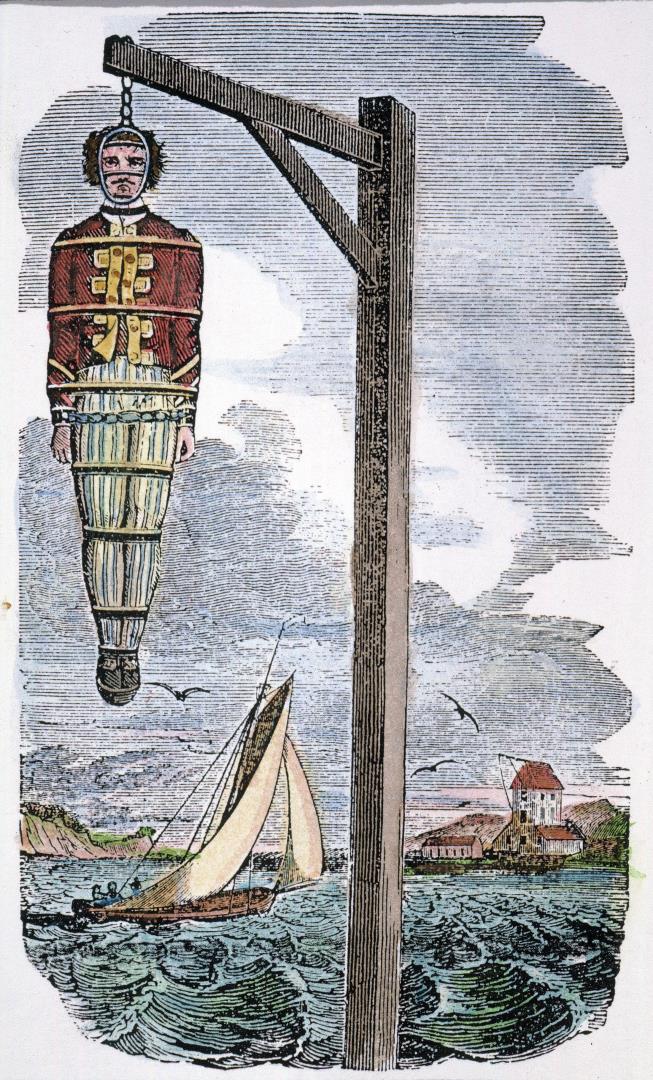

The upshot of the grim tale is that the four murderous mutineers were hung in Dublin, their bodies exhibited at the mouth of the River Liffey until they began to slip out of their irons.

Two were buried on the shore, but MacKinlie and Gidley’s bodies were transported to Dalkey and taken to a jagged outcrop knowns as The Muglins.

There a special gibbet was raised, from which the two bodies were suspended and left to swing in the wind as a warning to passing ships’ crews.

In his book, Des Burke-Kennedy shares every conceivable detail of this bloody and tragic episode, gleaned from detailed and eye-witness accounts.

But, he wonders, was Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island inspired by the dreadful tale of George Glass?

RLS was born within a short walk of the Glasite church in Edinburgh and he holidayed in Dundee when he was nine.

Robert Louis Stevenson connection?

Des, who lives in Dalkey overlooking the bay and the Muglins, pieces together a scenario in which RLS knew about both John Glas and George Glass, and drew on what he’d heard for Treasure Island.

“It is a simple but captivating tale, the thought of a place where fortune awaits, a few good people on a voyage, a new ship and hastily hired crew, an overheard conversation of treachery, a group of hired hands who turn out to be desperate pirates and murderers, a ringleader who directed all the mayhem, the planning of a mutiny, sword fights and death… each and everyone of the elements of Treasure Island feature in our Muglins saga, with the exception of the happy ending.”

Des has been to the Muglins to lay a wreath.

He said: “As the murderers have received a great deal of publicity over the years, I was always saddened by the fact that George and his family were almost forgotten.

“His achievements for that time were quite extraordinary by any standards.

“To try to balance the karma, that is why I recently went out to The Muglins island off the coast of Dalkey to lay a wreath in the memory of each of the family members.”

There are also plans to lay wreaths in Dublin and on John Glas’s grave in Dundee Howff cemetery on November 30.