It began as a pleasant hillwalking excursion in the Highlands for a group of four girls, two boys and two teachers from Edinburgh.

But, 50 years ago, it ended in the deaths of six of the party, buried in freezing snow in the Cairngorms, less than half a mile from a mountain hut.

There had been no indication of the tragedy that would engulf them as they travelled up from the central belt on a trip they had planned for months.

Yet once they were on the Cairngorm Plateau, and as the weather deteriorated, almost everything that could go wrong did go wrong for them and those trying to rescue them in appalling conditions in November 1971.

The shocking events cast a ghastly pall even among experienced climbers and mountaineers who could hardly believe what had happened to the youngsters.

Flt-Fgt George Bruce, leader of the RAF Kinloss mountain rescue team, summed it up when he said: “This is the worst accident I can ever remember.”

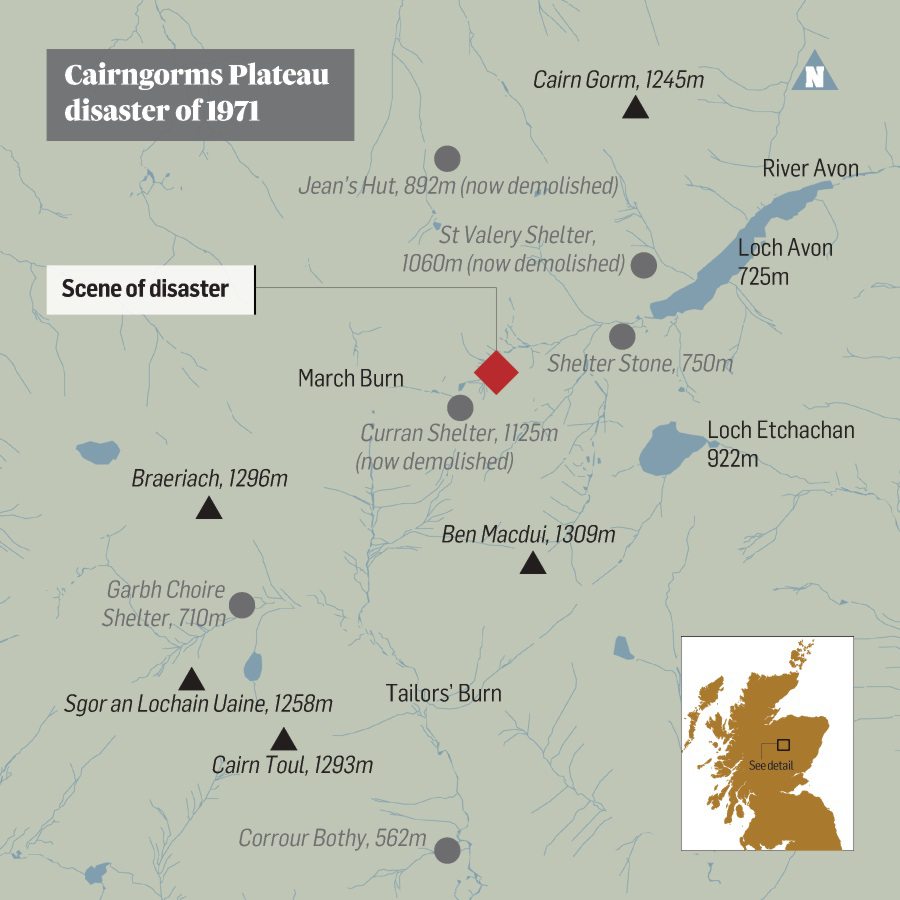

The expedition had started auspiciously enough, when six teenage school students and their two leaders set off from the Lagganlia Outdoor Centre on November 20 for a challenging and arduous two-day winter exercise to cross the exposed Cairngorm Plateau from Cairn Gorm mountain to Ben Macdui.

But the Ainslie Park School youngsters, Raymond Leslie, Susan Byrne, Lorraine Dick, William Kerr and Diane Dudgeon, all aged 15, and Carol Bertram, 16, and those in charge of their safety – Catherine Davidson, a 21-year-old student at Dunfermline College of Physical Education in Fife and 18-year-old trainee instructor Sheila Sutherland – were almost completely unprepared for the ordeal that beset them for most of the next 48 hours.

The Curran shelter was plan B

The excited youngsters had access to specialised mountaineering equipment, including Icelandic sleeping bags, ice axes, crampons and cagoules, but they lacked any experience of responding to the atrocious conditions which can rapidly materialise and escalate in the Cairngorms, especially in winter.

Prior to setting out, the weather forecast was at best questionable, at worst sufficiently negative to dissuade them from embarking on the venture at all.

But Miss Davidson had decided that if matters deteriorated, she and the children would head for the high-level Curran shelter, a small stone bothy that they believed would offer them sanctuary in an emergency.

Not long after they had embarked on their journey, the group was struck by a severe blizzard.

But there was no immediate panic at that point as they implemented plan B and attempted to reach the shelter.

However, when the white-out prevented them from locating the hut, Miss Davidson decided to create a forced bivouac – a temporary camp without tents – on an exposed plateau, where the party ended up stranded for two nights in what were later described as “incomprehensible” conditions.

There was no respite from the maelstrom in an area where snow accumulations happened quickly and enveloped everything in their wake.

The emergency teams were hampered

By now it was clear that the party was in serious trouble and a full-scale rescue operation was mounted by Inverness police at first light, in an urgent search for the missing eight people.

The Press & Journal reported how matters unfolded from that point as it became obvious that this was an unprecedented situation in the mountains.

It said: “High winds prevented a helicopter from taking off from RNAS Lossiemouth and an RAF helicopter left from Leuchars in Fife.

These poor folk never had a hope. How on earth could this happen?”

Quote from a newspaper article on the tragedy

“But it was unable to reach Corrour Bothy at its first attempt and flew to Aviemore for a briefing with rescuers who were increasingly concerned.

“The helicopter later found the girl, Miss Davidson, between Corrour Bothy and Rothiemurchus.

“She was in the advanced stages of hypothermia and her hands were frozen solid. She was flown to Aviemore and transferred by ambulance to Raigmore in Inverness.”

Another survivor, Raymond Leslie, was also taken to the same hospital and, despite being in a critical condition, at least was in safe hands.

But the others were less fortunate.

The Kinloss team, led by Flt-Sgt Bruce, had dogs with them and went to the assistance of some of the staff from Glenmore Lodge, who had been out all night checking bothies and were on their way back through treacherous, unrelenting waist-deep snow in Strathnethy.

Yet, by this stage, even as they ploughed on, the awful realisation dawned on them that this was a salvage rather than a rescue operation.

During their second night in the bivouac location, the children had started to become delirious, stricken by the effects of hypothermia.

And the mountain rescue teams who battled through the snow were met with an appalling scene: six dead bodies, partially or wholly buried in the snow, with one of the victims engulfed by a drift that was four feet deep.

One man later told the Press and Journal: “These poor folk never had a hope. How on earth could this happen?”

The trip should have been called off

In the aftermath, it emerged that the four teenage girls who had perished were “inseparable friends who always went together on adventure courses”.

And they had jointly celebrated Carol Bertram’s 16th birthday with a cake and candles on the Saturday November 20, the day before all their lives ended.

None of their parents had been given any indication that the school trip might involve anything remotely hazardous at what was the beginning of winter.

But, just a week later, they found themselves in the midst of a packed Insh Church in Strathspey, during a poignant memorial service for the lost.

‘We must cherish the human spirit’

Grief-stricken parents, relatives, friends and school officials huddled together in the church to pay their respects and those who could not gain entry were allowed to listen to the short service through loudspeakers in the graveyard.

Even from within the building, the now-tranquil peaks of the mountains which had proved so destructive were visible to the assembly.

The Very Reverend Dr R Leonard Small, told the gathering: “These young people deliberately chose in the middle of winter to go climbing.

“They knew that it was going to be cold and would require effort and they still chose to do it. I thank God for that spirit.

“Let adequate safeguards be established, but let nothing quench this spark.”

New regulations came into force

A fatal accident inquiry was held in Banff in February 1972, with Adam Watson acting as the chief expert witness for the Crown.

It soon emerged that the consent form issued to parents did not state that winter mountaineering was involved and only one of the parents had been told the outing was going to be to the Cairngorms.

The inquiry reported that the deaths had been due to cold and exposure and made a series of recommendations, including that school parties should be led by fully qualified instructors and accompanied by certified teachers; parents should be given fuller information about outdoor activities; and suitable locations for summer and winter expeditions should be identified in consultation with mountaineering organisations.

The advocate for the parents suggested that the overall leader of the expedition and the principal of Lagganlia should be blamed for the disaster, but the inquiry did not rule that anybody was at fault.

John Allen, who was the leader of the Cairngorm Mountain Rescue Team from 1989 to 2007 (and joined the organisation in 1972) knows how the mountains can be a playground, a sanctuary or a place of genuine danger.

He was horrified by the deaths of the youngsters 50 years ago, but, as he told me, it’s important to avoid acting with the benefit of hindsight.

He said: “Sometimes, the bravest decision in these circumstances is to turn back, to leave the adventure for another day, and write off the time and expense of reaching the tipping point.

“On this day, the group continued, eventually becoming disorientated and misplaced and exhaustion and hypothermia naturally followed.

“The scale of the losses sent a shockwave through the wider public who had, for the most part, not understood that a disaster of this magnitude could occur on home shores, especially within the education system.”

He added: “The inquiry into the Cairngorm Plateau disaster had a profound effect on outdoor activities in the UK, but, despite all that, very few voices were raised in favour of ending such activities and I understand that.

“No rescuer ever rushes to judgement, let alone blame, when these things occur.

“Everyone involved knows that under different circumstances, in different times, it could have been them.

“There is always a back story, a combination of circumstances, of history, and decisions made by others.

“But, whatever improvements have taken place in the last half a century, whether in the equipment and vehicles we now have or the detailed forecasts available to those going on to the mountains, you can never entirely rule out the possibility of things going wrong.”

An epitaph for the fallen children

Mr Allen’s acclaimed book, Cairngorm John, details the remarkable work done by the CMRT and other groups to safeguard lives in the high places.

But its final words could serve as a fitting epitaph to those who died in the Cairngorm Plateau on that terrible weekend.

He said: “Beyond our skills and strength, expertise and experience, we must accept the world as it is, including change however tragic.

“All we can do is mind how we go on the earth and look after each other and, if we cannot turn sadness into joy or death back into life, friendship and remembering will have to do.”

- Cairngorm John is published by Sandstone.