In the dying days of 1904, the unearthly howls of a wolf in the grip of blood lust pierced a Borders night.

It was the last stand of a killer that had slaughtered scores of sheep in the previous fortnight.

That final night, December 28, the wolf had been drawn to a farm by the smell of blood from a recently-deceased horse.

Next morning, however, the wolf was dead: cut in two by the London to Scotland express.

During its run of freedom, supposedly from a private collection, the wolf had outwitted hunters drawn from Fife and Lothian.

They turned up in Northumberland with two she-wolves from a menagerie hoping they would induce the depredator to show itself. It didn’t.

It was late summer when the wolf broke free from a mansion near Newcastle but it behaved until the weather got cold.

As December began, it edged closer to settlements and the killings began. In just one week, 21 sheep near villages were killed. On the moors, many more were found with their throats ripped out.

More than 200 men bearing 40 guns gathered to kill the wolf. They did spot it but the animal was very fleet of foot and dodged between the gunmen to freedom.

By December 15 the casualty rate was well into the hundreds and farmers formed the Hexham Wolf Committee to offer a reward for its elimination.

On both sides of the Border, those in isolated farms were living in terror. One farmer returned to his moorland property late one night to find the wolf loitering outside. He bolted inside, seized his cat and threw it to the wolf.

Just before Christmas an array of horse riders and fox hounds set out in pursuit. To their surprise, they saw a fox and the wolf running as companions. Both outflanked the hunters.

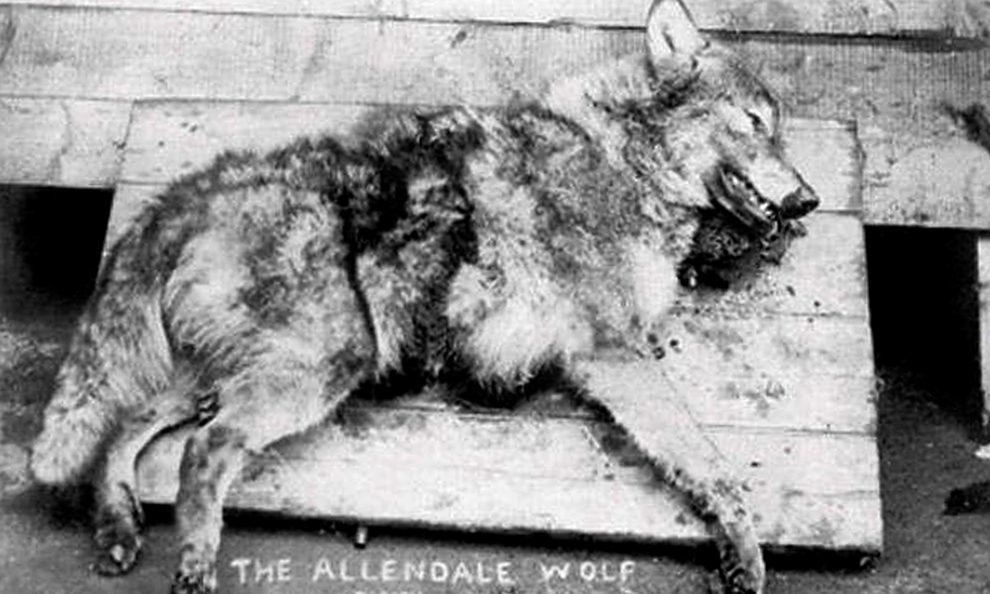

On the morning of December 29, however, railwaymen found a wolf on the track. The Courier reported: “The animal had a shaggy coat, long ferocious jaws, pricked ears and glaring eyes.”

Curiously, when the owner came to identify it, he insisted the wolf was far too old to be his.