Maureen Kerr never expected to spend 15 years on St Kilda, but that’s the captivating allure of this remote archipelago in the Western Isles which casts its spell and drags you into its mystique.

She worked as a chef on the military base, one month on and one month off, flying in and out by helicopter, and while there were many challenges, there was also a rich well of inspiration for her to tap into as an author and artist.

As she said: “I have walked it, written about it, painted it, drawn it, and photographed it in all its moods; in howling 120mph gales, in deep, pristine snow, high up on the cliff faces and boulder fields and down in the old settlement in Gleann Mor.

“It is an artist’s paradise with its changing, shifting clear light and dramatic cloud and weather patterns. This was a field trip of a lifetime for me.”

Yet, in the midst of juggling her various assignments between cuisine and culture, Maureen began reading the diary which was kept by one of the school teachers, George Murray, between 1886 and 1887.

It describes just how hard and often grim life was for the men, women and children who dwelt on the edge of the world until their descendants were finally evacuated in 1930 – a place in its own little bubble, where Christmas was celebrated on January 6 and New Year’s Day arrived a week later.

And while she was there, she noticed the past and present worlds colliding.

She told me: “In 1997, I went out to the Blasket Island archipelago off the South West coast of Kerry in Southern Ireland, another island group which has similarities with St Kilda.

“The inhabitants had to be evacuated for much the same reasons as happened on St Kilda because life simply became unsustainable. I had read extensively about St Kilda, but I never imagined that I would get there.

“However, I came back from the Blaskets and, the following year, met an old friend of mine I hadn’t seen in years in the main street in Dunoon.

The news was like a bolt from the blue

“After our initial blethers, I remarked that she looked a bit harassed. She said that was exactly the case because she was trying to get some last-minute shopping done before going out to St Kilda the following day. What….!

“I remember grabbing her jacket front and saying fiercely: ‘Get me there’.

“And the next year, there I was, working as a cook for the NTS parties who went out to St Kilda in the summer. I already had lots of experience, having worked my way all over the Highlands in fishing and shooting lodges, cooking for all and sundry and could find my way around a kitchen alright.

“Being a chef was never my metier in life, but it sure got me to the remote and beautiful places I craved. And two years later, one of the chefs in the base left and I applied for the job and got it. And I spent 15 years out there.”

Maureen delved extensively into the life of Murray, whose recollections and reminiscences of his time on St Kilda are both painfully honest, poignant and beautifully observed, highlighting the harsh environment in which the Victorian members of the community lived – and died.

The latter happened on a regular basis, which was hardly surprising, given how difficult it was for doctors and nurses to make the arduous journey from the mainland to beyond the Western Isles.

Maureen said of the diarist: “His intelligence, energy, fairness, generosity of spirit and humour are all set in a well-determined path for the future, but there is no doubt St Kilda came as a bit of a shock to him and we see him bewildered and angry, incredulous and, in some cases, fearful for his safety.”

She added: “One of the diary entries of George’s from February 28 [in 1887] left a lasting impression on me.

“It was of Annie Ferguson, who at 10 years old and one of George’s promising pupils, had fallen ill with tetanus [lockjaw].

“The poor girl lingered, suffering unimaginable pain for almost two weeks, until she died on March 10. Her body was so contorted with pain that it was almost unrecognisable. George’s description of this event makes harrowing reading and it must have been difficult for him to write.”

Obviously, life has moved on since these days more than 130 years ago, but Maureen has no illusions about the demands which are placed on people when they are billeted in such a far-off location as St Kilda.

It’s not for everybody and she revealed some of the issues which had confronted her before she left the military base in 2015.

She said: “To live out there, you obviously had to be accepting of island life, but life on THIS particular island was one where if there was an acute emergency involving one of your family, it was not always possible to get off to attend to it.

“I remember someone whose daughter contracted meningitis and was in intensive care and, due to the adverse weather conditions, he couldn’t get off St Kilda and he was quite distraught.

“You also had to be self-sufficient mentally, enjoy your own company and in my case as a chef, to be super adaptable if supplies were running low.

“The highlight of the day was always mealtimes for everyone and the food had to be top notch at all times. They soon let you know if it wasn’t!

“I could be cooking for between 14 and 45 personnel. There was our staff, plus contractors out to execute repairs and maintenance and military personnel and there was only me – one chef to see to it all.

It was a long hard shift for the chef

“My day started at 5.30 or 6.0am depending on numbers on the base. The daily prep was done and then it was breakfast at 8am. Then, from 9am, it was straight into getting lunch ready.

“This finished at 1.30pm and, theoretically, I would have time off. If numbers on the base were low, yes I could get out for a bit before coming back to the cookhouse to start dinner, but latterly, it rarely happened.

“Woe betide if you were late in opening the door for dinner after having got everything out on the servery. There would be much banging and shouting to open up. And that was a scenario to be avoided at all costs.

“My day usually finished around 7.45-8pm, but if military trials were ongoing, it might be nearer 9.30- 10pm. Then I would get in a hot bath and collapse into bed and do it all again for the rest of my month on duty.

“You also had to be tolerant of extreme weather. As a writer and artist, I got out whenever I had time away from the cookhouse, which wasn’t much fun in the low light in winter biting cold. Sometimes I had to make myself go out.”

But, as she observes, it was well worth it to savour St Kilda’s unique ambience.

Maureen now works at the Scottish Crannog Centre in Kenmore in Perthshire, but she has never forgotten the myriad sights, smells and sounds – or indeed silence – which were part of her day-to-day existence on St Kilda.

Not that it was always quiet. Yes, the islanders were a close-knit religious community, but as Murray’s diary spells out, they were subject to the same human weaknesses, jealousies, rivalries and desire for companionship and adventure as anywhere else – even if they had no truck with the notion that the festive season should be celebrated in December.

She told me: “George says clearly in the diary that Christmas was celebrated on January 6. It was fairly common in the Western Isles to stick to the ‘old’ calendar. Christmas was hardly noticed at all, but as for New Year – well, that was a different kettle of fish altogether.

Happy New Year in mid January

“It was celebrated out on St Kilda on January 14. There would be [a lot of] feasting and drinking on that day. And many island communities still acknowledged the old calendar right up until the 1940s and 50s.”

By that stage, of course, the islanders had left they roots forever and been relocated to the mainland, with several of them given jobs in forestry even though they had never seen a tree in their lives.

And George Murray, a popular church figure who served as a chaplain to some troops stationed in Inverness, had gone as well after suffering a fatal brain haemorrhage at the age of 57 in 1918.

Even though it was many years since he had left St Kilda, the memories were ingrained in his heart – as it is with Maureen herself.

She said: My abiding memory of my time out on St Kilda, apart from the stunning scenery, would be releasing the wee stormy petrels out into the night. I would take them to the cliff top, get them out and let them go.

“The smell from these wee birds is very distinctive. It can be nothing else. It is a sort of metallic, musty ancient smell and you never forget it.”

George Murray: A Schoolteacher for St Kilda’s Diary by Maureen Kerr is available from the Islands Book Trust.

More like this:

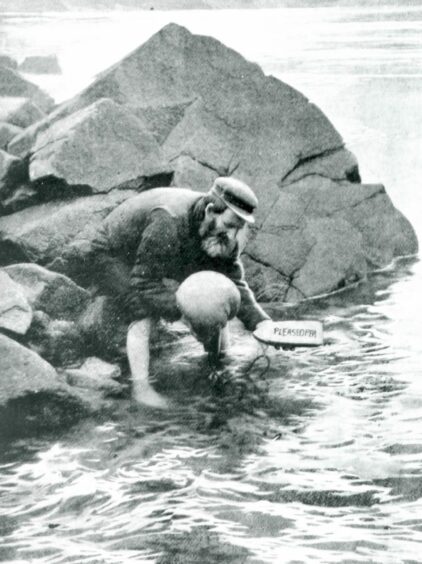

Silence surrounds mystical St Kilda 90 years after mass evacuation of residents

Legacy of National Trust for Scotland worker Davie Fraser lives on at beloved St Kilda