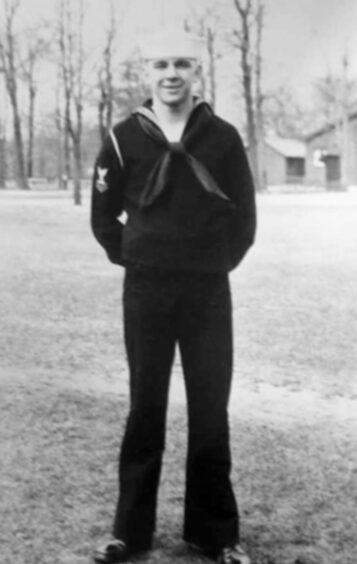

Robert Adair Anderson was just 21 when he was killed at Pearl Harbor.

He died on the ageing battleship that, for many, has come to symbolise the entire event.

The forward deck of the Arizona was struck by a 1,760-pound bomb that triggered a massive explosion and the ship burned for two and a half days.

Robert’s father, James Clark Anderson, was a carpenter to trade from Dundee and the son of a yarn bleacher whose parents married in Brechin in 1862.

He was among the nine million who emigrated to America between 1830 and 1930.

He went to start a new life in Kansas City, Missouri, with his English wife, Josephine.

By 1941, the military situation across Europe was becoming increasingly desperate for the Allies and the dark clouds of war were casting their shadow further afield.

Robert was the fourth of the couple’s five children and joined the American Navy aged 19 in 1939 and was assigned to the Arizona as a Gunners Mate third class.

One report stated that in a letter to his family, Robert wrote that he hoped to be home for Christmas, “to see all the family once more before anything happens that will keep me away for a long time”.

It was not to be.

I am a very proud navy mother to have had a son give his life for his country.”

Robert Anderson’s mother, Josephine

On December 7 1941 there was a surprise attack by the Japanese on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii which would trigger America’s entry into the Second World War.

Just before 8am local, time, an assault involving more than 350 Japanese aircraft led by Mitsuo Fuchida, launched from a fleet of aircraft carriers.

They were supported by a number of submarines, each carrying a miniature submarine with a crew of just two men whose task was to stop American battleships leaving Pearl Harbor and reaching the open sea where they would have room to manoeuvre.

Fuchida fired a flare from the cockpit of his plane, the signal which began the attack that would claim the lives of more than 2,300 American service personnel.

With no American planes in the air, Fuchida’s squadrons flew unchallenged and the carnage began as the meticulously planned attack targeted ships and grounded planes.

The American Air Force thought the greater threat to their planes on the ground was sabotage from Japanese nationals and had grouped their planes together so they could be easily guarded, but it made them vulnerable to aerial attack.

The Japanese took full advantage.

Figures vary, but according to the Imperial War Museum, 18 US warships were sunk or damaged and 188 aircraft destroyed in an attack that lasted less than two hours.

Anderson’s ship, the Arizona, was hit within minutes.

Although heavily armoured and classed as a ‘super-dreadnought’, the 185-metre ship was old, having been launched in 1915.

Suffering three near-misses and four direct-hits from 800-kg bombs, the last bomb penetrated her deck and detonated within a powder magazine.

The massive explosion made the ship ‘jump’ around 15 feet in the water before it broke in two and collapsed her forecastle decks, creating such a huge cavity that her forward turrets and conning tower fell 30-feet into her hull, killing 1,177 of her crew.

Despite the catastrophic damage to the Arizona, the ship’s damage control officer, Lieutenant Commander Fuqua remained at his post directing rescue efforts.

He was later awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions during the attack.

The Japanese forces turned for home, but crucially, much of the harbour’s infrastructure and fuelling systems remained intact.

Congress statement

The next day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed a joint session of Congress, describing the catastrophe as “a date which will live in infamy”.

America was at war.

Just six months after Pearl Harbor, America caused irreparable damage to the Japanese Navy at the battle of Midway in June 1942.

However, the war between the Allies and Japan would grind on until 1945.

Today, the Pearl Harbor area is a designated national historic landmark and in 2016, Japanese premier Shinzo Abe visited the site and offered “sincere and everlasting condolences” to the victims of the attack.

Robert, along with some 900 of his shipmates, remains entombed within the hull of the Arizona and a memorial in his honour has been placed in the Mount Moriah Cemetery in his hometown of Kansas City.

While the war continued, Robert’s mother honoured her son’s legacy.

In October 1942, the Kansas City Times reported that a tree would be planted in memory of Robert, while the Kansas City Star informed its readers that Mrs Anderson had received the Purple Heart medal which had been posthumously awarded to her son.

Perhaps most poignantly, the American War Mothers, an organisation formed during the First World War, rallied to the support of the next generation of mothers whose children had gone to war.

After a meeting of the American War Mothers, Mrs Anderson said: “I am a very proud navy mother to have had a son give his life for his country.”

In 1944 a number of newspapers carried an image of Mrs Anderson receiving an autographed copy of the song “Remember Pearl Harbor” from band leader and composer Sammy Kaye.

Robert’s name lived on through his niece Roberta Bloch, who was named in his honour.

The attack continues to fascinate historians and military tacticians and has been the subject of numerous books, films and documentaries.

More like this:

Doctor behind the wire: Tayside woman publishes father’s wartime diaries

The mystery of the Montrose pilot who vanished during the Battle of Britain