It was just another cold December day when three Aberdeen lads went out together and threw stones into a burn in 1958.

But suddenly, even as the trio of nine-year-olds, Colin Moir, George Bissett and Peter Wadsworth, were enjoying their outdoor entertainment, they found themselves in the midst of another, more thrilling adventure.

One moment, the blithe lads were staring at the water; the next, they were all gazing directly at a man who had appeared in front of them and told them: “Dinna be feart. I’m Ramensky. And I’ve escaped from Peterhead Prison.”

The words would perhaps have sent shivers of apprehension down anybody’s spine, but not in this case.

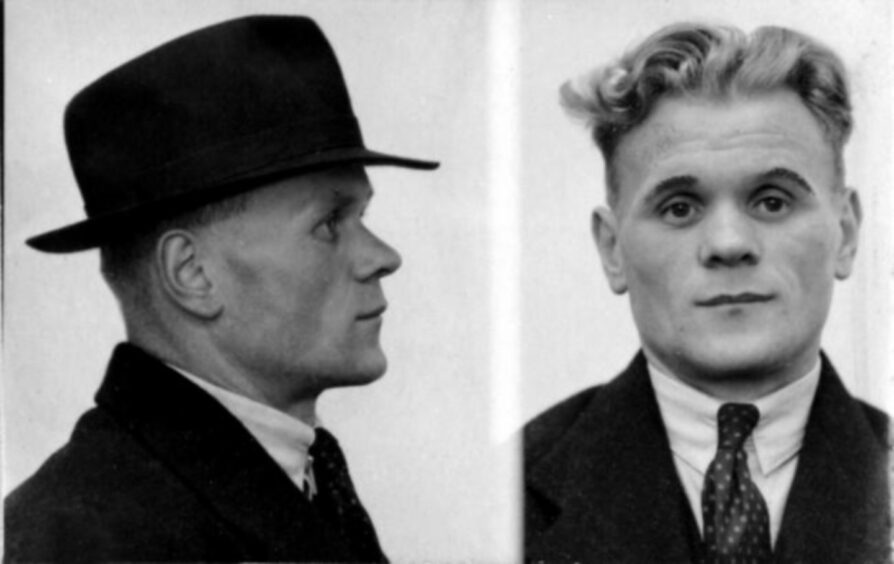

The boys knew exactly who he was and had heard all about the exploits of ‘Gentleman’ Johnny Ramensky, escapologist, safe-cracker and Second World War hero who was awarded the Military Medal.

But now they were presented with a dilemma.

What should they do when he asked them to bide their time and allow him to see his wife again?

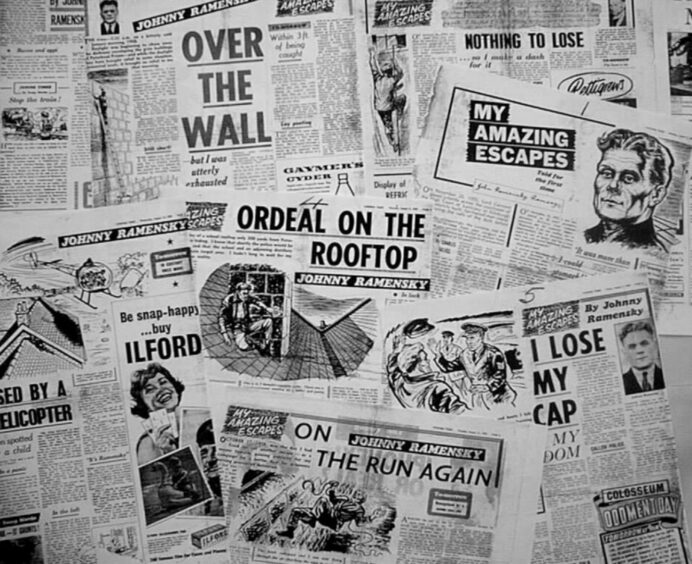

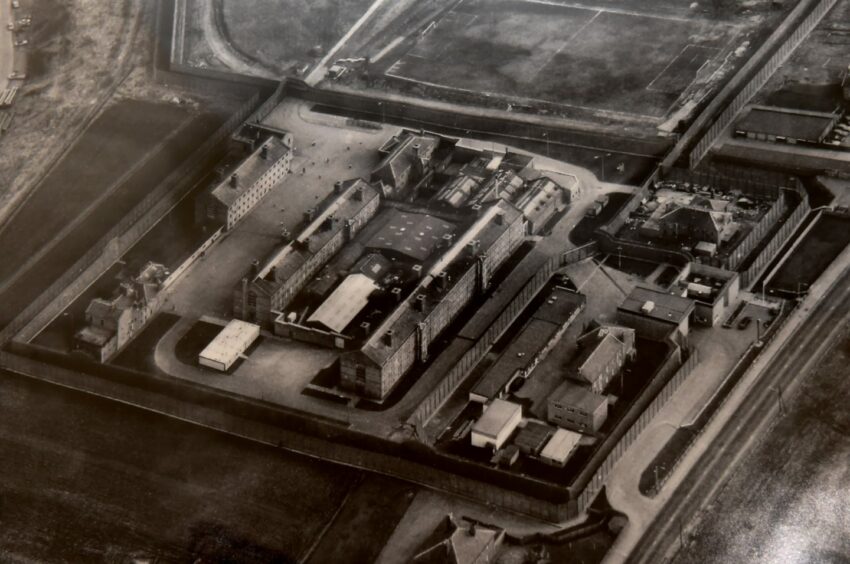

Ramensky had already proved his expertise at escaping from captivity.

This was the fifth time since 1952 that he had outwitted his guards and vanished off the premises and questions were later asked in the House of Commons about whether he shouldn’t simply be “given a key”.

By the time he bumped into the three youngsters, though, he had been on the run for nine days and, at 53 years of age, was clearly feeling the effects of continually trying to evade the police dragnet and living off his wits.

As Colin said: “We knew it was Ramensky before he even spoke. He had on a green polo-neck jersey, dungarees and a long navy blue jacket.

“Their minds were made up for them when a police car appeared.”

Excerpt from Press & Journal report

“He told us he was wanting to see his wife (Lily Mulholland), whom he hadn’t seen for years, and that his feet were very sore.”

He carried on chatting to the lads and asked them their names and ages, although they later reported he had spoken gently and without any threat.

On the contrary, he said with a pleading voice: “I’ve got a wee grandson, but I have never seen him.

“Now, don’t tell anyone that you have seen me. You can tell your mother, but don’t tell her until the night.

“Don’t tell the police. If you don’t tell them, you will be doing me a favour and, perhaps, I will be able to do a favour for you some day.”

As he bade his leave and started walking away slowly towards Parkhill, Ramensky called back: “Cheerio, lads”.

And that was the last they saw of him.

Once he had disappeared from view, Colin, George and Peter began discussing what they should do in such extraordinary circumstances.

Colin was insistent that he wanted to go and break the news to his mother but his friends voted for telling the police about their strange encounter.

However, as the Press & Journal reported: “Their minds were made up for them when a police car appeared. They stopped the car and let the officers know what had just happened.

Johnny was stoical about his fate

“The police took them into the car and the lads directed it to the spot where they had recently seen Ramensky.

“And, less than half an hour later, he was caught at Lovers’ Walk, near the River Don at Persley in Aberdeen, and gave up without a struggle.”

The P&J asked Colin if he had been frightened when he and his pals were approached by Ramensky.

But his response summed up the mixed feelings that so many people throughout Scotland had about this enigmatic figure.

He said: “We were a wee bit afraid. But we were more scared in the police car than when Ramensky was speaking to us.”

His capture caused a hubbub

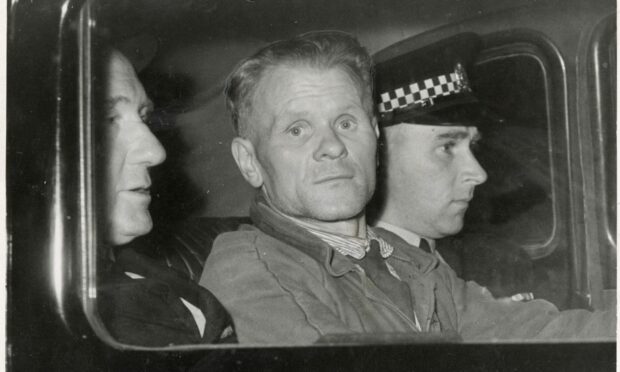

There were astonishing scenes the following day when the prisoner was accorded a “film star” reception as he left the divisional headquarters of the North-Eastern Counties Police in Lodge Walk in Aberdeen, to be returned to Peterhead Prison, where he had already spent so many years of his life.

And it was as if many in the Granite City were determined to have their fling with celebrity, even if it was just catching a glimpse of “Gentleman Johnny”.

The P&J highlighted how crowds congregated during the day as the news spread that Ramensky would shortly be leaving the police HQ.

It stated: “All afternoon, little knots of people had been gathering in front of the premises in the hope of catching a glimpse of him.

“Excitement mounted every time the front door was opened.

“Just after 4pm, a small police van drove up and reversed along the side of the building.

“By this point, the crowd numbered about 200, most of them women, and they surged past the van to take up vantage points.

There is a lot of interest because he was such a complex individual, and his legend lives on.”

Alex Geddes of Peterhead Prison Museum

“The driver attempted to reverse close up against the side door, but was unable to manoeuvre properly because of the crush.

“A sergeant took over and succeeded in getting the van in position. But a number of young children were being crushed, close to the vehicle, and because of the danger, the van was driven to the front of the building and reversed against the front door.

“Seconds later, with police screening him from the public as much as possible, Ramensky was hustled into the back of the van.

“It was practically dark and few of his ‘fans’ saw him. But they made up for it by cheering wildly and waving and gesticulating as the van drove off.”

This was Beatlemania a few years before the Fab Four even hit the charts!

There’s no real mystery as to why Ramensky – who always avoided violence and preferred puzzles to punch-ups – commanded such a reaction, both from the public and even some of the officers who were constantly tasked with keeping him from unlocking new ways to freedom.

Alex Geddes, the operations manager at Peterhead Prison Museum, expressed admiration for the personality, who had songs written in his honour which are still performed today by folk groups and symphony orchestras.

He told me: “There are so many strands to the man it’s almost difficult to know where to start.

“He escaped several times from Peterhead, then he became known as a wartime hero and he established links with some of the locals who had served with him in the conflict.

“His two great-grandchildren came up here to see the Scottish escapologist get free from chains, padlock and a locked cell to celebrate Harry Houdini.

“He was given 30 minutes to get out of everything and he did it in just over eight minutes.

“It’s simply another illustration of how he had this amazing capacity to solve puzzles and mysteries and work out all these intricate details.

“There is a lot of interest because he was such a complex individual. And his legend lives on.

“We have plenty of visitors who want to hear more about him.”

Age was gradually catching up with Ramensky as the 1960s loomed and there were no more great escapes after he was incarcerated again at Peterhead.

But many issues remained unresolved from his break-out in December 1958.

How had he managed to avoid the police for nine days and nights in such wintry conditions?

Where did his food come from?

Was there an accomplice or had he used his Commando skills to remain on the run?

‘He canna live on neeps for nine days’

Charles Buchan, one of his wartime colleagues, said later he doubted it would have been possible for him to stay hidden in the north east without any help.

But he added: “It was part of his training as a Commando to live off the land.

“Cases are known where Commandos were dropped at John o’ Groats, penniless and without food, and told to make their way to Land’s End.

“If he was determined enough, he could live on two slices of bread and a glass of water a day. And we know that Ramensky is a very determined man.”

Others were more sceptical. As one local resident told the P&J: “He must have been holed up somewhere. He canna live off neeps for nine days!”

However, despite the plaudits he gained for his nerveless demeanour amid the hostilities, Ramensky did not give up his safe-cracking lifestyle.

He spent most of his time after the war in and out of jail, eventually dying in Perth Royal Infirmary in 1972, after suffering a stroke at Perth Prison.

Even in his late 60s, when he might have been collecting his pension and thinking about winding down, he was otherwise engaged, serving a one-year sentence after being caught on a shop roof in Ayr.

Why was he there? Because, as he admitted, it posed another challenge for him and even though he was rumbled and arrested, he never relinquished his passion for breaking and entering.

During his wartime service, Ramensky was known to have sent various items looted from German and Italian targets to friends and associates in Scotland.

He might have died at 67 without ever imagining that, nearly 50 years later, his feats would be commemorated in one of his old prison patches.

But his funeral was packed with mourners, including many representatives from law enforcement across Scotland and, in a world where criminals and violence usually went hand in hand, he was something very different.

As the three boys who met him that chilly December day have testified.