Not too many footballers become so synonymous with their team that supporters change the name of their club to the player himself.

So you can probably guess at the impact which Fifer Billy Liddell made on Anfield aficionados that, even while he became one of the greatest names in the club’s history during decades of service from the 1930s to the 1960s, the singular cry reverberated around the ground: “Liddellpool, Liddellpool!”

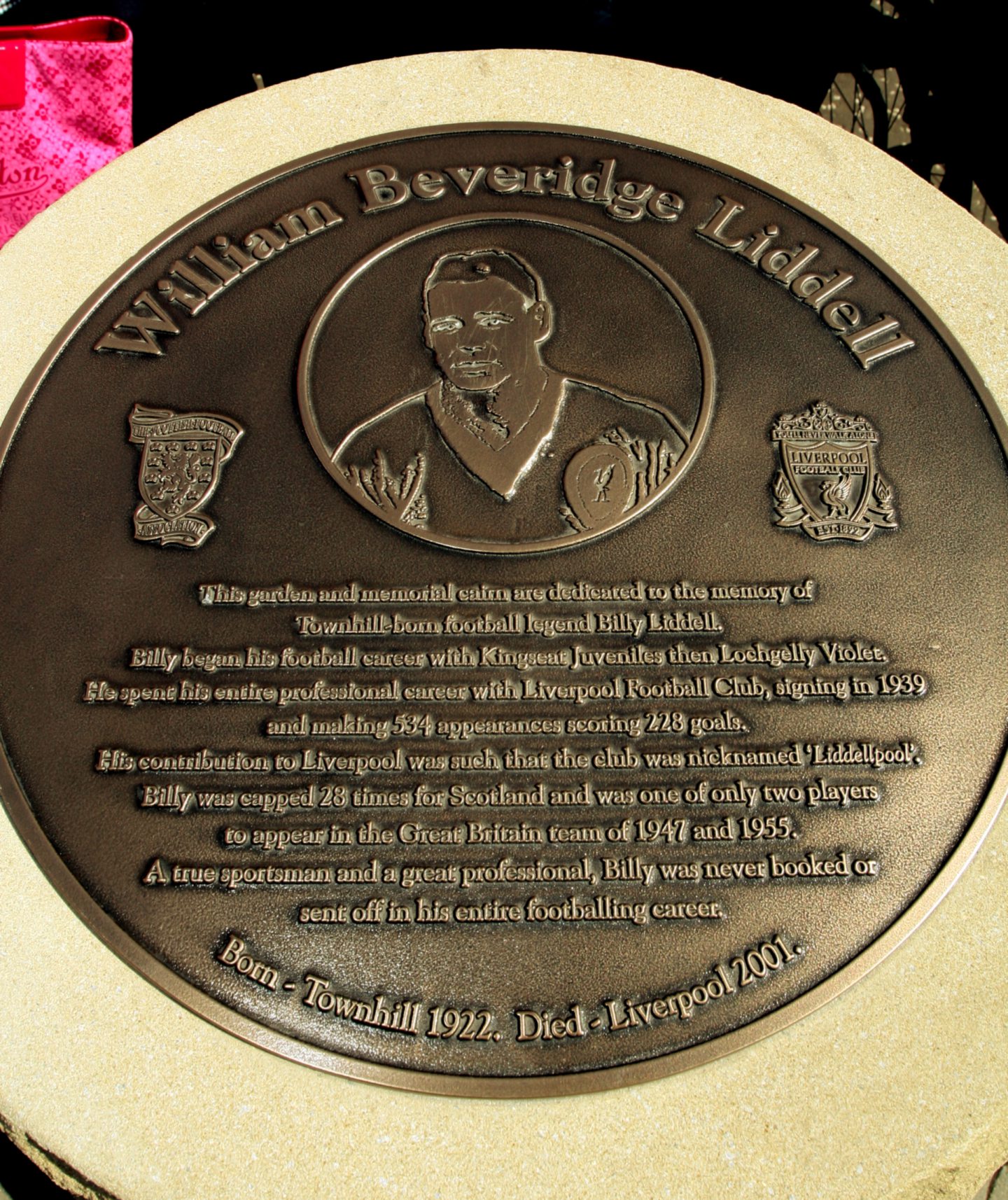

This fellow, brought up in Townhill and Dunfermline, wasn’t just a proud Scot with a steely desire and determination to drive himself forward, but a true gentleman of the sport, who was never booked or sent off in his career, abstained from alcohol and found other ways to express himself than by resorting to what is euphemistically known as ‘industrial language’.

Even when assigned a navigator’s role in the RAF during the Second World War, Liddell remained true to his religious beliefs.

There was a job to be done, a conflict to be won, but that didn’t mean he had to swear blue murder, hate the pilots in the enemy aircraft or hope other humans were killed.

He was a special character and, 100 years after he entered the world on January 10 1922, it’s time to revisit the achievements of a genuine nonpareil.

The bare bones of the story are remarkable enough in conveying how William Beveridge Liddell played his entire professional career with Liverpool after signing with the club as a teenager in 1938 and staying there until his retirement when he was nearly 40 years old in 1961.

He not only scored 228 goals in 534 appearances, but became the beating heart and pulse of the team at a stage long before the arrival of Bill Shankly, often dragging his colleagues up from the doldrums through the sheer force of his personality and the irrepressible manner in which he performed.

Liddell was a pearl in the dross

Liddell won a league championship in 1947, featured in the club’s 1950 FA Cup Final defeat by Arsenal and gained 29 Scotland caps, despite Liverpool languishing in the second tier of the English game for much of this period.

There were plenty of offers to join other more successful organisations, both in England and further afield including as part of a rebel circus in South America, but he dismissed them with the insousiance he regularly displayed towards opponents as he weaved his magic, reduced them to stupefied befuddlement and left them clutching at shadows.

But don’t just take my word for it.

As a new book Liddell at One Hundred reveals, he may have died in 2001, but he is still revered at Anfield and viewed in the same illustrious bracket as the likes of Kenny Dalglish, Emlyn Hughes, Graeme Souness and Steven Gerrard.

Jamie Carragher is among those who have no doubt about the refulgent qualities and tough-as-teak resolve which his predecessor possessed.

He said: “Any fans today who are not aware of Billy just need to know that the Liverpool team was known as Liddellpool and that shows the impact he had.

“It’s very difficult to get footage or to study too much of that era. There are probably very few players remembered from that time, it was so long ago, and Liverpool were not as successful before Bill Shankly arrived [in 1959].

“It almost feels like there is a line in the sand with Shankly and we forget what went before. But you will see a lot of people pick their all-time Liverpool XI and Billy will find his way into a lot of the teams and is hard to ignore.

“You admire these players more. Yes, they have won fewer trophies and medals than others, but actually staying there when it’s not going so well shows loyalty when you are a top player.

“I think that is why Steven Gerrard is respected so much, not just in this country but around the world, because he stuck with his team through thick and thin. Liddell did the same. And Liverpool FC was his club.

“There are seven players that have benches named after them at Anfield and the fact Billy is in that group shows how highly he is regarded by everyone at the club.

“Anybody who has still got a banner on the Kop 50-60 years after they have stopped playing….they must have been some player.”

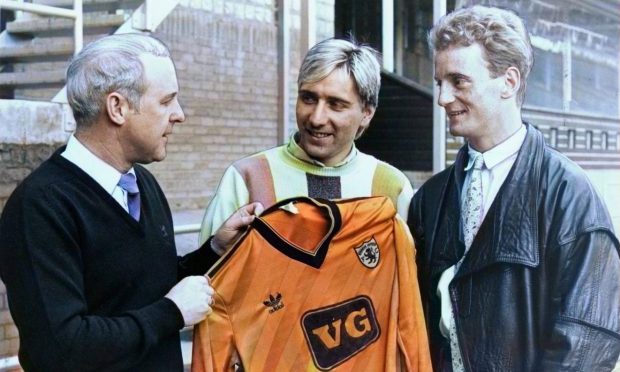

Similar tributes have been lavished on Liddell by football figures from different generations including Liverpool and Scotland maestro, Hansen, and Aberdeen-born George Scott, who was described as the “lost Shankly boy”.

Hansen was among those who benefited from the wit, wisdom, prescience and planning of the redoubtable Shanks, but, as he has said in Peter Kenny Jones’ book, it was the behind-the-scenes chats and encouragement of the ubiquitous Liddell which helped to provide him with a lift when he journeyed down to Anfield from Partick Thistle in the late 1970s.

‘He always said: ‘You’re doing well’

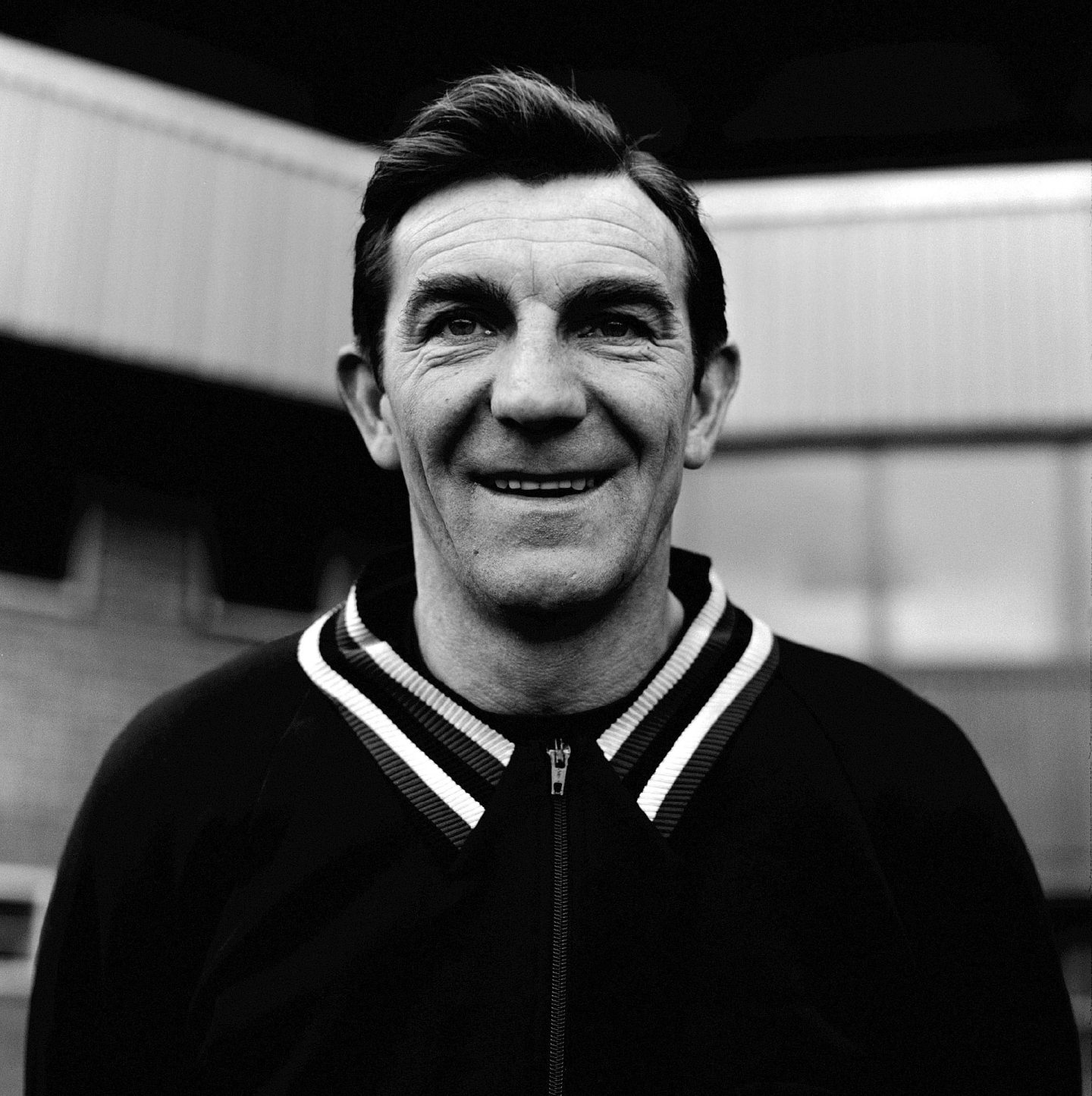

Hansen recalled: “The first time I met Billy, I knew him only by the reputation of being one of the best footballers of that time who had played for Liverpool, probably the best.

“What really surprised me was his demeanour. He was the friendliest and most approachable guy I think has ever been at Liverpool.

“Billy was beyond friendliness: he was just awesome. Always smiling, always ready to speak to you, always engaging and he was just brilliant, absolutely brilliant.

“His wife, Phyllis, was a real character as well. He was quiet, but she was more outgoing and the two of them were a perfect partnership.

“He was a part of Liverpool’s heritage, a fixture of the club, and everybody loved him. He never got above himself; he was always on an even keel and a delight to talk to.

“He would always say to us that we were doing well. It didn’t matter if you were terrible, Billy would say: ‘You’re doing well’. The fact he has been immortalised with a bench by the new Main Stand is a testament to what he did while he was at Liverpool. When you listen to the stories and read all the reports, it’s clear that he was right up there with the best of them.”

Liddell, who emerged from a working-class environment, and initially studied accountancy, was snapped up by Liverpool manager George Kay, who became interested in signing him on the recommendation of the club’s Scottish half-back – a certain Matt Busby – who subsequently developed into one of the most fabled figures at Manchester United.

But, although Liddell had to intersperse football with war service and turned out for several clubs during his military service, including Dunfermline Athletic – he was a pivotal figure during a 5-1 victory against East Fife in November 1944 – his heart was forever with Liverpool as he proved for 15 years after the conflict was over and he was able to return to Anfield.

Scott speaks so highly of him

George Scott said: “Billy had time for everyone, considering what he had achieved, which was everything in the game.

“Shankly told us all at the beginning that the club was called Liddellpool. He carried that team, there were some good players, but he was the main man.

“I would still say that he was one of the top three players Liverpool ever had.”

Another of his compatriots, Dundee star, Doug Cowie, who died at 95 towards the end of 2021, also lent his voice to the Liddell legend.

He said: “He had the type of build that he looked strong and speedy. You thought, just by looking at him, that he had a good chance of pushing the ball past the full-back and beating him for speed and that was really his game.

“He was direct. Rather than looking for short passes inside, he was more likely to get up the line and whip the ball across for his team-mates or cut inside for a shot at goal – and he could do either.”

In short, he was a dangerous player, whether as creator or striker – a modest, God-fearing man with the capacity to put the fear into any rival in his path.

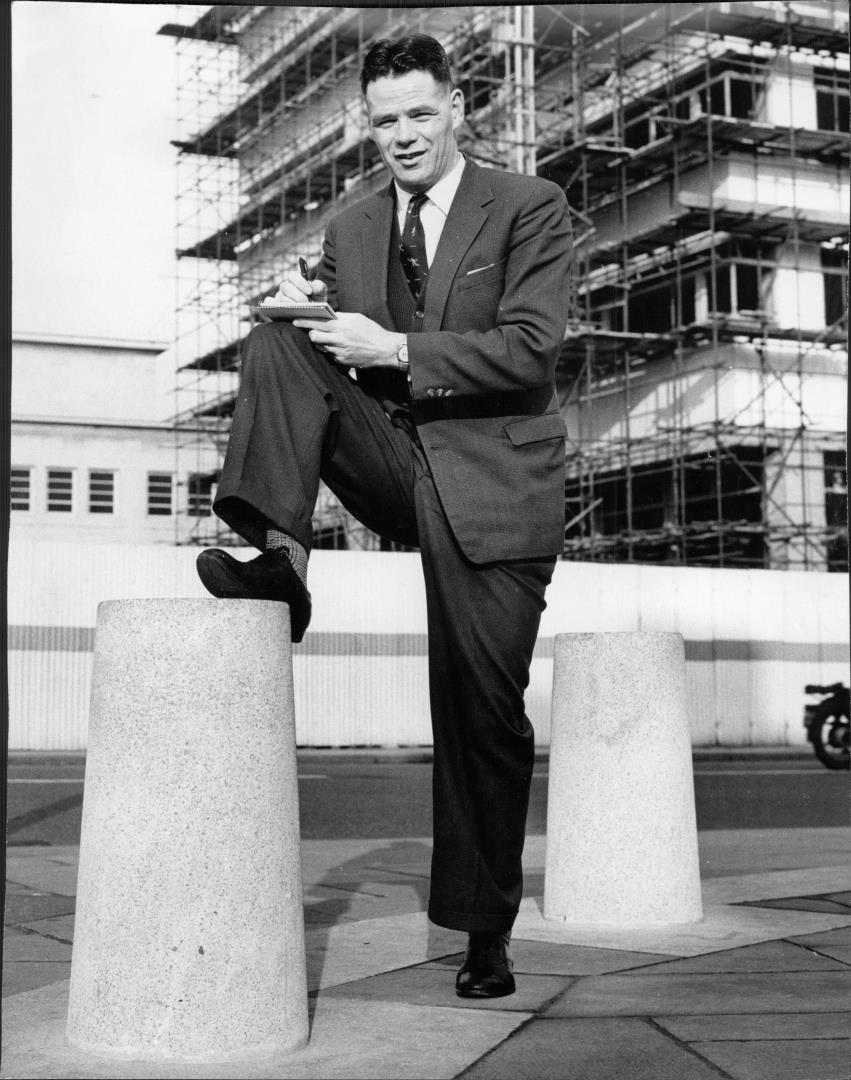

After his retirement, Liddell settled in Liverpool with Phyllis and their twin sons, and he was happy to continue living in Merseyside with his family. While still a player, he was appointed a Justice of the Peace for the city in 1958 and he contributed a column to the Echo’s football edition.

He became occupied with doing as much voluntary work as he could, which entailed him being an occasional disc jockey for the Women’s Voluntary Service at Alder Hey Children’s Hospital, working for local youth clubs, and teaching at a Sunday school.

He was friends with Ken Dodd, Morecambe and Wise writer Eddie Braben, actress Anna Neagle and Frankie Vaughan.

A man of all people

Indeed, he was friends with almost everybody he met, regardless of age, background or football favouritism.

Liddell subsequently accepted the role of chairman of Littlewoods’ Spot the Ball panel and was president of the Liverpool FC Supporters Club.

Yet, after being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in the early 1990s, this bright, intelligent, affable individual gradually went downhill into oblivion.

But that doesn’t diminish his legacy. Posthumous recognition has included a plaque unveiled in 2004 at Anfield and sixth place in a poll of Liverpool fans, conducted in 2006 under the title 100 Players Who Shook The Kop.

He was inducted into the Scottish Football Hall of Fame in 2008 and there is a popular sports centre in his birthplace of Townhill, which helps youngsters keep active.

He would have liked that. And Billy Liddell will never be forgotten.

Liddell at One Hundred by Peter Kenny Jones is available from Pitch Publishing.