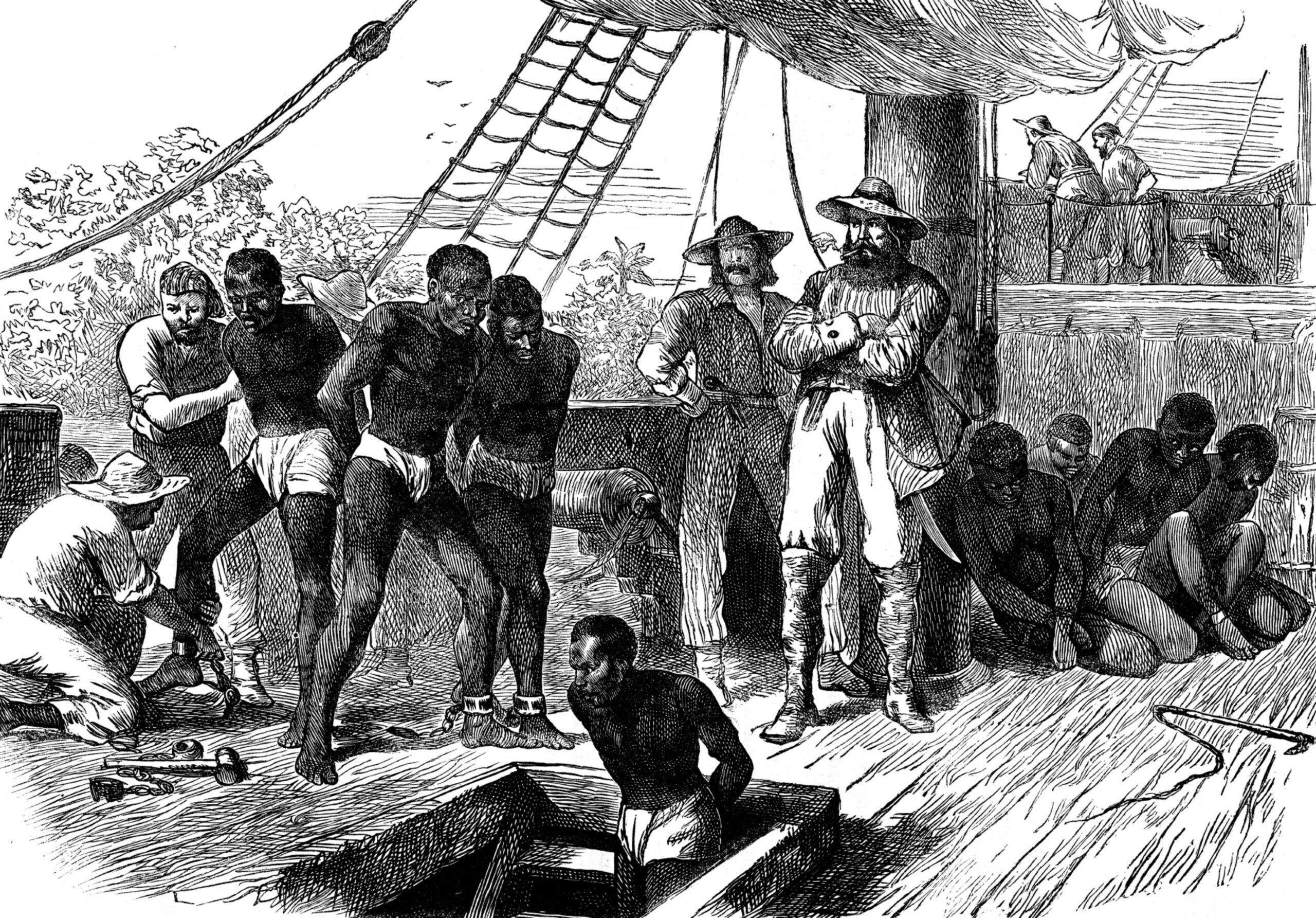

Although it’s a word from a bygone age, the controversy over the toppling of slave owner Sir Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol shows that slavery remains one of the most thorny issues in British history.

Every other week, or so it seems, there’s an institution or university in Britain which finds itself in the headlines for the wrong reasons, grappling with past connections to the trade which was eventually abolished in the 19th century.

And the news that the “Colston Four” have been cleared of criminal damages after toppling a statue of him into the river during the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 has reopened fresh arguments between rival groups.

Yet while the profits of slavery and its links to many of the country’s most famous places of culture, commerce and academia have left a grim legacy for current generations, it shouldn’t be forgotten that people were campaigning against it and actively calling for its abolition more than 200 years ago.

And one of the most vocal critics of what he regarded as an “odious” practice was William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, who grew up and was educated in Perth before moving to London at the age of 13.

This bright, beetle-browed fellow was accepted into Christ Church, Oxford in May 1723, and graduated four years later.

Then, returning to London from Oxford, he was called to the Bar by Lincoln’s Inn on 23 November 1730, and quickly gained a reputation as an excellent barrister.

However, that was not the reason why his name is preserved for posterity.

He impressed all his school tutors

Murray was born in 1705 at Scone Palace in Perthshire, the fourth son of the 5th Viscount of Stormont and his wife, Margaret.

Educated at Perth Grammar School, where he was taught Latin, English grammar, and essay writing skills, he later said that this gave him a great advantage at university, because those students educated in England had been taught Greek and Latin, but not how to write properly in their own language.

While at school, it quickly became apparent to his tutors that Murray was a particularly intelligent student and, in 1718, his father and older brother James decided to send him to Westminster School.

Soon enough, the youngster was making waves as one of the leading figures in the Age of Enlightenment. And if that meant ruffling the feathers of the establishment and disturbing the status quo, he was up for the challenge.

Murray is best known for his judgment in Somerset’s Case on the legality of keeping slaves in England; an issue which deeply troubled him.

The English – Scots were involved as well – had been participants in the slave trade since 1553 and, by 1768, ships registered in Liverpool, Bristol and London carried more than half the slaves shipped in the world.

James Somerset was a slave owned by Charles Stewart, an American customs officer who sailed to Britain for business in November 1769.

A few days later Somerset attempted to escape. He was recaptured and imprisoned on the ship Ann and Mary, which was owned by Captain John Knowles and bound for the British colony of Jamaica.

However, three people claiming to be Somerset’s godparents, John Marlow, Thomas Walkin and Elizabeth Cade, fought against his captivity, and Knowles was eventually ordered to produce Somerset before the Court of King’s Bench, which would determine whether his imprisonment was legal.

Murray reached a famous verdict

After the attorneys for both sides had given their arguments at length, Murray delivered his groundbreaking judgment 250 years ago in 1772 which ruled that a master could not carry his slave out of England by force.

He concluded: “The state of slavery is of such a nature, that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political; but only positive law, which preserves its force long after the reasons, occasion, and time itself from whence it was created, is erased from memory.

“It is so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law. Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from a decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore James Somerset must be discharged.”

This ruling earned banner headlines in many contemporary newspapers, but it was not an end to slavery by any means and only confirmed it was illegal to transport a slave out of England and Wales against his will.

The trade also persisted in the rest of the British Empire from Africa to the Caribbean, yet as a result of the reporting of Murray’s decision, some publications gave the misleading impression that it had been abolished.

However, historians believe that between 14,000 and 15,000 slaves were immediately granted their liberation in England, a large number of whom remained with their masters as paid or unpaid employees.

And, although slavery was not completely eradicated throughout the British Empire until more than 60 years later in 1834, the Scot’s decision is considered a significant step in recognising its illegality.

Dido Belle had her own story to tell

Murray wasn’t simply content to pass lofty judgments from on high which didn’t affect him directly. He actively helped in reforming racist attitudes towards non-white people in Britain and did so in his own household.

Dido Elizabeth Belle, a British heiress and a member of the Lindsay family of Evelix, was born into slavery and illegitimate in 1761; her mother, Maria Belle, was an African slave in the West Indies.

But her father, Sir John Lindsay, a British career naval officer who was stationed there brought the four-year-old girl with him when he returned to England in 1765, entrusting her upbringing to his uncle William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, and his wife Elizabeth Murray, Countess of Mansfield.

The Murrays educated Belle, bringing her up as a free gentlewoman at their Kenwood House mansion, together with another great-niece, Lady Elizabeth Murray, whose mother had died and the latter and Belle were second cousins.

The spirited woman, who refused to be stereotyped and whose remarkable life was brought to the silver screen in the 2013 film Belle, starring Tom Wilkinson, Miranda Richardson, Tom Felton, James Norton, Matthew Goode and Gugu Mbatha-Raw in the title role, lived there for 30 years.

In his will of 1793, Murray, who regarded her as somebody he was proud to have as a member of his family, conferred her freedom and provided a significant sum of money and an annuity to her, making her an heiress.

Samuel Johnson was referring to Murray when he made his infamous comment: “Much may be made of a Scotchman, if he be caught young.”

But this proud son of Perth surely deserves to be as well-known as the man of letters and dictionary renown.