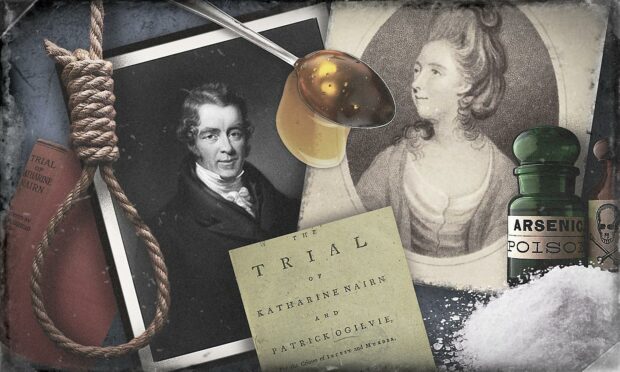

They fell in love – a forbidden romance, punishable by death. Then they committed murder, and one of them got away with it.

The other swung from the gallows in a lurid public execution, protesting his innocence.

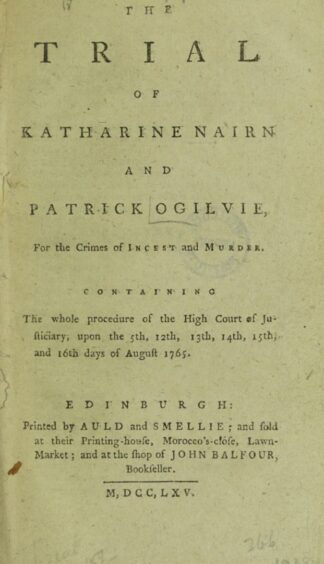

The trial of Patrick Ogilvie and Katharine Nairn was a cause célèbre in Forfar in 1765, sparking endless newspaper columns at the time, repeated the following century in comparisons with the infamous Madeleine Smith murder case in Glasgow in 1857.

It was revisited in 1926 when an entire book was written about the case, and the court proceedings were picked over in detail yet again in local press in 1954.

Now, almost 250 years later, the events continue to fascinate, albeit through a prism of vastly changed times.

The Ogilvie-Nairn marriage

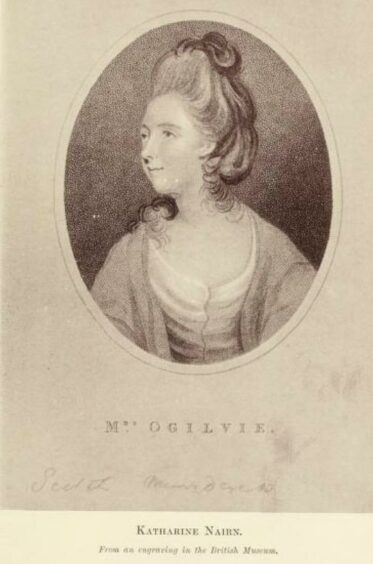

The story begins with the marriage of Katharine Nairn of Dunsinnan to Thomas Ogilvie of Eastmiln.

Katharine (spelled various ways, and she was also known as Kate) was the daughter of Perthshire baronet Sir Thomas Nairn, and Thomas Ogilvie was a bonnet-laird and small farmer, moderately well off.

The problem was that Katharine, described as beautiful and fascinating, was 21, and he over 40, in less than robust health.

Things didn’t look good for the arranged marriage to start with, but the minute Thomas’s brother Patrick came on the scene the die was cast.

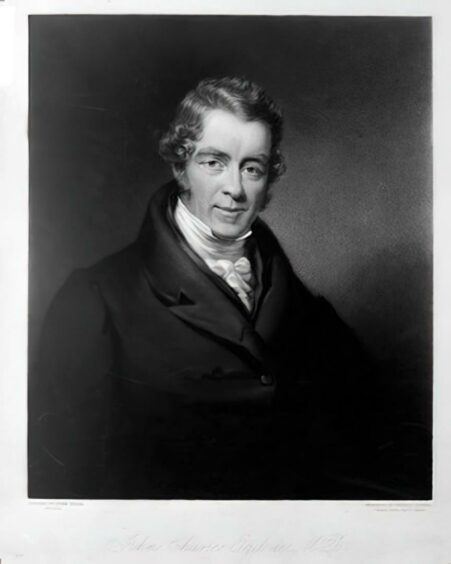

Patrick, a dark-haired, dashing lieutenant in the 89th (Highland) Regiment of Foot had returned to Scotland from the East Indies soon after the wedding, and moved back into the family home at Eastmiln.

It was like a lightning strike when he and Katharine clapped eyes on each other and the pair were soon lovers.

Incest was a capital crime

The problem was sex between a man and his sister-in-law was viewed as incest, and a capital crime under Scots Law in 1765.

They were pretty open about it too, writing letters to each other, meeting privately, leaving the bedroom door open in flagrante.

After four months of this, Thomas sent his brother packing, to the outrage of Katharine.

Love makes you do crazy things – Katharine and Patrick’s minds turned to murder.

Patrick went to see James Carnegie, surgeon, of Brechin, and bought a phial of laudanum allegedly for his health, and about half an ounce of arsenic, saying it was to kill some dogs which had destroyed game.

He then went to the home of his brother-in-law Andrew Stewart of Alyth, wrote to Katharine and sent over the phials with Stewart who had occasion to visit Eastmiln, only a few miles away.

He told Andrew the phials were for Katharine, and that he should deliver them privately to her.

This he did, and she locked them in a drawer immediately, without reading the accompanying letter.

Thomas warned of suspicions

Andrew had his suspicions, as he warned Thomas Ogilvie not take any meat or drink from his wife unless there were others partaking of it.

He declared in court that Katherine had told him she wished her husband was dead.

The next day, June 6, Thomas missed breakfast, being still in bed, so Katharine took a bowl and filled it with tea, saying she was going to take it up to her husband.

According to witnesses in court, she went into a closet adjoining the bedroom and mixed the poison into the tea, also stirring in honey to disguise the taste and stop the powder from settling on the bottom.

Thomas took the tea, and got on with his life for the next hour until he started retching, vomiting and convulsing.

He called for water to drink, and when it was brought in in a bowl by his maid, he said: “Damn that bowl for I have got my death out of it already,” and told her to bring up water in a tea kettle.

His sickness progressed for several hours, and Katharine refused to call the doctor, even when pressed by Andrew Stewart.

Doctor called, but too late

Eventually, near sunset, she sent for Peter Meik, surgeon at Alyth, but it was too late.

Thomas died before he arrived.

Katharine must have been banking on his death being blamed on his previous indifferent health, as she was shocked when a few days later she found out they were going to inspect the body.

She knew the presence of arsenic could be found out at the point, and cried out, “What will I do!”

In fact a post-mortem was never carried out due to the hot weather.

Patrick was now heir to Eastmiln, and returned to oversee his brother’s funeral.

Katharine had been indiscreet the whole way through her escapade, confiding her intentions to Ann Clark, a relative of Thomas’ who lived in the same house, and whom he seemed to dislike.

It was Ann who warned Andrew Stewart about the poison, and who went on to inform Thomas’s younger brother Alexander of her suspicions.

Katharine Nairn and Patrick Ogilvie arrested

Alexander activated the law, and soon Katharine and Patrick were arrested.

The trial took place that August in the High Court in Edinburgh.

Ann Clark and two of Thomas’s servants were held in the Castle ‘that there might be no obstruction to the course of public justice’.

A theory that Ann and Alexander had cooked up a plot to kill Thomas to hasten Alexander’s inheritance of the estate was largely dismissed.

Patrick’s regimental comrades stuck by him, refusing believe in his guilt and bringing him a violin which he played mournfully in jail.

More than 100 witnesses were rolled out in court, but proceedings didn’t go well.

Shambolic behaviour of the jury

The jury was described as comporting themselves in a ‘free and easy manner’, of being drunk and leaving the court to talk in private with various people, particularly the counsel for the prosecution.

A bombshell was dropped when Katharine declared herself pregnant, and a number of midwives were called in.

They couldn’t say whether she was pregnant or not, so her case was deferred for three months to late November.

Eventually the jury found the pair guilty of incest, Katharine guilty of poisoning her husband and Patrick also guilty for his role.

“It fell upon the ears of the prisoners with appalling horror,” reported the press. “Katharine Nairn uttered a loud scream and fell back in a swoon.

“Patrick Ogilvie turned pales as death, groaned audibly and caught at the rail of the dock for support.”

Patrick is hanged

Patrick’s hanging took place, after four short reprieves, on November 13 in public in a crowded Grassmarket.

Even that didn’t go well – on the first attempt the noose slipped when the executioner threw him off the ladder, and he fell to the ground.

Resisting, and continuing to protest his innocence, he was dragged up again and finally met his maker.

Meanwhile Katharine was indeed found to be pregnant, and delivered a baby girl on January 27 1766.

Knowing that she couldn’t put off the scaffold for long, she contrived to disappear from the Tolbooth like a puff of smoke some three weeks later.

Katharine flees jail

Her family is believed to have bribed the turnkeys and she fled dressed as an officer, ‘very thin and sickly, muffled up in a greatcoat’, attended by an old family retainer.

The baby was left in the Tolbooth, where she sadly died some two months later.

Despite 100 guineas promptly placed on her head, Katharine managed to make it to France, where different versions of her fate floated about for years afterwards.

Some said she spent the first months of her freedom in Dublin, passing herself off as a man.

Others said she made it to France where she took refuge in a convent in Lisle, ‘a sincere penitent’.

Another account said she was wooed by a respectable French officer, who married her even after she told him of her past, and they lived happily together.

But the press would have none of that: “We rather think the latter version has a touch of romance in it. The convent was most likely to be the last asylum of this wretched woman.”

More true crime from Past Times:

Inverness murder trial: Dying woman crawled from gory scene after husband slit her throat

When three Aberdeen boys helped capture criminal, escapologist and war hero Johnny Ramensky