It was one of the most notorious crimes of the Victorian era and it led to a man spending more than 40 years in prison in Peterhead and Perth, even though there were serious questions about his conviction.

Some criminologists, who have examined much of the often sketchy evidence, are still unsure whether John Watson Laurie, who was convicted of murdering Edwin Rose on the Isle of Arran in July 1889, was guilty of the act or whether it was an accident or a robbery that went tragically wrong.

The contemporary accounts of the case, involving some reports in the Aberdeen Journal and The Courier, covered the court proceedings as if the press were acting as judge, jury and executioner on the Crown’s behalf.

And, despite Laurie consistently arguing that he was innocent of everything but robbery, he ended up only just escaping the gallows as the prelude to serving the longest prison stretch in Scottish history.

Innocent excursion

The grim proceedings began in prosaic circumstances when Edwin Rose, 32, who was employed as a clerk in London, was travelling on the steamer from Rothesay to the Isle of Arran for a holiday and a rare chance to relax.

While relishing the picturesque journey, he met 25-year-old Laurie, a pattern-maker from Glasgow – who was travelling under the name of John Annandale – and the Scot invited Rose to share his lodgings on the island.

The pair subsequently forged a friendship with two other young men in the following days and the quartet went boating and walking together.

It seemed as if it would turn into an idyllic vacation in a tranquil setting during a glorious summer. There was no hint of the horror that lay in store.

However, Laurie had proposed to Rose that the two of them should join forces to climb Goatfell, the highest point on Arran at an imposing 874 metres and one of the most striking natural features on the island.

It should have been the perfect viewpoint for the duo to gaze across the island and out to sea. But one of the other men warned Rose to be on his guard against Laurie and discouraged him from venturing on the climb.

He and his colleague then departed the island on July 14, at the conclusion of their holiday, and early the next morning, Rose and Laurie left their lodgings without saying where they were going.

Their landlady assumed they had absconded to avoid paying their bill and contacted the police. In just a few days, matters started to go very wrong, very quickly.

Rose’s brother arrived on the island on July 27 and told the locals that he had become concerned after his brother had not returned from his break.

He soon discovered details of the Goatfell excursion and, horrified at learning there was no news of either man returning from the trip which had happened nearly a fortnight earlier, immediately raised the alarm.

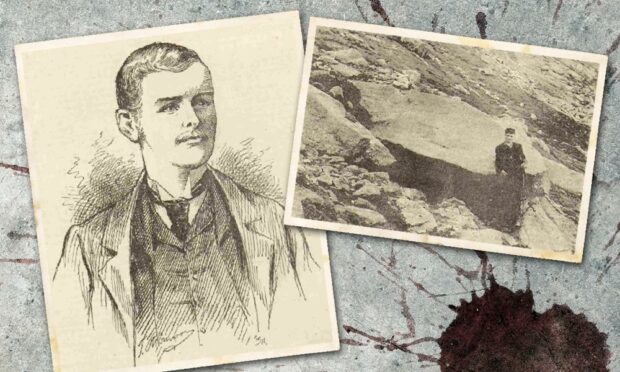

His concerns sparked an intensive search, involving more than 200 islanders, and they quickly found Rose’s body hidden under a pile of rocks.

It was later claimed “he had been beaten to death and robbed”.

Then a local shepherd emerged with the revelation he had observed Laurie descending Goatfell alone on July 15 – though he didn’t bother telling anybody at the time.

When details of the killing reached the newspapers, Laurie could hardly have behaved any more suspiciously. He quit his job and moved to Liverpool.

Next – and this was utterly inexplicable behaviour in the circumstances – he wrote to several newspapers to inform them: “I smile when I read that my arrest is expected hourly.”

But still justice crawled towards his capture.

The ‘facts’ were hard to pin down

Indeed, it wasn’t until September 3 that Laurie was spotted boarding a train at Ferniegair, a small village near Hamilton in Lanarkshire, and he was chased on foot by a local constable.

It was a dramatic state of affairs for the locals who flocked to the scene and, once he had been trapped in a local wood, he tried to cut his throat. But Laurie failed in that objective and the police apprehended their man.

This was the build-up to what turned into a very one-sided court case in Edinburgh, where Laurie was described by the prosecution as being a “common criminal” who had shown no remorse for his actions.

He did admit to robbing the hapless Rose, but passionately denied killing him, contending that the victim had perished as the result of a fall.

And yet, given his failure to provide any explanation for why he had been travelling incognito, fled the scene of the crime and failed to report the death of his colleague to the authorities, his defence was mercilessly ripped apart.

Given the fashion in which the trial was conducted, nobody should have been surprised when Laurie was found guilty and sentenced to death.

The sentence was commuted to life imprisonment after he was found to be of unsound mind. But that was only the beginning of decades of incarceration.

He was in jail as monarchs came and went, throughout the Boer War and the First World War, and as the Labour Party was formed and later became the government in Britain, yet Laurie knew nothing of these seismic events.

By the time he died, in 1930, he had served nearly 41 years in prison – but did he actually commit the offence that led to his captivity?

Evidence was purely circumstantial

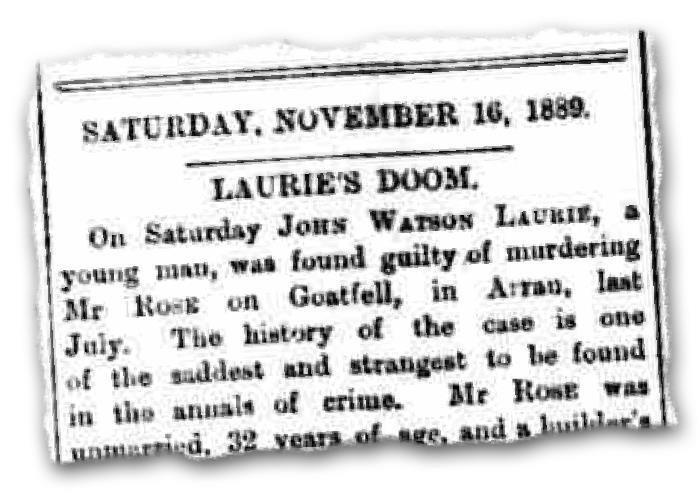

The Dundee People’s Journal reported on Laurie being sentenced to death in its edition of Saturday November 16.

It stated – this was comment, not reportage: “The history of the case is one of the saddest and strangest to be found in the annals of crime.

“Mr Rose, according to the testimony of his employer, was a most worthy young man, upright and righteous in all his conduct. All who came in contact with him spoke of his affability, his frank, agreeable and cheerful disposition.

“(When they climbed Goatfell), Laurie walked in front, while Mr Rose stayed behind and chatted freely with a party of other climbers.

“Rain having come on the party, and being without waterproofs, they took shelter behind a boulder, while the two men continued their ascent.

“They were overtaken at the summit, but were never seen together again.”

This was one of the most notable aspects of the coverage: the way in which Laurie went from being a “decent chap” to a man with a “devious mind”, although there was no clear motive for the alleged crime.

The claims that Rose had been brutally assaulted and thrown off the mountain were never substantiated.

On the contrary, his injuries were consistent with an accident sustained on the hills – but it was the behaviour of the accused that was highlighted, oblivious to his constant denials that he had taken items from Rose but not laid a finger on him.

The Courier summed it up thus: “After a trial, extending over two days, Laurie has been found guilty. The jury were not unanimous in their verdict, but we believe the public will endorse the opinion of the majority.

“The case was one of unusual difficulty, the evidence being purely circumstantial in all aspects. There was some room for the suggestion that Mr Rose might have met his death by accident and the defence advanced the theory that he fell headlong over a rock.

“But they failed to make good their theory and the balance of probabilities is in favour of the case put forward by the Crown. The only motive that can be suggested for the deed is the incredibly mean and paltry one of a vain desire to get possession of the clothes of the murdered man.”

And that was it. Laurie’s original death sentence might have been commuted to life imprisonment, but neither motive nor means was ever established.

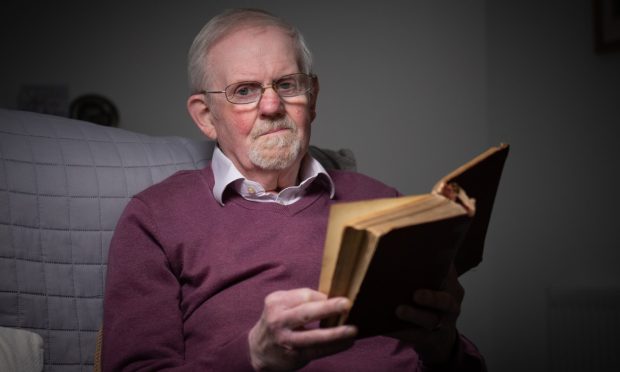

Alex Geddes, the operations direction at Peterhead Prison Museum, is among those who are left wondering if this might have been a miscarriage of justice.

He said: “This is another fascinating case from the past and I wonder what might have happened if the police had been granted access to the wonderful world of forensics that we have today back then.

“Based mainly on circumstantial evidence and with a frenzy of media coverage during the trial, it makes me wonder whether this was trial by public opinion rather than fact.

“But then, of course, hindsight is a great thing, as is the advancement of science and the impact it has had on murder investigations in today’s world.”

One last, sad postscript

Laurie’s letter to the papers, written in 1889, was actually posted from an address in the Granite City, as he continued to travel round Britain.

The Press & Journal reported: “The supposed perpetrator of the Arran murder, John W Laurie, was last week traced to Aberdeen.

“In his letter to a newspaper in Glasgow, he wrote: ‘I read so many mad and absurd things in the daily papers that I feel it is my duty to correct them.

“Although I am entirely guiltless of the crime that I seem to be very much wanted for, I recognise I am a ruined man, so it is far from my intention to give myself up. I hope this will be the last that the public hear from me.”

Within just a few months, he was back in the north-east, in Peterhead jail.

At which point, his fears were well and truly realised and he became a prisoner for the remainder of his existence.

He died in 1930 in Perth; having served 40 years and 11 months, the longest period anyone has ever been incarcerated in Scotland.

More like this:

Screw: How Peterhead Prison was used to film new Channel 4 series

When three boys helped capture criminal, escapologist and war hero Johnny Ramensky