James Leslie Mitchell couldn’t have imagined, while he was walking through the fields of north-east Scotland, that he would join the pantheon of the great literary figures.

After all, he was a shy young fellow who grew up on a small farm in Aberdeenshire, where he developed a love of books and was encouraged in his studies by his schoolmaster and the minister of Arbuthnott as the prelude to attending Mackie Academy in Stonehaven.

Years later Mitchell dedicated his exhaustive analysis of the history of the Mayan civilisation to his headmaster, Mr Alexander Gray of Echt.

But it was neither this, nor his time spent with Aberdeen Journals as a teenager, nor his period as an airman and soldier who visited India, Egypt and Persia (now Iran), which has ensured his work will live on forever.

Because this man Mitchell wrote under the name of Lewis Grassic Gibbon and, in 1932, published his novel Sunset Song, which is now regarded as one of the crown jewels in literary fiction.

And, on its 90th anniversary, it’s time to celebrate its Doric heritage.

It’s a work that is regularly voted Scotland’s favourite book in public polls, is acclaimed across the world, and remains the most evocative piece of prose ever penned about the Mearns with its message that people will come and go, laugh and cry, live and die, but only the land endures.

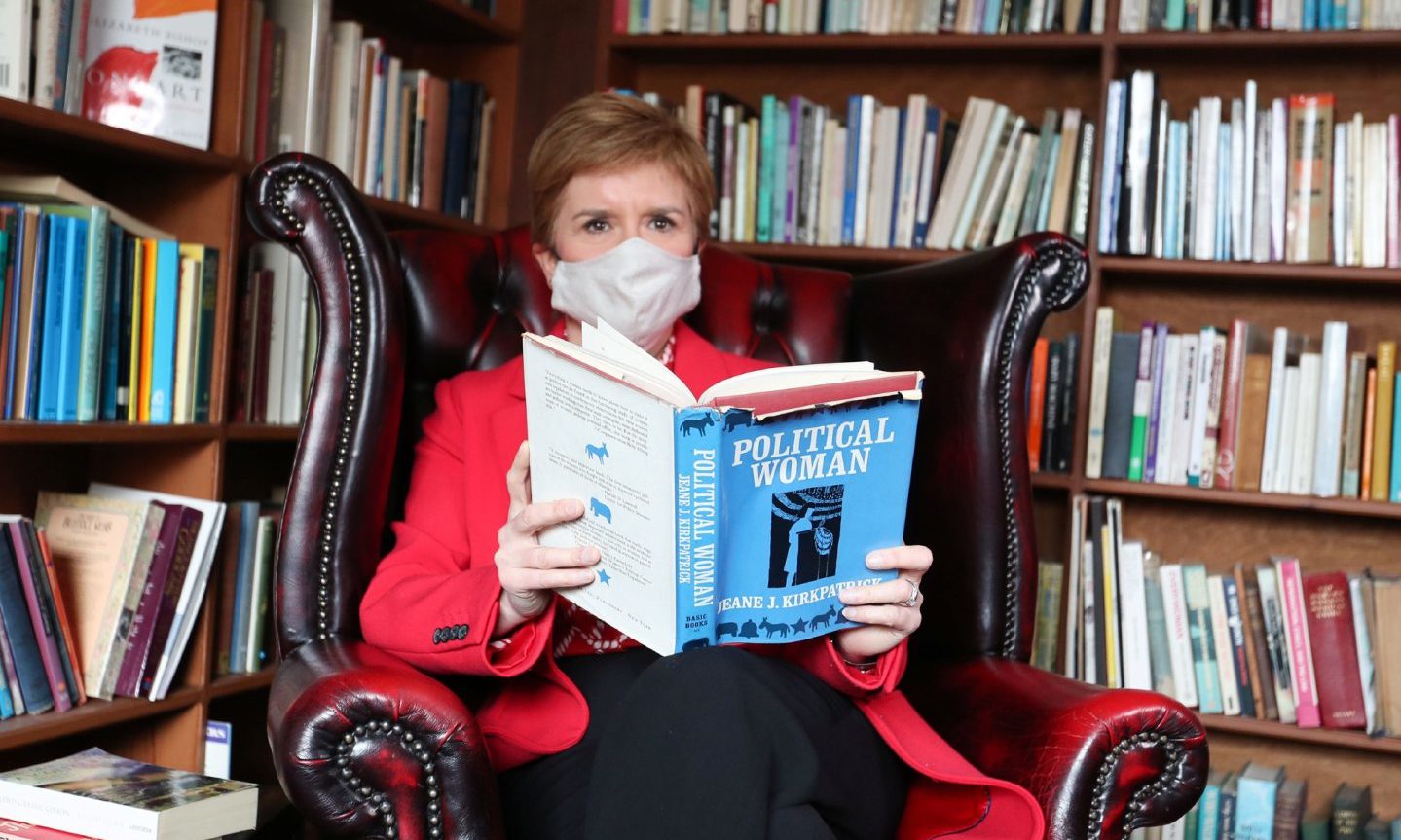

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon is among those who have spoken passionately about how its message has made a significant impression on her life.

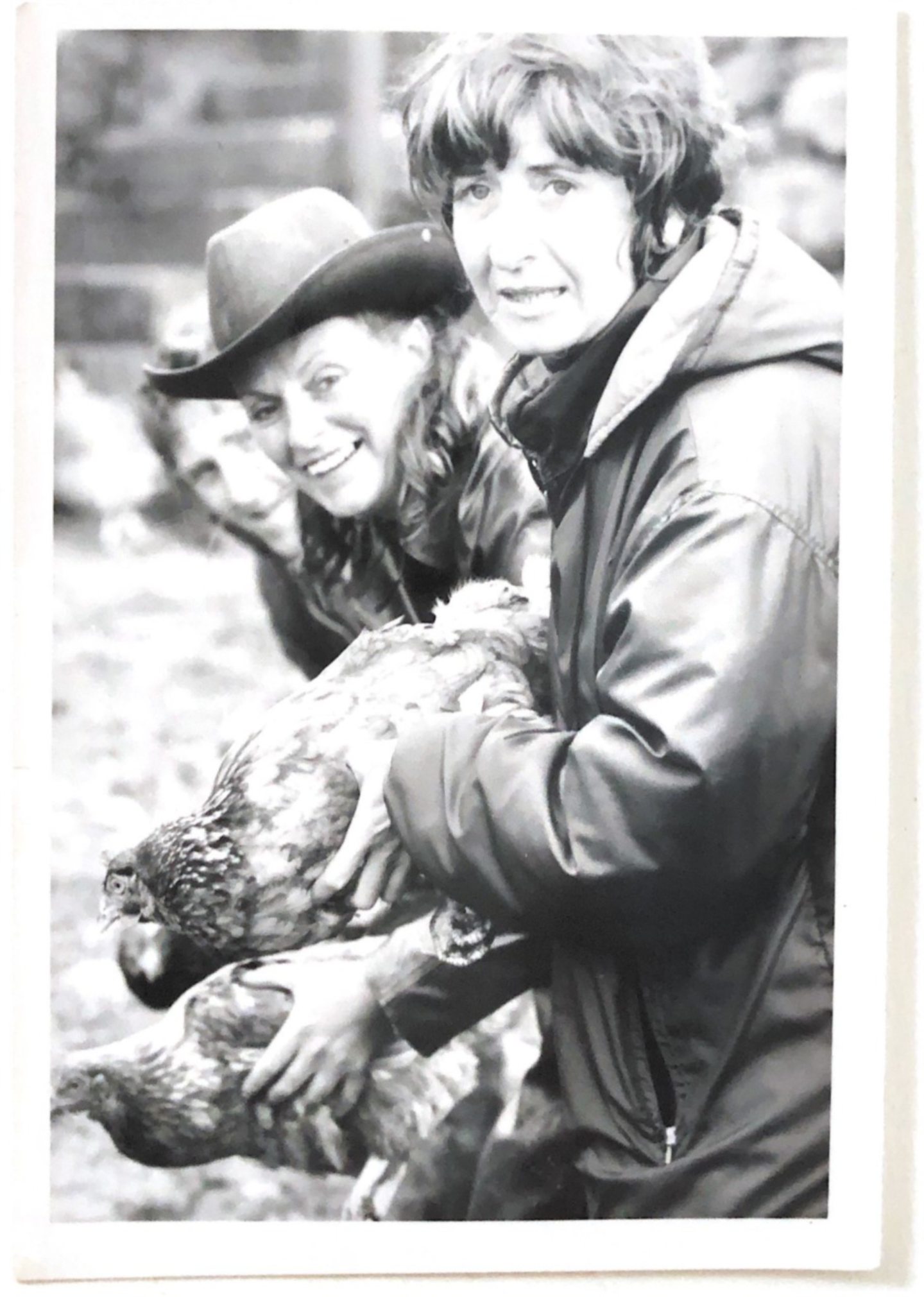

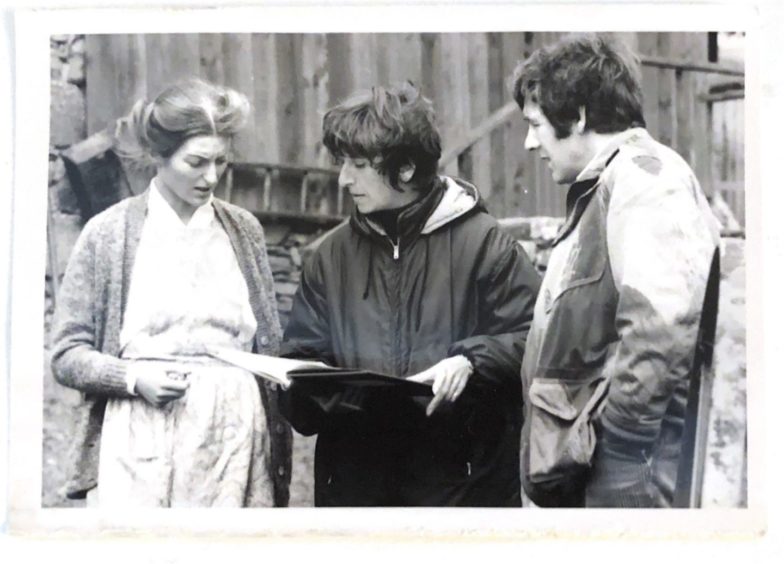

And anybody who watched television in Scotland in the 1970s will recall Vivien Heilbron in Bill Craig’s adaptation of the Lewis Grassic Gibbon novel, which was brought to the big screen by acclaimed director Terence Davies in 2015 with Peter Mullan, Agyness Deyn and Kevin Guthrie in the lead roles.

Grassic Gibbon died in 1935, at the age of just 33, from peritonitis, brought on by a perforated ulcer. But he has left behind an indelible legacy.

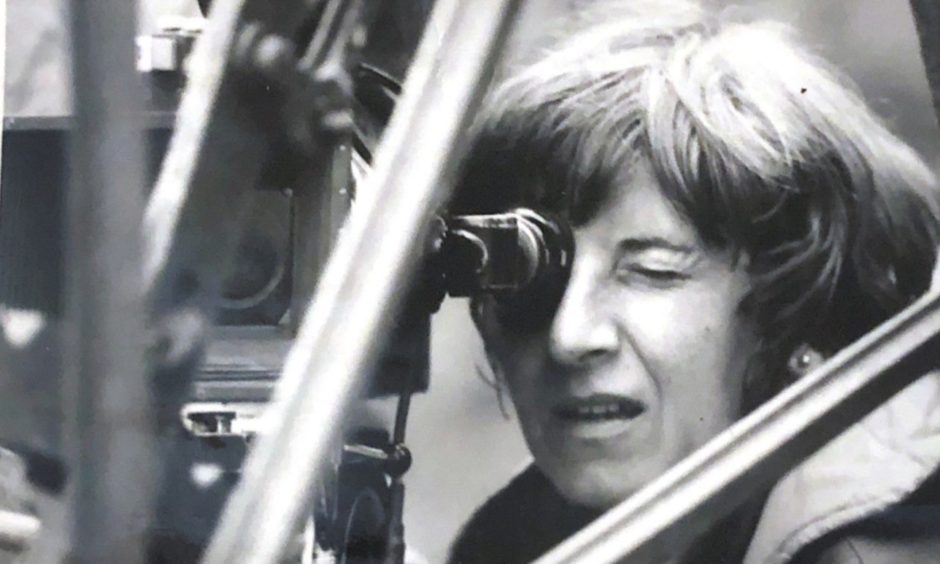

The handsomely-shot movie version gained mixed reviews but the TV series, much of it filmed on location in the Mearns and around Aberdeenshire, and directed by Moira Armstrong, was a very hard act to follow.

As the heroine Chris Guthrie, one of the strongest female characters in the world of literature, Vivien Heilbron was tough and she was tender; feisty and flirtatious; intelligent and intuitive.

The book and their heroine deserve their place in history.”

Vivien Heilbron

She was confronted with tragedy and faced the worst kind of travails within her own household where there was no escape from her domineering and predatory father.

Yet while her family and friends were dragged away from the fictional parish of Kinraddie to endure their own privations in the trenches of the First World War, Chris stuck to her philosophy that the countryside will prevail.

To that extent, she wasn’t just a powerful woman at the heart of an emotional drama. She was Mother Nature herself.

Heilbron said in one interview about the start of her career: “I went from playing an aristocratic German countess to appearing as this Scottish peasant girl so it was a big contrast, but it turned into one of those productions where everything came together.

“I was from Glasgow so I had to learn to speak the (Doric) language, because it was so important, but some of the cast were from the north-east and they helped me in every way they could.

“It’s a long time since I played Chris (she returned in the second and third parts of the trilogy, A Scots Quair, Cloud Howe and Grey Granite as the ’70s progressed) but she was such a fascinating character.

“Chris has to be this big mass of contradictions: she goes through all these different emotions of love, loss, anger, humour, darkness and rebirth and we see her develop from a young woman into adulthood.

“The book and their heroine deserve their place in history.

“There is no better description of the way all these young men from small villages went off to fight in a war, which the majority of them didn’t understand, and from which so many never returned.

“That is one of the reasons why it carries so much resonance.”

As a Fellow of the Shakespeare Institute at Stratford, Heilbron has travelled all over the world.

She has heard praise for Sunset Song wherever people are tilling the land and striving to make their way on the soil.

As she said: “There is a universality about Sunset Song which strikes a chord in so many different places.

“I remember talking to somebody in Greece many years ago and he was raving about the book and I asked him why.

“He replied: ‘It tells the story of peasants the world over’ and I understood exactly what he meant.

In no small way, I owe my love of literature to Sunset Song.”

First Minister Nicola Sturgeon

“What was wonderful was that Grassic Gibbon was very specific about the countryside, the people and the language of the Mearns, but his message wasn’t remotely parochial.

“On the contrary, there was a timeless quality to what he wrote, which is why he is remembered and held in such high regard.

“He died too soon (in Welwyn Garden City in Hertfordshire), but he was responsible for creating a masterpiece which will live forever.”

Nicola Sturgeon echoes these views, to the extent it is No 1 in her literary list.

She wrote an effusive introduction to a recent version of the novel, published by Canongate, with words which testified to how much it had influenced her.

She said: “Sunset Song is, without a shadow of doubt, my favourite book of all time. That I would have said that without hesitation when I read it for the first time back in my teenage years is not surprising.

Sunset Song ‘had a profound impact on me’

“But that I say it still, more than thirty years and hundreds of great books later, demands more examination.

“My conclusion is that the love I feel for Sunset Song is not just an appreciation of its considerable literary quality; it is as much, maybe more so, a reflection of the profound impact it had on me at a formative time of my life.

“In no small way, I owe my love of literature to Sunset Song.”

Ms Sturgeon continued: “It is said that Lewis Grassic Gibbon (just 33 when he died, even younger than that other Scottish genius Robert Burns at the time of his death) wrote this masterpiece in six weeks.

“In doing so, he gifted us one of the finest literary accomplishments Scotland has ever known.”

One can agree or disagree with these sentiments.

One can make a case for other Scottish books, by Robert Louis Stevenson, Sir Walter Scott, Muriel Spark, the collected poems of Robert Burns or more recent authors.

But, in the end, nobody who has ever read Sunset Song will not shed tears and be reminded of the one thing all of us share: mortality.