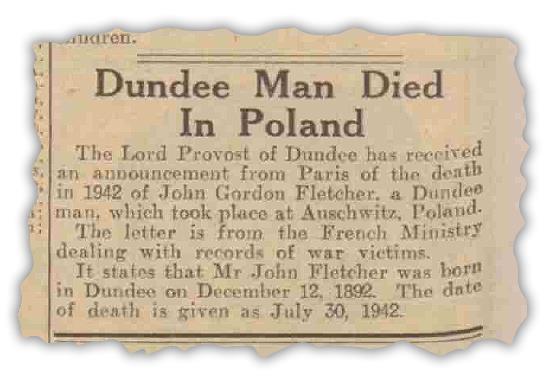

It was a headline tucked away inside the Evening Telegraph of November 23 1946 that might easily have been overlooked.

‘Dundee man died in Poland’.

The three paragraphs on page four confirmed the death of John Gordon Fletcher following correspondence from the French Ministry.

But it was the year and the place where he died which was most significant.

“The Lord Provost of Dundee has received an announcement from Paris of the death in 1942 of John Gordon Fletcher, a Dundee man, which took place at Auschwitz, Poland.

“The letter is from the French Ministry dealing with records of war victims.

“It states that Mr John Fletcher was born in Dundee on December 12, 1892. The date of death is given as July 30, 1942.”

Who was John Fletcher?

Fletcher remains the only known Dundonian to have died in the Nazi death camp, where at least 1.1 million people were murdered between 1940 and 1945.

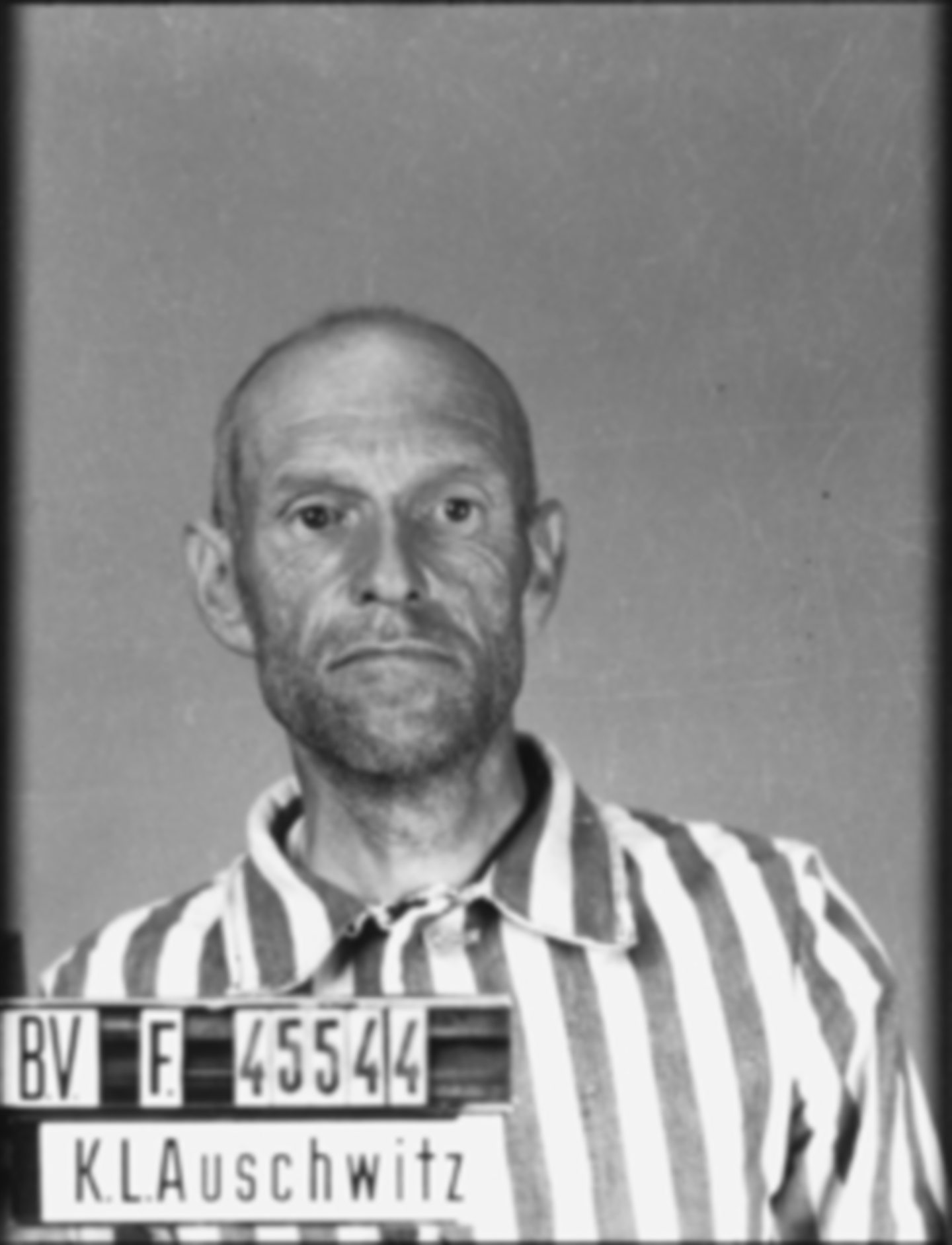

He was a hero but to his Nazi aggressors he was simply number 45544.

Fletcher’s story of courage wasn’t public knowledge for decades.

Fletcher was born in the Overgate on December 12 1892.

He was the son of Margaret Robertson and John Gordon Fletcher, who was a sea captain.

He moved to France in 1913.

Fletcher served with the Intelligence Corps during the First World War.

He received the 1914-15 Star and the French military medal for his distinguished service as a British soldier by the French government.

According to his military registration card, Fletcher was 1.64m tall with “brown hair and grey-brown eyes, a broad forehead and a fairly strong nose”.

In 1919 he married Lucia Fontaine, who ran a bistro in the town of Albert in the Somme region, before becoming a French citizen in 1921.

By this time, he was using the French version, Jean.

Fletcher was arrested by German police

He worked at the government-owned Potez aircraft factory on the outskirts of Albert, which was the largest aircraft factory in the world.

When the Germans swept through France in 1940 they requisitioned the factory because they needed aircraft parts.

Fletcher continued to work at the plant but he was arrested by German military police on May 20 1942 after being betrayed by an informant to the Gestapo.

A father and son working at the factory, Ernest and Rene Pignet, were arrested at the same time and the three men were locked up at the Albert City Hotel for two days.

The Pignets were secretly helping shot-down Allied airmen and prisoners of war to evade capture as part of an underground escape line.

The French authorities – who operated under direct Nazi control – asked why Fletcher had been arrested as he was “neither Jew nor Freemason nor political”.

They wrote to his wife Lucia saying they didn’t know why he had been taken but it was suggested that he assisted the Pignets “in the same affair”.

Fletcher could speak both French and English, which would have been an enormous assistance to British servicemen.

The three men were moved to Frontstalag 122 in Compiegne, which was a German military prison used as an internment camp primarily for political prisoners.

Fletcher was registered under the number 5821.

In June 1942 he was selected with more than 1,000 hostages who were going to be deported in retaliation for the activities of the Resistance despite never being tried by a court.

Cattle wagons took Fletcher to Auschwitz

At dawn on July 6 1942 the prisoners were forced at gunpoint into cattle wagons at Compiegne station to go to Poland.

The journey took two and a half days without water, food or sanitation.

The deportees did not know where they were going and when they arrived in Auschwitz they were not allowed to write to their families.

Fletcher was given the number 45544 on arrival at the Auschwitz base camp.

He was photographed before the prisoners were all marched on foot to Birkenau.

Fletcher was wrongly classified as a ‘French Jew’ on registration and received a ragged uniform and a pair of shoes and was sent to work at the camp.

Archivists from the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum said Fletcher would have been assigned the prisoner category “simply by human error”.

No Jew was intended to survive Auschwitz.

Fletcher lasted just 21 days.

The death certificate that was drawn up by the SS administration indicated “weakness of the heart muscle” as the cause of his death.

These were usually fictitious.

Poles and other non-Jews at Auschwitz were mostly starved, poisoned or lined up against the infamous Death Wall and shot.

The Jews were herded into the gas chambers.

The bodies of the disappeared – whatever the circumstances of their death – were reduced to ashes in the crematoria or in open-air incineration pits.

Fletcher’s documents saved by Resistance

In November 1944, as the Nazis prepared to abandon Auschwitz, they began dismantling and dynamiting three of the crematoria at Birkenau.

The fourth had been destroyed in October, during a short-lived inmate revolt.

The Nazis destroyed most of the camp records to cover up their crimes but Fletcher’s documentation escaped the systematic destruction by the SS of their archives.

Fletcher’s registration photo was among 522, which the death camp’s interior Resistance had camouflaged to save them from destruction.

The French discovered his details in the remaining files including the picture of him in the now-infamous striped uniform that was given to inmates.

In October 1945, following a petition by wife Lucia, Fletcher’s death certificate was amended to include the words: ‘Mort pour la France’ – ‘Died for France’.

On November 16 1946 the registrar on duty at the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War (ACVG) drew up Fletcher’s official death certificate.

The date of death was fixed at July 30 1942.

He was 49 when he died.

More like this:

‘There were no words’: Sandy Michie was the first British doctor to enter Belsen concentration camp

Blairgowrie man Jack Stitt was a Gordon Highlander who refused to let the Death Railway defeat him

John Morrison: The Moray hero whose body was lost for 100 years

Conversation