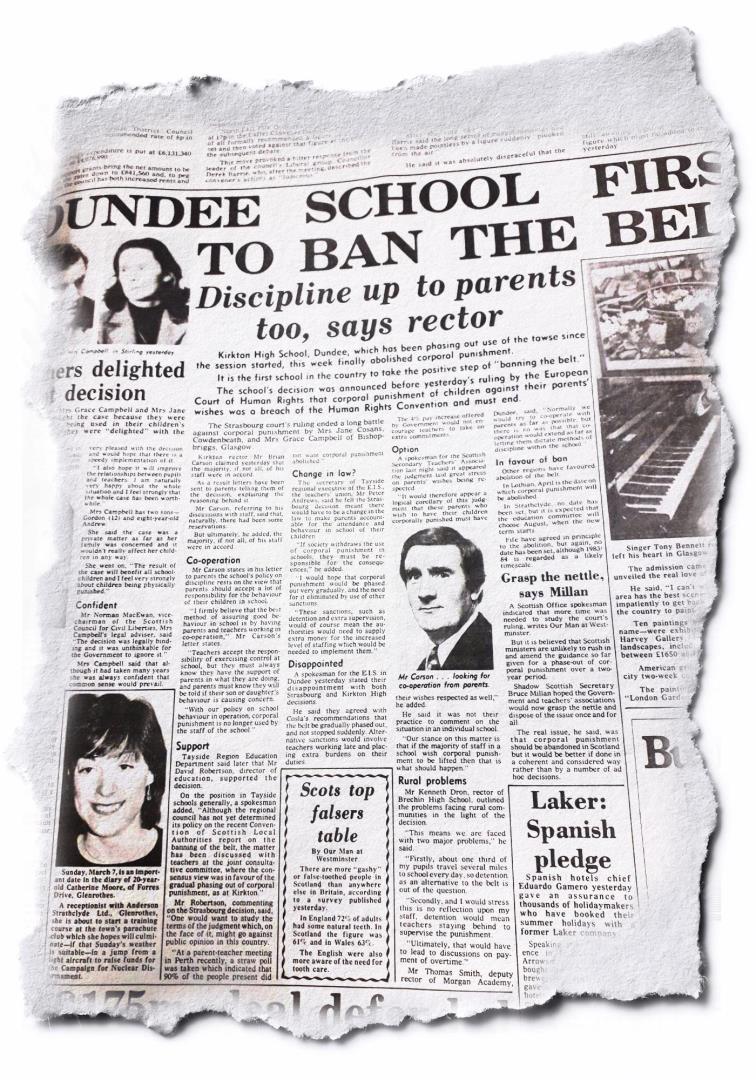

Kirkton High in Dundee became the first school in Scotland to consign the belt to history in February 1982.

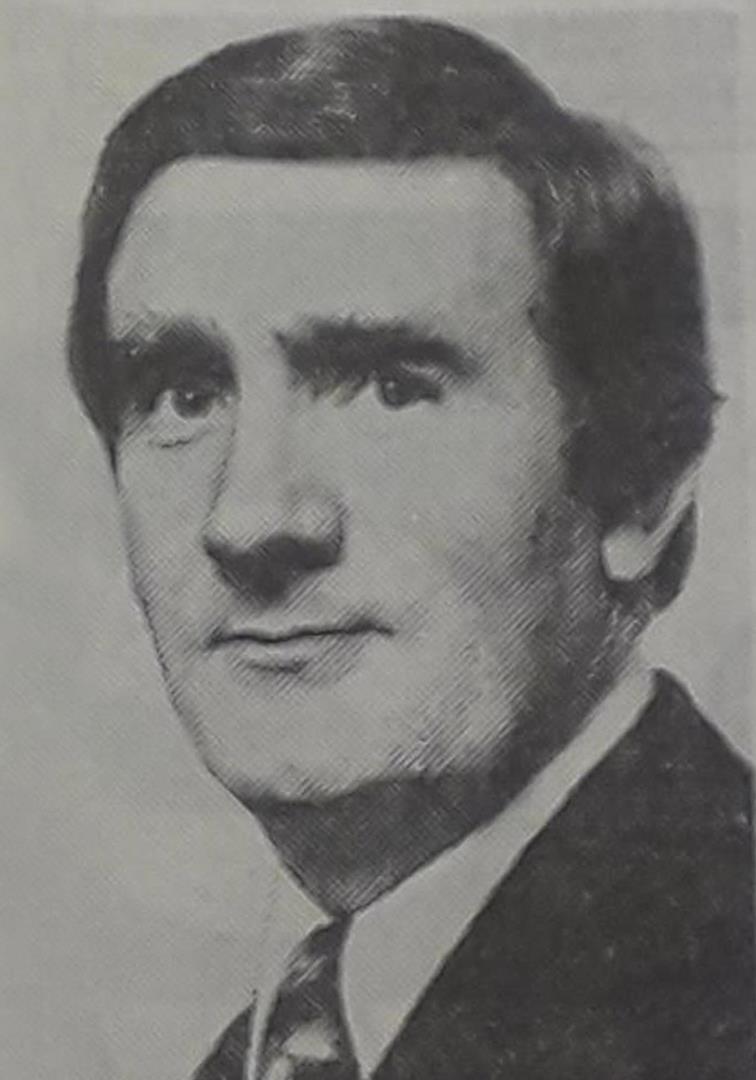

Kirkton High rector Brian Carson said the majority of his staff was in agreement with the decision to stop dishing out beatings to children.

Mr Carson said its discipline policy now rested on the view that parents should accept responsibility for the behaviour of their children in school.

Corporal punishment had been common against unruly pupils since ancient times but public opinion was slowly starting to change by the end of the 1970s.

The weapon of choice at the time was the tawse.

Here was a heavy leather strap made in Lochgelly that was split into two or three tails, to be used by teachers to give out six of the best.

Mr Carson said: “I firmly believe that the best method of assuring good behaviour in school is by having parents and teachers working in co-operation.

“Teachers accept the responsibility of exercising control at school, but they must always know they have the support of parents in what they are doing, and parents must know they will be told if their son or daughter’s behaviour is causing concern.

“With our policy on school behaviour in operation, corporal punishment is no longer used by the staff of the school.”

Kirkton decided to ban the belt just 24 hours before a landmark ruling was made by the European Court of Human Rights following a three-year battle by two mums.

Grace Campbell took her case to Strasbourg in 1979 when Strathclyde regional education authority refused to guarantee her 11-year-old son would not be hit.

Jane Cosans brought a similar case against Fife Council’s education authority after her 15-year-old son, Jeffrey, refused to be belted at Beath High in Cowdenbeath.

The court ruled that beating school children against their parents’ wishes was a violation of the European Convention on Human Rights.

But the move didn’t go down well with all teachers.

Overtime concerns

Kenneth Dron, rector of Brechin High, outlined the problems facing rural communities in light of the decision taken in Strasbourg.

He said: “Firstly, about one third of my pupils travel several miles to school each day, so detention as an alternative to the belt is simply out of the question.

“Secondly, and I would stress this is no reflection upon my staff, detention would mean teachers staying behind to supervise the punishment.

“Ultimately that would have to lead to discussions on the payment of overtime.”

Thomas Smith, deputy rector of Morgan Academy, said: “Normally we would try to cooperate with parents as far as possible, but there is no way that cooperation would extend as far as letting them dictate discipline within the school.”

Tayside was already aiming to gradually phase out the use of the belt after a working party from the local authority body Cosla published a report on its abolition.

Education director David Robertson said he supported Kirkton High’s decision.

“Although the regional council has not yet determined its policy on the banning of the belt, the matter has been discussed with teachers at the joint consultative committee, where the consensus view was in favour of the gradual phasing out of corporal punishment, as at Kirkton,” he said.

“One would want to study the terms of the judgement, which, on the face of it, might go against public opinion in this country.

“At a parent-teacher meeting in Perth recently, a straw poll was taken which indicated 90% of the people present did not want corporate punishment abolished.”

Fife banned the belt by the start of the 1983 school term.

Corporal punishment was abolished in Tayside’s 191 primaries in April 1984 and restricted in secondary schools to pupils whose parents permitted it.

By that stage 11 of the 32 secondaries had already banned the belt, before corporal punishment was finally abolished in all state schools in 1987.

Alternatives now included detention and exclusion from school but did the behaviour of pupils improve following the removal of the belt?

Exclusions rose from 165 in 1983/84 to 382 in 1984/85 and 507 in 1985/86.

A working party set up to monitor behaviour in Tayside schools following the belt ban found what was described as a “worrying deterioration in standards of discipline”.

“Changing standards in contemporary society, reflected in increased levels of marital breakdown and family de-stabilisation, have brought in their wake many problems for schools.

“More immediately, the withdrawal/restriction of corporal punishment is seen by many as a major factor in this decline.

“A substantial majority of rectors reported a marked deterioration in the general level of school discipline, and most attributed this deterioration to the withdrawal of the belt from the classroom.

“Almost all complained about the cumbersome, time-consuming and relatively less effective nature of the alternatives to corporal punishment.”

Since the ending of corporal punishment, education authorities have had to resort to non-violent means to prevent and curb disorder in schools.

A survey conducted in 2011 suggested almost half of parents believed caning should be brought back to the classroom.

More than nine in 10 parents (93%) and two thirds of children (68%) thought teachers needed to have more authority in the classroom.

More like this:

Death of a Dundee school: Should Linlathen High have been closed in 1996?

Trip back in time: Photographic memories of Kirkton

School days: Memories of Dundee schools throughout the decades