The brother of Fife doctor Harry Goodsir returned home to Edinburgh in 1882 after 29 years in Australia.

Robert Anstruther Goodsir got off the steamer into a Scottish winter and greeted the freezing cold temperatures with “profound astonishment”.

Robert was one of seven children born to medical practitioner John Goodsir in Anstruther and three of his brothers also became doctors.

He studied medicine at Edinburgh University before making two voyages to the Arctic in search of his brother Harry who was lost with the Franklin expedition.

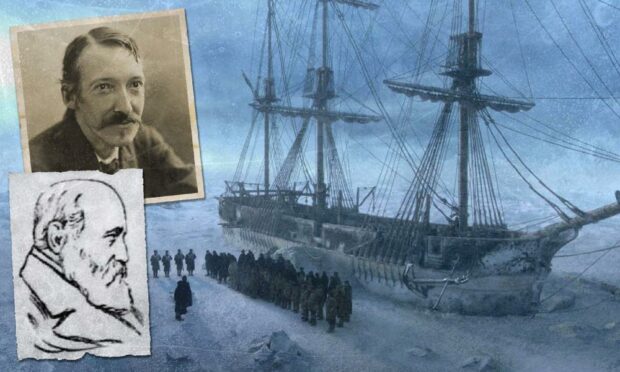

Sir John Franklin departed Britain in 1845 in command of the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror to seek the Northwest Passage.

Then they vanished without a trace.

Robert made the discovery of three graves at Beechey Island.

This gave the first clue to the fate of the crew of the Franklin expedition which fascinated Victorians and ultimately inspired the acclaimed Ridley Scott TV series The Terror which gripped viewers in the UK and America.

Much had changed since Robert left Scotland for Australia in 1853 and his remaining years were a real-life drama worthy of its own Hollywood script.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s eerie classic tale The Body Snatcher incurred Robert’s wrath and his angry criticism of the short story became the stuff of legend!

Burke and Hare

Michael Tracy, of Chicago, Illinois, one of Robert’s closest living relations, has spent over a decade researching the distant medical branch of the family.

“The Pall Mall Gazette, in a Christmas Extra first advertised the work of Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Body Snatcher on December 9 1884,” he said.

“The short story’s characters were based on criminals in the employment of Dr Robert Knox around the time of the notorious Burke and Hare Murders.”

Edinburgh had several pioneering anatomy teachers in the 19th century including Dr Robert Knox who started his lectures in 1825 with John Barclay.

John Goodsir was absorbed during his first session on descriptive anatomy which was delivered by Dr Knox in the Old Surgeons Hall.

Indeed John’s interest became so fixated by practical anatomy that he wrote to his father asking for his permission to become a surgeon.

The path forged by John Goodsir was closely followed by his brother, Harry, with whom he had shared a thirst for scientific knowledge from an early age.

Mr Tracy said: “The teaching of anatomy was predicated on a sufficient supply of cadavers usually supplied by those convicted of capital crimes.

“But with the rise in prestige and popularity of medical training in 19th century Edinburgh, this legal supply of corpses failed to keep pace with the demand, and, as a direct consequence, students, lecturers, and grave robbers – also known as resurrection men – began an illicit trade in exhumed cadavers.

“It was against this backdrop that Dr Knox rose to professional prominence only to be disgraced by posterity as the beneficiary of body-snatching.”

His classrooms increased with more students to the point that Dr Knox was lecturing three times a day so great was the demand for his expert tuition.

Dr Knox stayed silent when the Burke and Hare scandal broke.

He never acknowledged any meaningful connection with Burke and Hare and was never prosecuted which outraged much of Edinburgh society.

Mr Tracy said: “Although a fictionalised account of long past activities, Stevenson’s sensational reconstruction highlighting a notorious failure of medical ethics outraged the Edinburgh medical profession including a member of the Goodsir family.

“Housed in the National Library of Scotland is an undated and unsigned letter rebutting Stevenson’s anonymised criticism of Dr Knox.

“This letter was never published but has been attributed to Robert Goodsir who was by then the only surviving doctor of the Goodsir family.”

In this letter to the Pall Mall Gazette Robert claimed that the accusation against Dr Knox never amounted to more than a “vulgar fama clamosa” – a noisy rumour.

He wrote: “It will be said of course, that The Body Snatcher is only a piece of fiction.

“A pleasant piece of fiction, certainly, to attach the stigma of cold-blooded deliberate murder to the name and memory of a man who has relatives and friends and admirers still amongst the few still living of his many thousands of pupils.

“When in the guise of fiction an author maligns in the most unmistakable terms the memories of men who have not long departed, he should recollect that some one still may live who can answer and refute his calumnies.”

Mr Tracy said the respect and admiration in which Dr Knox was held was evident from the reciprocated friendship of John and Harry Goodsir.

He concluded: “It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that upon the publication of Stevenson’s work, it was their brother Dr Robert Goodsir who sought to protect Knox’s reputation despite the popularity of a novel, now transposed to the medium of horror movies as one of that genre’s most literary offerings.”

Edinburgh Castle

Robert continued his writings, took an active interest in the genealogy of his family’s illustrious past and became a member of the Ex Libris Society.

He contributed as an exhibitor of his family’s portraits and medical engravings at the Scottish National Portraits Gallery and researched and drew 107 heraldic drawings containing 207 blazons for the Edinburgh-based architect, Hippolyte Jean Blanc.

Things didn’t quite go to plan which prompted another ugly spat!

Blanc requested Robert to prepare and supply the drawings at the latter end of 1888 because he was “well known for his knowledge of heraldry”.

Blanc handed over the drawings to master craftsman Alexander Ballantine so that he might prepare the stained glass windows in the Great Hall of Edinburgh Castle.

Mr Tracy said: “Robert had several meetings with Ballantine and indicated he expected Blanc to pay him 150 guineas for his research into, and preparation of, the drawings, but Blanc would only offer him 20 guineas.

“As a result, Goodsir took Blanc to the Court of Session on July 9 1890.

“However, it is unknown whether or not the Inner House of the Court of Session gave a decision – perhaps the case was settled out of court.

“It is also unclear as to whether Blanc indeed used Robert’s drawings for the actual stained glass windows in the Great Hall of Edinburgh Castle.”

As the last of his immediate family, Robert used his remaining years to their fullest including the generous donation of hundreds of books and a bust of his late brother, the esteemed Professor of Anatomy, John Goodsir, to Edinburgh University.

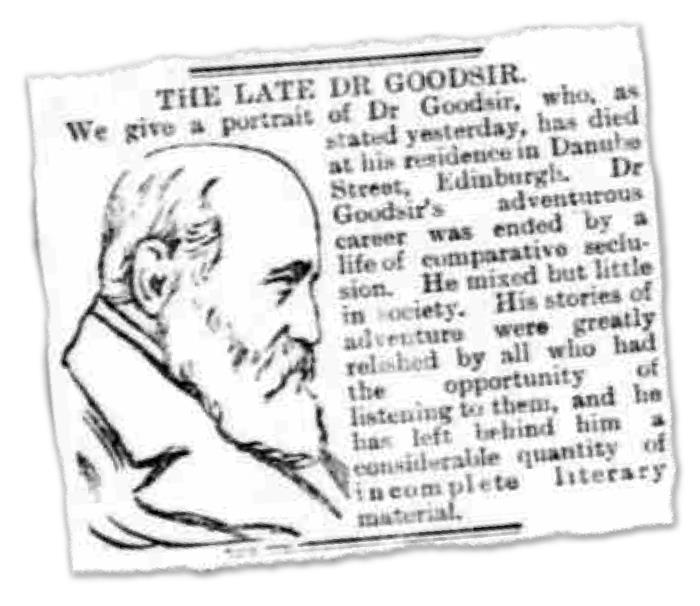

Robert died aged 71 on January 17 1895 following a short illness and was buried at Dean Cemetery in Edinburgh but what is his legacy today?

Mr Tracy said: “Robert Goodsir lived a life of varied experience and adventure such as is given to few men.

“By the time he was 28 he had already been to the Arctic regions – twice.

“His early youthful dream of travelling to Australia and New Zealand had been accomplished.

“Truly, he was a lion of the season.

“And yet upon his return to Edinburgh, and now in his twilight years, he acquired great knowledge of antiquarian topics, genealogy, and heraldry which were perhaps his favourite studies.

“His talents in these areas are still evident today as illustrated by his carefully researched ancestral pedigree of his own family.

“His legacy to posterity can be found in the University of Edinburgh Special Collections where his own and his siblings’ extensive library of books can still be viewed today.”

More like this:

More like this:

The Terror 2? Dundee actor to reprise role on Franklin’s doomed ship

The Terror: Could hair strands from Fife doctor Harry Goodsir solve skeleton riddle?

Die Hard: Is iconic action hero John McClane really from Scotland?