In October 1929 Mr William Johnston was digging a pit in the garden at the rear of his home when his spade struck what appeared to be a stone.

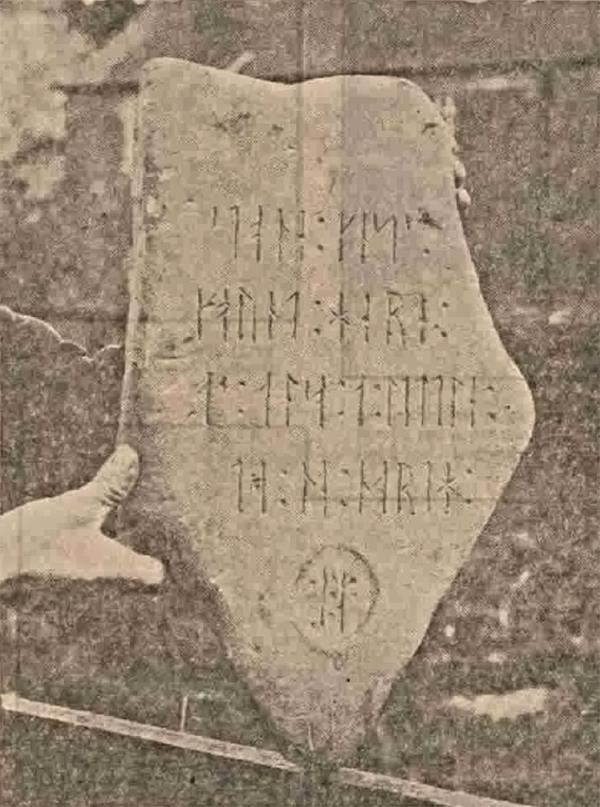

Mr Johnston unearthed the stone, which proved to be flat slab about 18 inches long and 13 inches across, bearing unusual lettering on one side.

Mr Johnston was a mason living in the village of Charleston, near Glamis.

He discovered the rune when digging a hole at the bottom of his garden and suspected that its markings were a form of ancient writing.

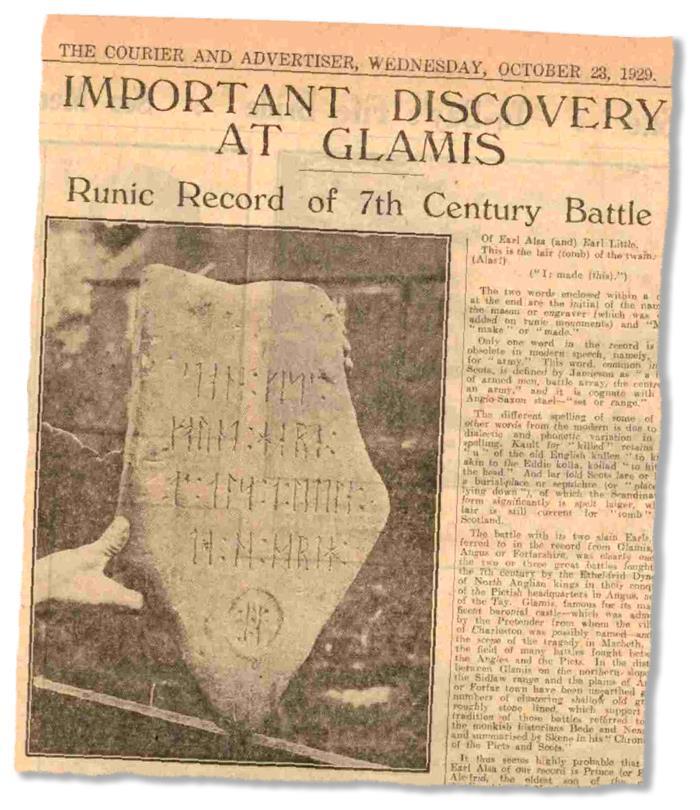

He wrote to The Courier after making the discovery and the newspaper asked Lieutenant-Colonel L. A. Waddell to study the artefact.

Lt Col Waddell was a well-known authority at the time on archaeological subjects and had written several novels on British history.

The result of his study said that the stone was a record of a battle that had happened in the area in the 7th Century.

Lt Col Waddell was confident that the inscriptions on the stone were old Gothic runes.

He then translated the runes and offered a modern English translation, which read: “The Army stone coffins of the Killed here; Runic Record of 7th Century Battle Of Earl Alsa and Earl Little. This is the (tomb) of the twain.”

The battle with its two slain Earls, referred to in the record from Glamis, was one of the two or three battles in the 7th Century where North Anglian kings conquered the Pictish headquarters in Angus.

The Earl of Strathmore, who owned the estate that Mr Johnston’s home was on, told The Courier he was “delighted” someone had been able to translate the find.

However, a few weeks after Mr Johnston’s discovery, other archaeologists took a look at the suspected Pictish stone.

They disagreed with Lieutenant-Colonel Waddell’s findings and instead believed the stone had been planted recently, in the 1920s, with engravings added by a fellow archaeologist as a practical joke.

Dr Mackenzie of the Ancient Monuments Commission offered that the runes were of Scandinavian origin, and not Anglican like the Lieutenant-Colonel said.

His Scandinavian translation read: “Stone cist. Found here. And also to the North.”

This revealed it was a modern English inscription written in runic characters, and why Dr Mackenzie was confident his translation proved the stone was a hoax.

Other local worthies such as Mr Douglas Hunter wrote to The Courier and informed them of other mistakes in the Lieutenant-Colonel’s translation.

He noted that one of the symbols was not used until after the 15th Century – too late to be from the suspected time period.

Then, about a month after discovery, the stone faded into obscurity.

Over the years, many attempts have been made to decipher the stone and confirm its origins.

Some believe its discovery was simply a prank.

So where did this unusual discovery really come from?

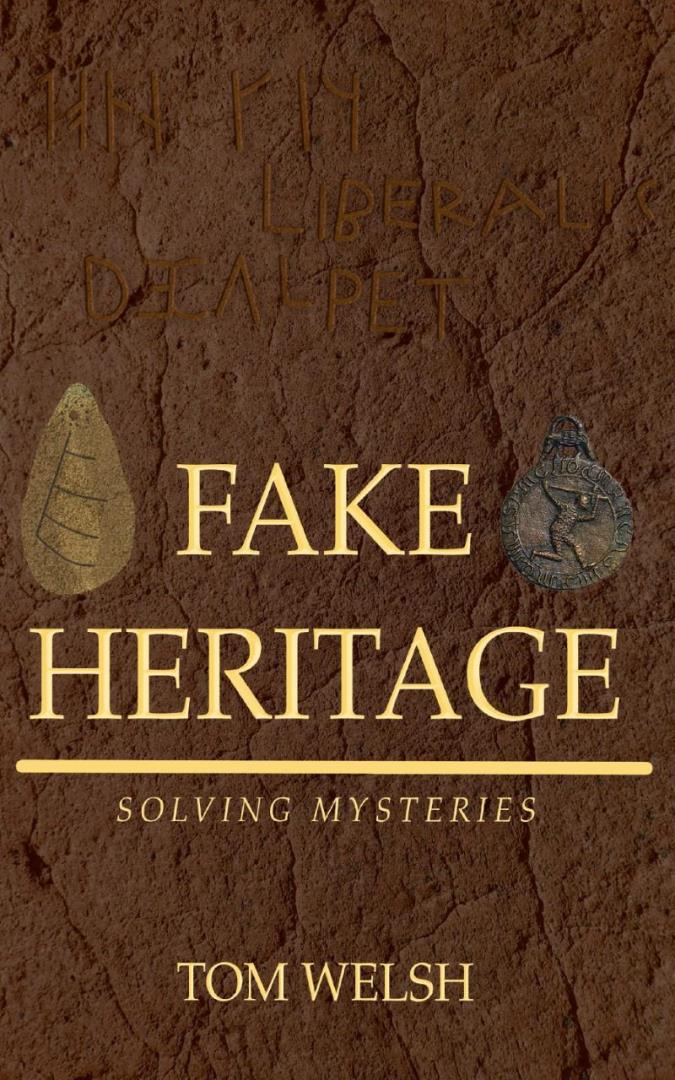

The Glamis stone mystery has also captured the imagination of author Tom Welsh.

The story is featured in his book, Fake Heritage: Solving Mysteries.

The book looks at a number of archaeological mysteries, arising from fakes, hoaxes and misrepresentations, from the 1830s to the 1930s.

Mr Welsh said: “Undoubtedly the stone wasn’t what it seemed at first.

“Clearly it was not ancient, but calling such phenomena a hoax is not always scientific.

“The circumstances are not that straightforward. For example, the way it was found, unless that itself was a fiction, is not so easily explained.”

Mr Welsh added that there were candidates who could be the target of such a hoax.

He explained: “One candidate is the newspaper that carried the original discovery, set up by a rival.

“The other candidate is the eccentric antiquary who was asked to examine it.

“However, as hoaxes go it is a very long shot. It may simply provide a good demonstration of the need to scrutinise the evidence rather than jump to conclusions.”

The Glamis stone is one of three Scottish mysteries in the book.

Mr Welsh’s book draws a comparison between the Glamis hoax and the Glozel controversy a few years earlier.

Objects had been found during an excavation in 1924 at Glozel, near Vichy, in France.

Archaeologists found an underground chamber that, when excavated, produced hundreds of artefacts, including inscribed clay tablets.

By 1927 it had become an international controversy, and many believed it to be a hoax.

It later proved mostly genuine, with some of the artefacts being early medieval rather than prehistoric.

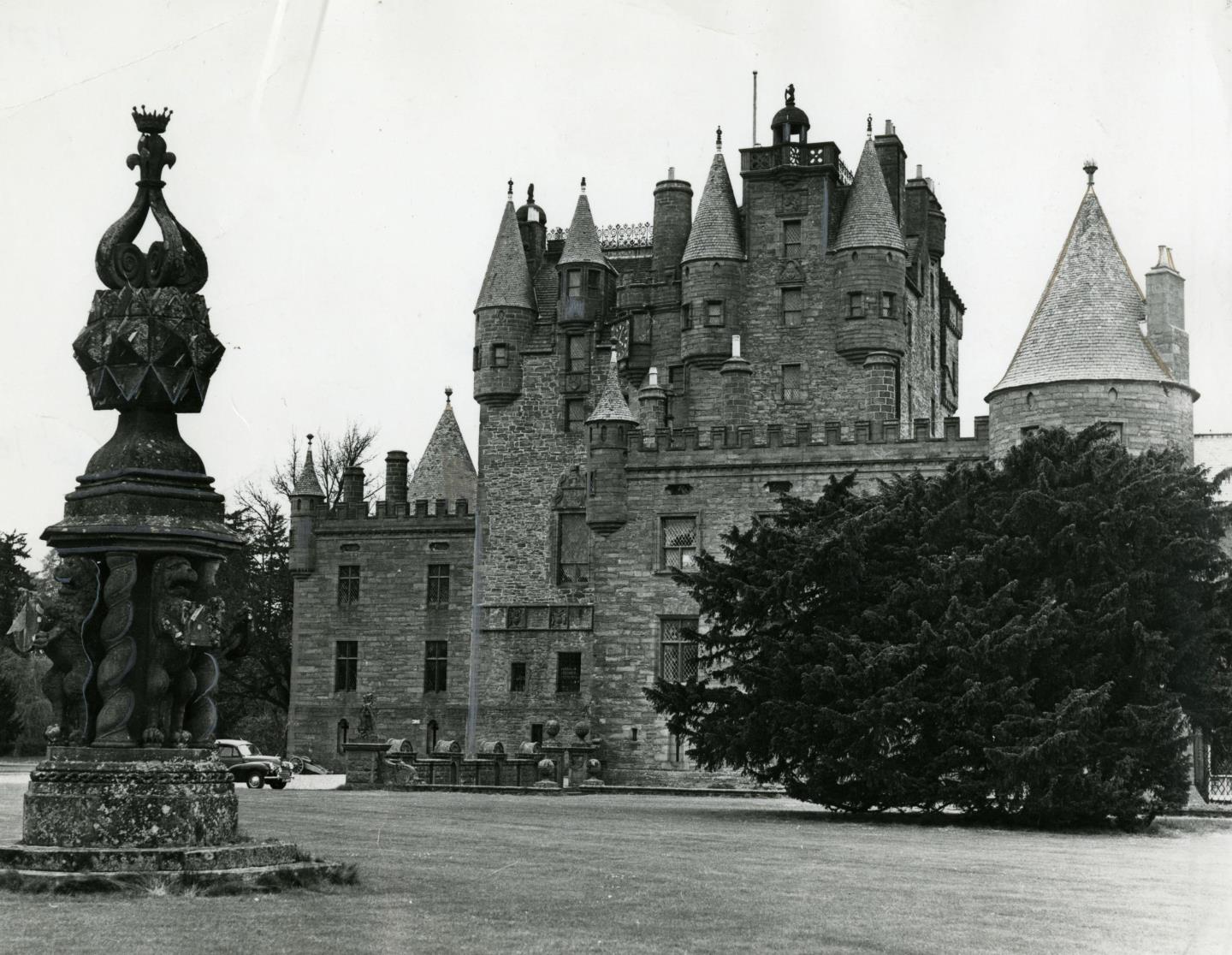

Glamis – famous for its castle, which is featured in Shakespeare’s Macbeth – was the scene of many battles fought between the Angles and the Picts.

It was the childhood home of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, wife of George VI.

Nearby villages have prehistoric traces. An intricately carved Pictish stone known as the Eassie Stone was found in a creek-bed at the nearby village of Eassie.

The Eassie Stone is now located in the ruined Eassie Old Parish Church in Angus.

- Mr Welsh’s book, Fake Heritage: Solving Mysteries, is available on Kindle for £2.99.