It was one of the darkest episodes of the Second World War – and hundreds of north-east Scots were among those who suffered the worst privations in the aftermath of the fall of Singapore.

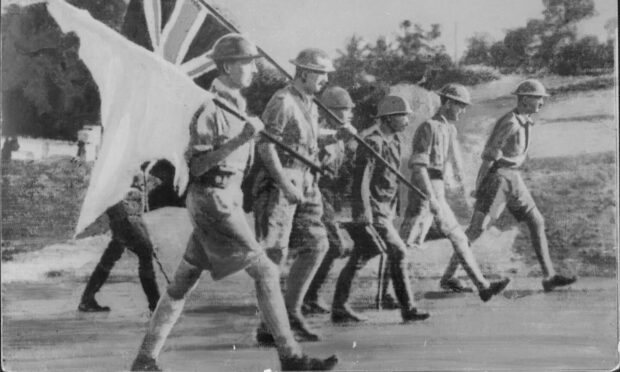

The collapse happened on February 15 1942, when more than 130,000 Allied troops, from Britain, Australia and India, were captured by Japanese forces.

Winston Churchill was appalled when he heard the news and subsequently described the loss of Singapore as “the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British military history”.

The many Scottish soldiers with the 2nd Battalion Gordon Highlanders were not committed to the battle until it was too late and 40% of their number subsequently died in prison camps: victims of often inhumane treatment at the hands of captors who did not observe the Geneva convention.

The Gordon Highlanders had spent the previous four years in Singapore carrying out vital work, including safeguarding routes to Australia, New Zealand and the rest of the Pacific rim.

They were a redoubtable group, and more than 600 of their number came from within a 50-mile radius of Aberdeen.

But hundreds of these young men suffered excruciating deaths thousands of miles away from home.

Their families had no idea for months and even years afterwards whether they were dead or alive.

And that prompted Mrs Irene Lees, the wife of Major R G Lees, the second-in-command of the Gordon Highlanders, to establish a support group for the many anxious relatives who desperately sought any scrap of information on their loved ones.

They held regular meetings and shared the meagre amount of news coming back from places such as Singapore and Thailand and raised funds to send parcels to the regiment’s prisoners of war, both in the Far East and Germany.

But sadly, although these “goodies” did reach their intended recipients in Europe, the Japanese never distributed any of the goods to their prisoners.

Mrs Lees had lived in Singapore with her husband and was only evacuated on February 12, just 72 hours before the island fell.

She subsequently did her utmost to help anybody with a connection to the Gordon Highlanders, but, in too many cases, was forced to chronicle tragic stories of fallen comrades.

The war in the Pacific had started when the Japanese bombed Singapore on December 8 1941, around the same time as they were attacking Pearl Harbor.

The latter assault took place on December 7 in Hawaii, but it is on the other side of the International Date Line, so it is often misunderstood that these events were virtually simultaneous.

The Japanese then invaded northern Malaya and advanced rapidly down the Malay Peninsula and, by the end of January, Singapore was under threat.

This was an almost unimaginable scenario, considering it had been regarded as an impregnable fortress guarding the vital routes to Australia, New Zealand and the wider Pacific.

But though the Gordons were elite, highly trained soldiers and well acclimatised, they were summoned into the fray too late to halt the rapid momentum that had been built up by their adversaries.

Their role was to defend the artillery positions and the 2nd Battalion was held back from the battle of Malaya until it was almost over: a calamitous misjudgement in many people’s eyes.

They were finally committed to the battle on January 26, just three weeks before the surrender and fought gallantly.

George Clyne died of multiple gunshot wounds when he charged a machine gun post without any thought for his own safety.

The Gordons’ Medical Officer, Captain Frank Pantridge, was awarded a Military Cross for continuing to treat wounded men while subject to continuous bombing and shelling.

Major Walter Duke and Captain Ludovic Farquhar were awarded the same decoration for leadership and bravery in the battle, disregarding their own safety and inspiring their men.

Bandsman Corporal Mark Allen was a stretcher bearer and acted with great heroism as chaos reigned around him.

He organised and led carrying parties for ammunition which he successfully delivered to troops at a critical time.

In addition, he brought back several casualties when machine gun fire and shelling was continuous in the area.

He was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal, which is second only to the Victoria Cross as a gallantry award to an enlisted man.

And yet, while there was conspicuous courage from so many of the troops, they had been left in an impossible position and thousands of them had to endure grim conditions in PoW camps where many perished from disease, malnutrition or mistreatment by their captives.

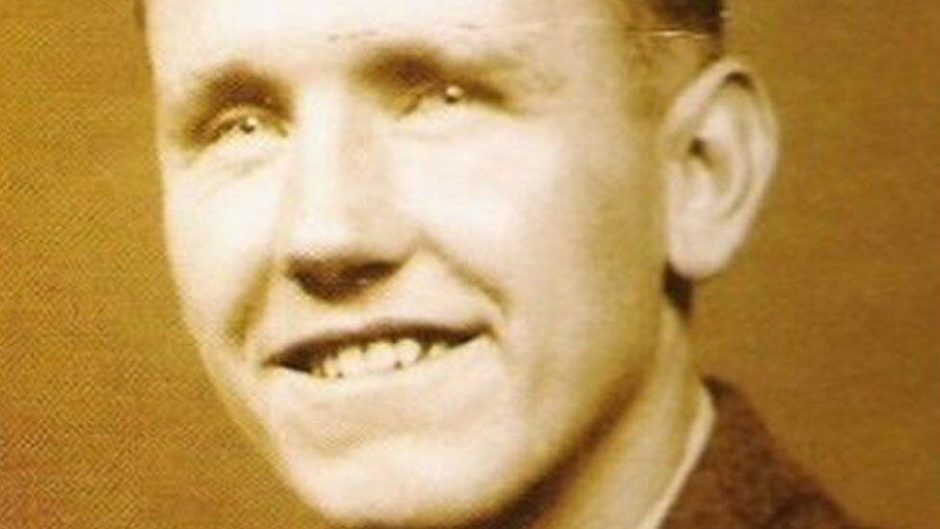

There were notable exceptions, such as the case of Alistair Urquhart, from Newtonhill, who somehow survived myriad misfortunes between his incarceration and the end of the global conflict in 1945.

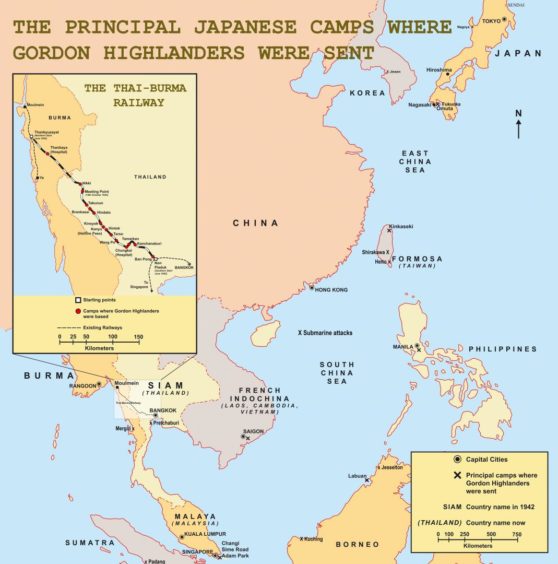

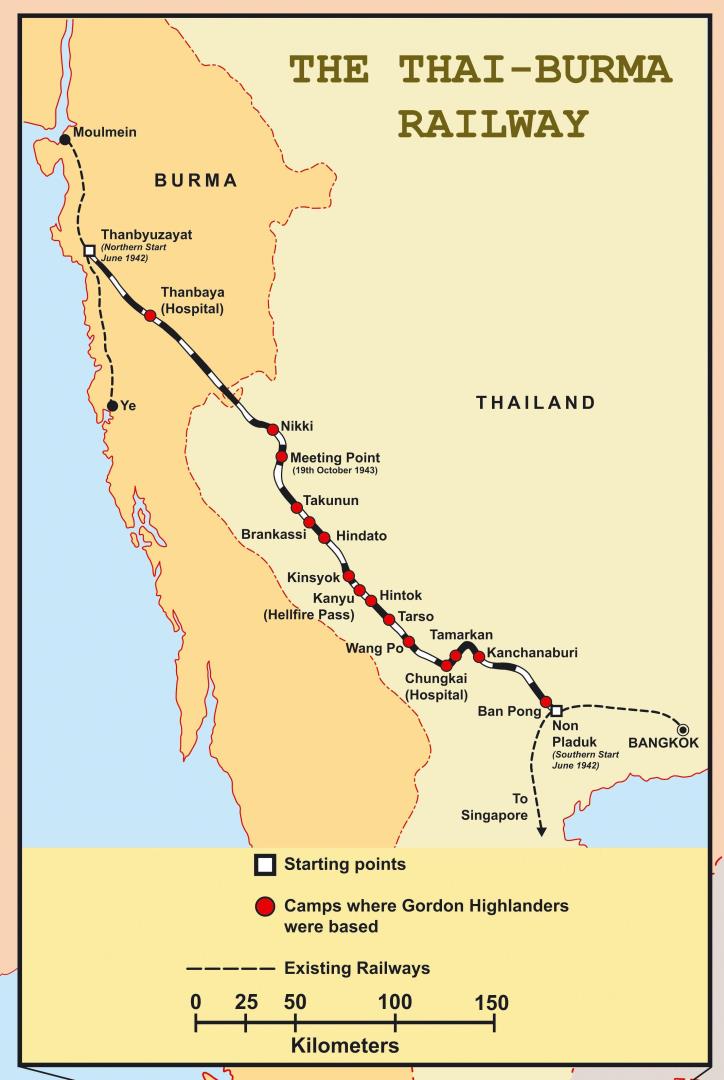

Mr Urquhart, who recorded his remarkable story in the book The Forgotten Highlander, was forced to work as a slave labourer on the notorious Thai-Burma Railway; was later shipwrecked in the South China Sea when his “hellship” was torpedoed; and he was one of a handful of Gordon Highlanders to witness the second atomic bomb cause enormous devastation to Nagasaki.

He died in 2016 in Broughty Ferry at the age of 97 and his heroic resistance in adversity has been celebrated by people such as Stewart Mitchell, a volunteer researcher at the Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen.

Mr Mitchell, who chronicled their experiences in his poignant book Scattered Under the Rising Sun, said: “It’s beyond our comprehension these days to understand what these men went through.

“As you might expect of the Gordon Highlanders, around 60% of the men were from with 50 miles of Aberdeen, and there are many families in the region from almost every community with a connection to these men.

“That’s why it is so important to preserve their memories, so that future generations can understand the realities of war.

To be honest, many of us hardly knew where Singapore even was before we travelled out there… but so many of these lads are over there forever.”

Alistair Urquhart

“We saw three of the last survivors pass away in 2016 – Alistair Urquhart, William Strachan (from Fetterangus), who died in British Columbia, aged 95, and William Bremner (from Turriff), who died in Connecticut, aged 90.

“He enlisted at 15 so he was only 16 when he was captured and sent to the Thai-Burma Railway.

“It must be unlikely that anybody else is still alive after all the years, so these courageous men were the last of their generation.

“We should never forget their sacrifice.”

Mr Urquhart was matter-of-fact in discussing the consequences of the Fall of Singapore.

He always regarded himself as one of the “lucky” ones, who was “blessed” to have been granted the opportunity to return to his homeland and grow old in the company of his family and friends.

But, as he said towards the end of his life: “So many of my pals never came back.

“These were lads who went over there with no idea of how matters would turn out and they had their eyes opened.

“They were young lads from almost every town and village in Moray, Tayside and Aberdeenshire who just wanted to do their duty for their country.

“To be honest, many of us hardly knew where Singapore even was before we travelled out there… but so many of these lads are over there forever.”

Their names may not be widely known but, on the 80th anniversary of the Fall of Singapore, they deserve to be commemorated.

- Scattered Under the Rising Sun is available at www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/Scattered-Under-the-Rising-Sun-Paperback/p/20519