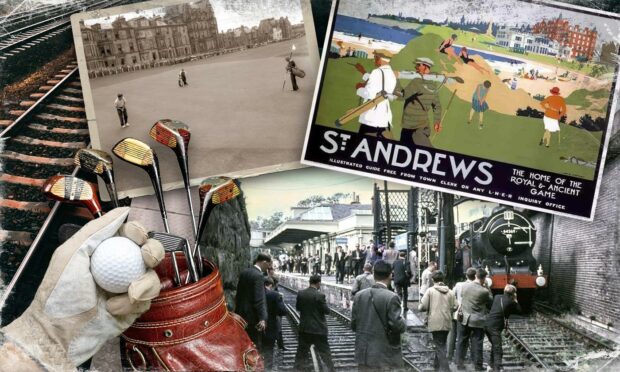

It’s one of the enduring images of Paul Lawrie’s victory in the 1999 Open Championship at Carnoustie; the sight of a packed train stopping briefly to salute the Aberdeen golfer’s triumph.

Yet sadly, there will be no recurrence of these scenes when St Andrews hosts the 150th staging of the world-famous tournament later this year.

There used to be a regular rail service between other communities in Fife and the home of golf, but the Beeching Report meant the route was soon bunkered.

Even now, it seems remarkable that more effort was not made to protect a service which allowed rail passengers to savour so many picturesque sites across a majestic part of the country, especially given the boost to tourism and the economy which the sport now provides to Scotland.

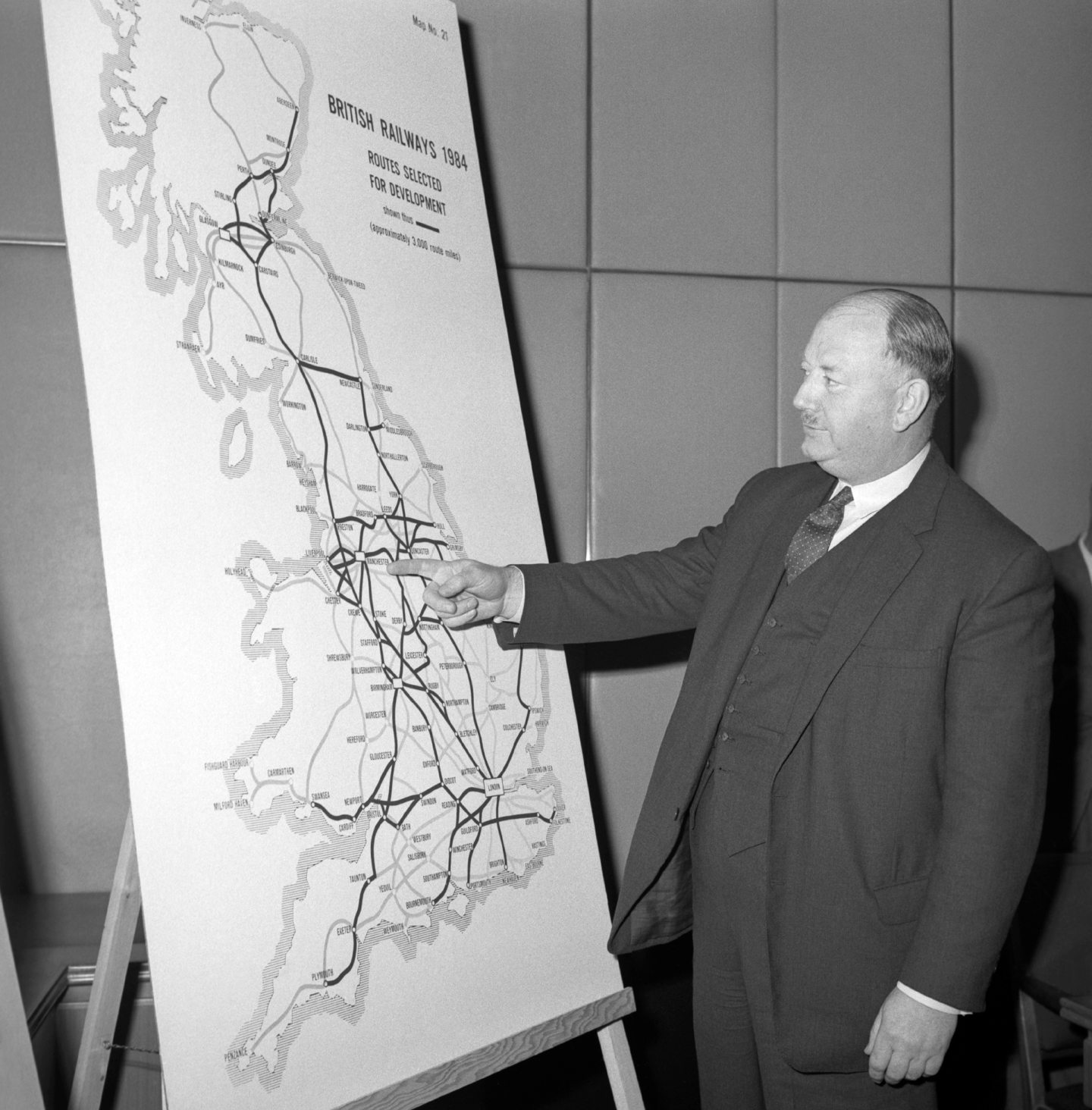

However, none of that mattered when Dr Beeching’s infamous ‘Map 9’ marked the Leven-St Andrews section in black, which denoted that “all passenger services” would be withdrawn during the 1960s.

But was it a necessary decision? Or could more have been done to preserve the train link throughout the Kingdom and onwards as far as Dundee?

Formal closure proposal notices for the end of trains between Thornton Junction and Dundee via Crail – but leaving Leven and St Andrews stations unscathed (for the moment) – were posted in local newspapers, including the Courier on September 2 1963 and immediately sparked protests.

The Five Burghs Committee made it clear in committee rooms and press and letters columns that they would fight the move all the way and insisted that “every possible protest should be lodged by people living between St Andrews and Leven” to halt something which would have a “serious impact”.

And yet, as transport expert David Spaven has recorded in his new book Scotland’s Lost Branch Lines: Where Beeching Got it Wrong, there was a dearth of co-ordinated response to the threatened closures, almost as if many members of the public were unaware what was happening until it was too late.

And, despite the clamour kicked up by various bodies, the initial proposal in the controversial report only received 16 objections from regular travellers, although there was substantial levels of opposition from hoteliers, landlords and landladies, local authorities, teachers and traders.

Nowadays, with social media available to all, campaigns can whip up concerted momentum and attract global backing – but there was none of that in the mid-1960s and all the critics never coalesced into one pressure group.

In which light, it was with a marked lack of a rear-guard action that on September 6 1965 the entire line between Leven and St Andrews closed to passenger trains; and the section from St Andrews to Crail shut completely.

Objectors at a public hearing in Leven on February 17 1964 had argued: “The economy of the East Neuk depended, to a large extent, on summer visitors, mostly composed of families whose practice is to rent accommodation for a fortnightly period” between June and September.

A Courier report on the meeting highlighted some of the significant points made by those present, which included “the financial hardship which would be suffered by a wide range of people, from passengers and commuters to retailers and those who worked in the hotel and catering industry”.

It was a serious business for thousands of people, and passions ran high, but there was still a sense of inevitability about the outcome, given the massive scale of the closures which Beeching’s report had implemented across Britain.

The next stage of the restructuring brought an end to services to St Andrews and the closure of Leven station and, once again, it was ruthlessly efficient.

The local councillors couldn’t really be faulted in their resistance to something which they had instantly recognised would be damaging, considering how little support they received from central government at Westminster, who were scarcely bothered about the fate of stations hundreds of miles away.

And they were given no signs of a reprieve even when a deputation from Fife County Council travelled to London in September 1967 to meet the Minister of Transport and argue the case for the threatened Leven, Newport-on-Tay and St Andrews branches, which were used by scores of people every year.

They could have saved themselves the journey. As Mr Spaven said: “In October, the railway unions were supplied with a memorandum setting out the details of the proposed Leven closure, including the impact on staffing.

“The number of passengers booked at Leven station in the year ended August 1967 totalled 18,659 (with 559 season tickets issued), but the public Heads of Information put this in starker terms.

“During the week ending May 13, the average daily number of passengers alighting from northbound trains at Leven from Monday to Friday was only 81 – [which was] spread across 12 trains.

“The numbers were better during the holiday season, with the average during the week ending July 15 being 145 on Monday to Friday and 491 on Saturday.

“But, overall, these were highly discouraging figures, demonstrating, in the words of [railway expert] John Yellowlees, ‘the long dark shadow cast by the Forth Road Bridge, which had opened in 1964 and, by this time, had also led to the Kirkcaldy-Edinburgh local service frequency being cut.”

In recent years, there has been a revival of interest in rail and the opening of new stations and routes in the Borders, parts of the central belt and the north east and even the re-opening of some of the sites which were scrapped in the Beeching bonfire. Work is continuing to resurrect other routes.

Yet there was an elegiac air about the fashion in which passengers in the 1960s bade farewell to many of the trains which had carried them for years.

The last train from Leuchars to St Andrews ran on Saturday January 4 1969 and was marked by a low-key farewell in Fife, as reported by The Courier.

It said: “As the empty train drew out of St Andrews on its way to the depot in Dundee, passengers joined in singing Auld Lang Syne and sent up three hearty cheers for the railway staff.”

It was only after the services had vanished that those without cars – still a sizeable number of people 50 years ago – were left to depend on buses which, in many cases and, despite promises from the companies, frequently ran late, and proved particularly unreliable during the winter months.

The author doesn’t pretend that trains were a panacea for the region. Neither does he claim that every closure mooted by Beeching was a bad decision.

But he is in agreement with those who concluded: “In the space of barely five years, East Fife had regressed by more than a century back to the era of the horse and trap and at a time when the only railheads had been the newly opened, but distant stations at Kirkcaldy, Cupar and Leuchars.

“The government had spoken and the trains had vanished.”

Mr Spaven has investigated a variety of different decisions which were taken during the 1960s and reached the verdict that the much-maligned Beeching has been unfairly tagged as the bogeyman of the railway bogies.

He stated: “It is not fashionable to say so but, in some ways, Beeching has had an unfair press.

“His promotion of fast inter-city services, ‘merry-go-round’ coal trains from colliery to power station and the pioneering Freightliner (container-carrying) concept took the railway in the right direction, all proving their worth in subsequent decades and continuing to do so today.”

But that didn’t help communities which had previously benefited from rail routes which were simply swept away in less than a decade.

Just imagine if there were still regular trains every day venturing from different parts of Fife to St Andrews to accommodate Open spectators in July.

But you can’t. Instead, the roads will be packed and the traffic jams and bottlenecks will present anything but a fairway to heaven!

- Scotland’s Lost Branch Lines is published by Birlinn at birlinn.co.uk