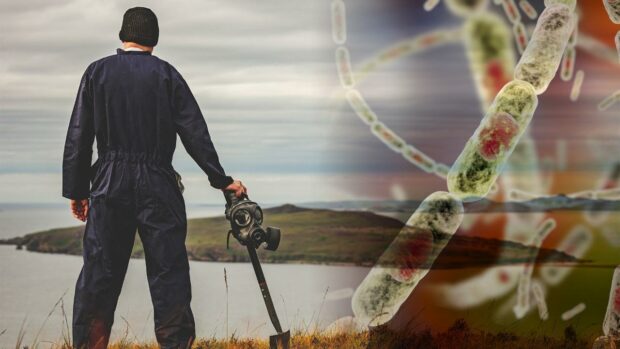

It was the Scottish locale contaminated by deadly anthrax spores and labelled the Island of Death during the Second World War.

Winston Churchill’s attempts to create an “anthrax bomb” were carried out on Gruinard Island, just a few miles off the coast of Wester Ross, which was taken over by government scientists from the MoD’s Porton Down laboratory.

From 1942, people were forbidden to enter the uninhabited isle for fear of the spores they might inhale from the contaminated soil; weaponised bacteria with the potential to remain lethal for decades or even centuries.

Ominous warning signs were erected on Gruinard which declared: “This Island is Government Property Under Experiment”. But scores of animals subsequently died on the mainland in an outbreak before several crofters were hastily compensated and told to remain silent about what had happened.

The previously tranquil site was shrouded in secrecy and, almost 40 years after the controversial scientific experiments, Gruinard was in the headlines again when an environmental group, the Dark Harvest Commandos landed on the island and seized a significant amount of anthrax-infected soil.

To this day, despite the protestors sending packages to Porton Down and Blackpool Tower at the same time as the Conservative Party conference was being staged in the seaside town in 1981, nobody has ever been arrested in connection with their commitment to make the British authorities pay for the effects of what they had done to Gruinard during the war.

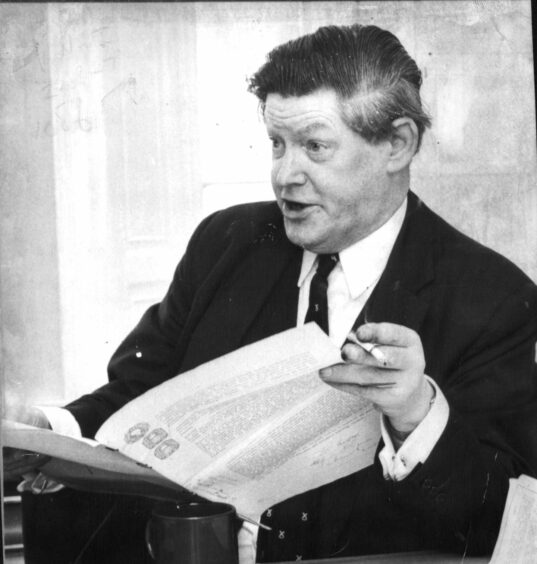

But now, a new documentary has lifted the lid on the story and suggested that the SNP politician and anti-nuclear campaigner, Willie McRae, who was found dead with a bullet wound in his head in the Highlands in 1985 – the cause of his death was never determined – may have had links to the activists.

Mr McRae had previously criticised the poisoning of Gruinard and stated that the Westminster Government should be forced to decontaminate the island.

His condemnation was shared by the teacher and political activist, Kay Matheson, one of four Glasgow University students involved in the removal of the Stone of Scone from Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day in 1950.

The Dark Harvest Commandos did not engage in cheap threats or contemporary sloganising. On the contrary, the letter which they sent to Porton Down was almost Biblical in tone and used such phrases as: “Where better to send our seeds of death than to the place whence they came?”

In 1981, the self-styled commandos revealed details of how they had landed on the island and removed 300lbs of infected soil, as the prelude to leaving a small package of the substance just outside the perimeter fence at Porton Down.

Their aim, they declared, was to force a clean-up of Gruinard.

A letter sent to the media was the catalyst for banner headlines and further outrage was sparked when a second package of soil [later deemed harmless] was found in Blackpool close to the location of the Tory conference.

The group’s measures were described as “irresponsible” by MPs and a special Police Task Force was formed with investigations focused on Wester Ross.

But, despite months of scrutiny, there were no clues and no local residents prepared to speak out about who may or may not have been responsible.

The BBC documentary-makers have spoken to those who recall both the events of 1942 and 1981 and highlighted the anger felt by many people in the community over what was described as “the UK using the Highlands for the development of one of the first weapons of mass destruction.”

One local, Roy McIntyre, recalled the horror of witnessing “little explosions ” as he looked towards Gruinard. Another resident, Danny Grant, said: “I remember, as a child, seeing a big horse being dumped in a hole. Rigor mortis had set in. And there were all these sheep lying in a field….all of them dead.”

The Ministry of Defence was reluctant to acknowledge any of these reports. Even now, some records are sealed up and will remain locked for decades.

The whole place had been poisoned

But, gradually, it was disclosed that 80 sheep had been tethered together and exposed to a small bomb whose detonation had released the virulent spores.

They all died, with post-mortems being carried out, and the scientists seemed satisfied with their work after returning to Porton Down in 1943.

Yet, even in these small Highland communities, there was genuine fury at the way live anthrax had been released just a mile from the Scottish mainland.

The one recorded outbreak on the latter – which led to the deaths of between 30 and 50 sheep, seven cows, two horses and three cats – was blamed on a animal carcass being dumped from a Greek ship which was passing the area.

But, by the end of the war, residents fumed that Gruinard had been burned, poisoned and abandoned and left in a state where nobody could go near it.

A few years later, MoD scientists began an extensive programme to clean up Gruinard Island and, by 1990, the site was once again declared safe, although there was never any indication as to what became of the missing 300lbs.

And what of the Dark Harvest Commandos? They were never found and left a last pithy note pinned to the door of the Scottish Office in Edinburgh on December 7 1981 to confirm they had ended their campaign – “for now”.

Their identity remains a mystery, although they were clearly well-organised and had the sense not to harm members of the public during their protests.

Journalist Iain Macdonald was among those who talked to people in Scoraig, a small, off-grid, anti-establishment collective, who lived close to Gruinard.

But, although some of their members were put under the microscope, nobody was ever charged with any offence and, the longer the matter went on, the more sympathy was expressed for the work of the environmentalists.

Mr Macdonald said: “Dark Harvest put that story front and centre [in the media] – and they succeeded in putting the spotlight on what was, when you think about it, an absolute scandal”.

The film-maker John MacLaverty has spent a long time bringing the myriad strands of the story together and has amassed many different theories.

He said: “The story of Gruinard Island has almost been forgotten now, and the mad tale of the Dark Harvest commandos is a mystery within a mystery.

“Gruinard Bay is an absolutely stunning place to film in, and nowadays filled with camper vans winding their way around the North Coast 500.

“The brochures will tell you that it’s a quiet and peaceful place – but if the scenery could speak, it would tell a very different tale.”

The MoD responded to the programme with a carefully-worded statement.

It said: “Gruinard Island was decontaminated and deemed safe in 1987. As part of the sale of the island in 1990, the MoD agreed to undertake further work, if necessary, within 150 years of its sale.”

No cause of death has ever been identified in Mr McRae’s case.

- The Mystery of Anthrax Island is on March 1 on BBC Scotland at 10pm.