It was the festive news nobody in the Western world wanted; the Russian invasion of Afghanistan on Christmas Eve in 1979.

As a teenager, I could tell from the anxious looks on my parents’ faces that this was yet another military foray with the capacity to spark a global conflagration and the potential to escalate into nuclear war.

If you were a Cold War baby, born in the 1960s or 1970s, such conflicts were part of your existence, a rites-of-passage to be negotiated with a queasy smile.

John F Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev, Richard Nixon and Leonid Brezhnev, regularly flung insults and issued threats at each other from both sides of the Iron Curtain, the Vietnam hostilities raised the temperature to near breaking point and we became used to slogans which chilled the blood. “Better red than dead” was the mantra for those who were prepared to irradiate the Earth to defeat Communism.

But even for those of us who found solace in the creation and campaigning of CND or lived in places such as Dundee, Fife, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Shetland or the Western Isles, whose councils all declared themselves to be “Nuclear-Free Zones”, the spectre of the devastating mushroom clouds which had enveloped Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 was never far from our minds.

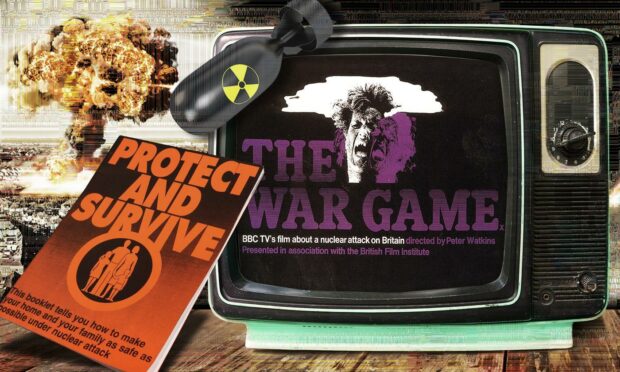

When film-maker Peter Watkins produced a terrifyingly bleak documentary The War Game in 1966, which depicted a nuclear holocaust and its corrosive, cancerous aftermath, the programme sparked such consternation within the BBC and government circles that it was pulled from the schedules.

The corporation argued that “the effect of the film has been judged by us to be too horrifying for the medium of broadcasting”.

But many of eventually saw it in bootleg copies – it’s now on YouTube – more than a decade later and its impact was profound. In Watkins’ eyes, there was no escape from radiation fall-out, the collapse of society and its infrastructure and the slow, lingering demise of those who survived the initial blast.

Troubling times

And, following the Soviet incursion and hawkish sabre-rattling as we advanced into the 1980s, it became a scenario which seared our brains.

As the decibel level and bellicose rhetoric increased between Washington and Moscow, these were troubling times for anybody planning for the long term.

Yet, looking back, there was also a sense of fatalism about the many things we couldn’t control and a gallows humour which left us laughing derisively at some of the more ludicrous aspects of the propaganda machine.

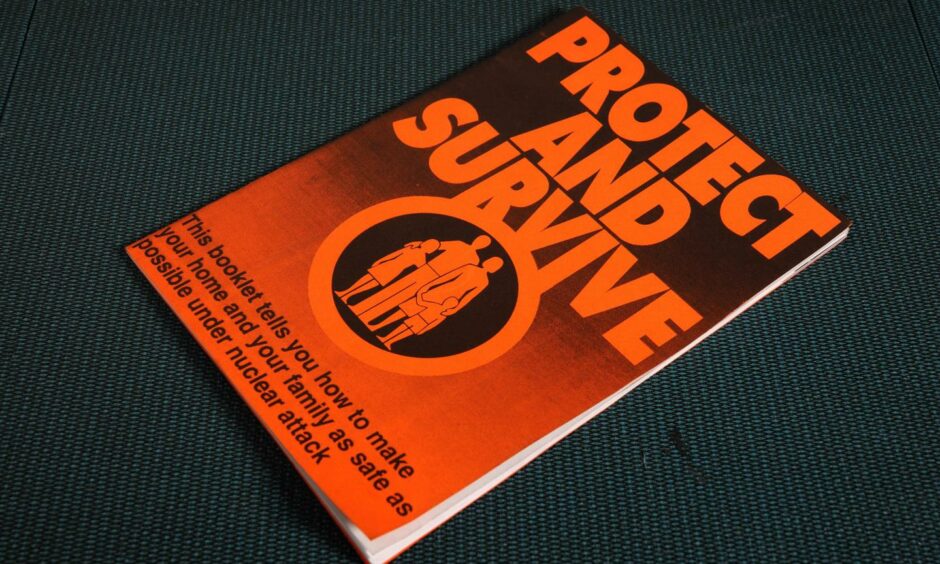

Nothing was more ripe for satire than the government’s Protect and Survive initiative which was supposed to advise the public on how to deal with the after-effects of a nuclear blast. If you were at school, this meant seeking refuge under your desk and putting your hands on your head – the sort of futile gestures which were subsequently mocked in The Simpsons.

For those unfamiliar with the venture, Protect and Survive (the first word was changed to “Protest” by those of us who considered ourselves lefties) was adapted for television as a series of 20 short public information films.

These were classified, marked Top Secret, and were only intended for transmission on TV channels if the government determined that the reality of a nuclear attack was likely within 72 hours.

But, as happened so often in these so-called cloak-and-dagger times, they were leaked to CND and the BBC, who broadcast excerpts from them on Panorama in March 1980, shortly after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the ridicule which followed showed that you can only take the public for fools so far before they know you’re treating them like dunces.

British actor Patrick Allan, who later became a voiceover artist for the comedy series’ Vic Reeves Big Night Out, The Smell of Reeves and Mortimer and Shooting Stars, was chosen as the narrator for the grim films and was subsequently described as “the calm, clipped vowels of a male announcer, advising how to build shelters, avoid fall-out, and how to wrap up your dead loved ones in polythene, bury them, and tag their bodies.”

But he admitted years afterwards that the assignment had nagged away at his conscience, given the often surreal statements he had been asked to read out.

And therefore, when Frankie Goes to Hollywood recorded their smash-hit single, Two Tribes in 1984, Allan, who narrated the first series of Blackadder, came up with a cunning plan to spout gobbledygook on the track, including: “Mine is the last voice you will ever hear. Do not be alarmed”.

James Cameron

In 1980, I sent a letter to the renowned Dundee-born journalist, James Cameron, who had previously worked at DC Thomson and had been a witness to not one or two, but three different nuclear explosions.

I asked him if he was concerned about tensions being ratched up between the superpowers and posted it off to the Guardian, never expecting a response.

Yet, within a few days, he had replied in spidery handwriting with the same mixture of silk and steel which characterised his writing and the words were sufficiently memorable that I have never forgotten them.

James told me: “You are far too young to be living under the shadow of the bomb. Go out, enjoy yourself, make your voice known if you want with CND or one of the other protest groups, but for heaven’s sake, don’t despair.

“I’m an old man now [he died in 1985], but I’ve always thought that nuclear annihilation wouldn’t be too bad if I was lucky enough to be directly underneath the bomb when it exploded. That would be all over quickly.

“But you can’t spend your life in fear, or you will turn your face to the wall. The Cold Warriors are old warriors and I have much more faith in the young. Please accept the good wishes of an old bomb bore, and I wish you well.”

Sporting dilemma

These were complex times, but that message reverberated loudly. It still does.

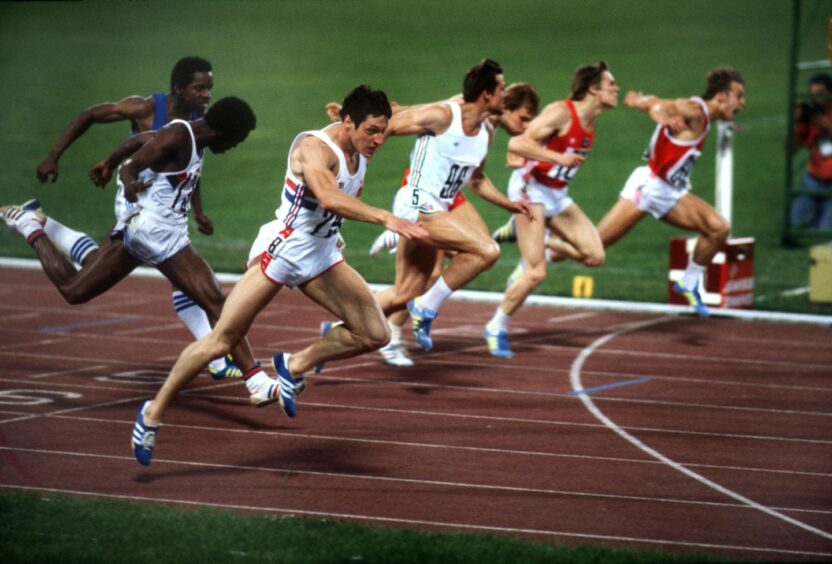

In the sporting world, Allan Wells surged to gold medal glory in the 100m at the Moscow Olympics, becoming the first Scot to claim a sprint triumph since Eric Liddell of Chariots of Fire renown at the Games in 1924.

Yet, in the build-up, he was sent pictures of dead Afghan children by the government, which tried in vain to persuade the athletes that they would be lending credibility to the Russian regime if they participated.

This led to the ridiculous spectacle of the BOA’s Dick Palmer walking around the Moscow arena carrying a pole without a British flag.

As Cameron added: “Margaret Thatcher expressed her Afghan horror by demanding a boycott of the Olympics, while presiding over a government whose traders and businessmen never had it so good in the Soviet Union. Does anybody else think this is sheer hypocrisy.”

Some things haven’t changed in 40 years – some things probably never will.

More like this:

How the north-east of Scotland became a target for the Stasi at the height of the Cold War

Military maps show how the German and Russian armies knew all about Aberdeen