Prisoner of war camps are not widely considered the greatest of places but children of the inmates look back on the one near Alyth with warmth.

One of these is Leven man Ronnie Kimmel, who is actually grateful that his German father Alwin was held at the Balhary PoW camp two miles south of the Perthshire town.

It meant that Ronnie would come to enjoy the best of both worlds – a life in beautiful Blairgowrie while retaining close links to his German roots.

All while safe in the knowledge that his father rather enjoyed himself while in supposed captivity at the tail end of the Second World War.

“My dad had really, really fond memories of how he was treated by the guards,” says Ronnie.

“He was well-known and liked in Blairgowrie and in the local pubs.”

In this feature we talk to the sons of inmates who enjoyed their time at the camp and the grandson of a local man who struck up a lifelong friendship with a Balhary prisoner. We also describe the conditions at the camp while it was in use, and how it looks today.

The feature is split into the following sections:

- Camp background

- Prisoner Alwin Kimmel

- Video of former Balhary camp in 2022

- Prisoner Friedrich Kehrer

- Local man Percy Caroline

Camp background

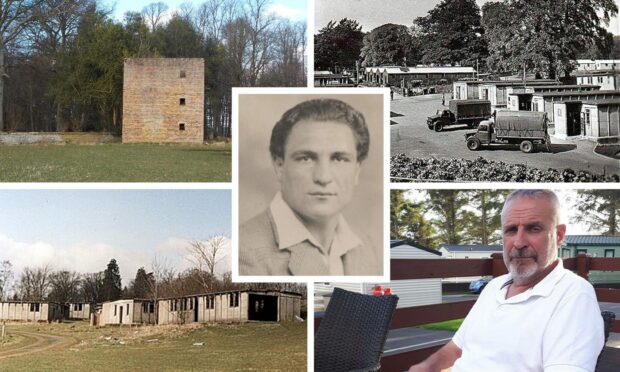

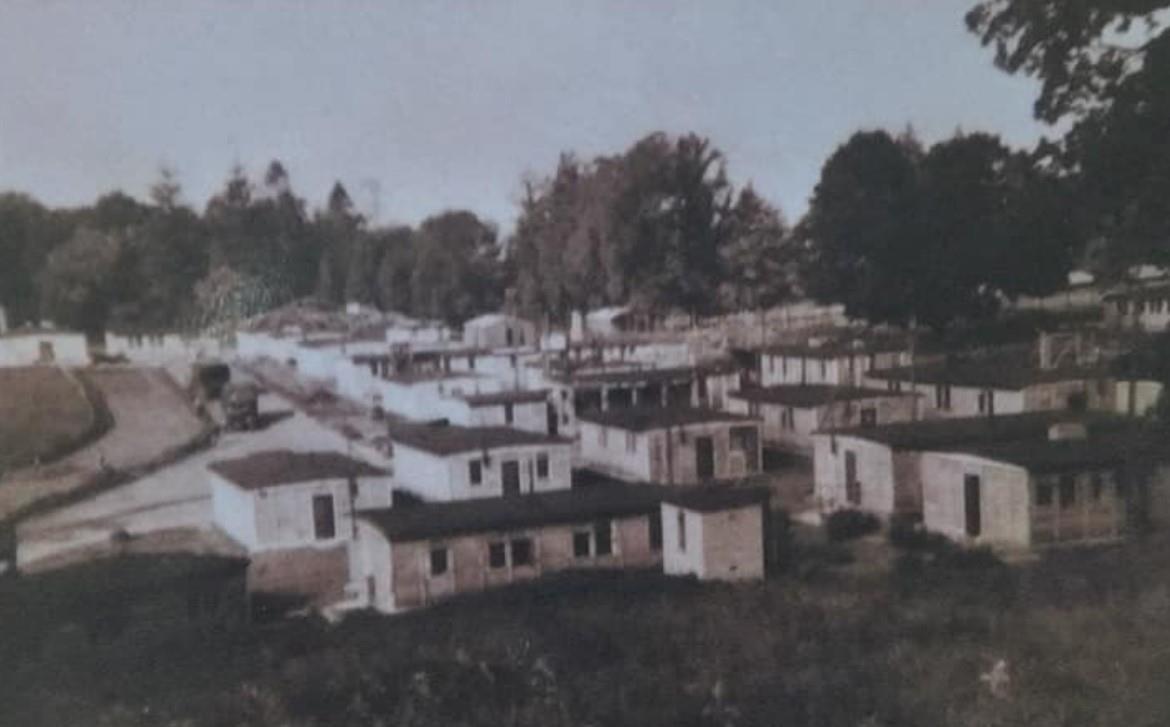

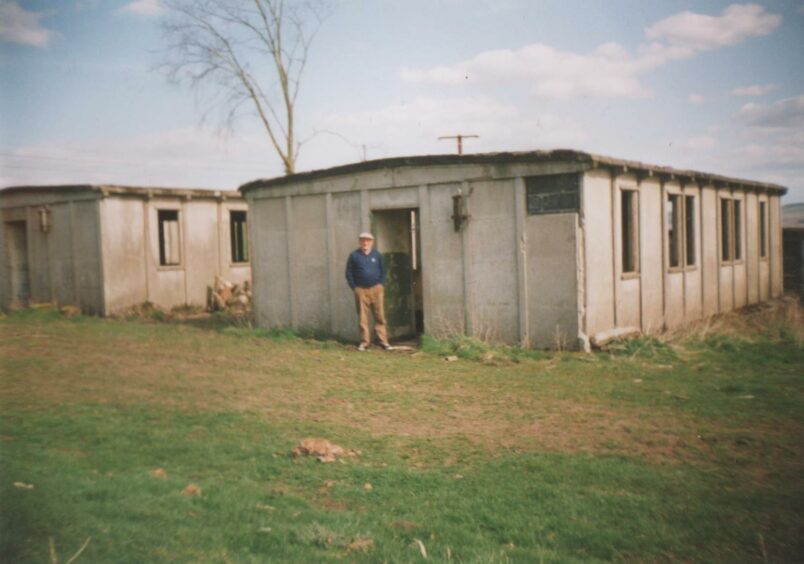

All that remains of the Balhary prisoner of war camp is a single water tower – without a water tank – on the edge of a wheat field close to Balhary house.

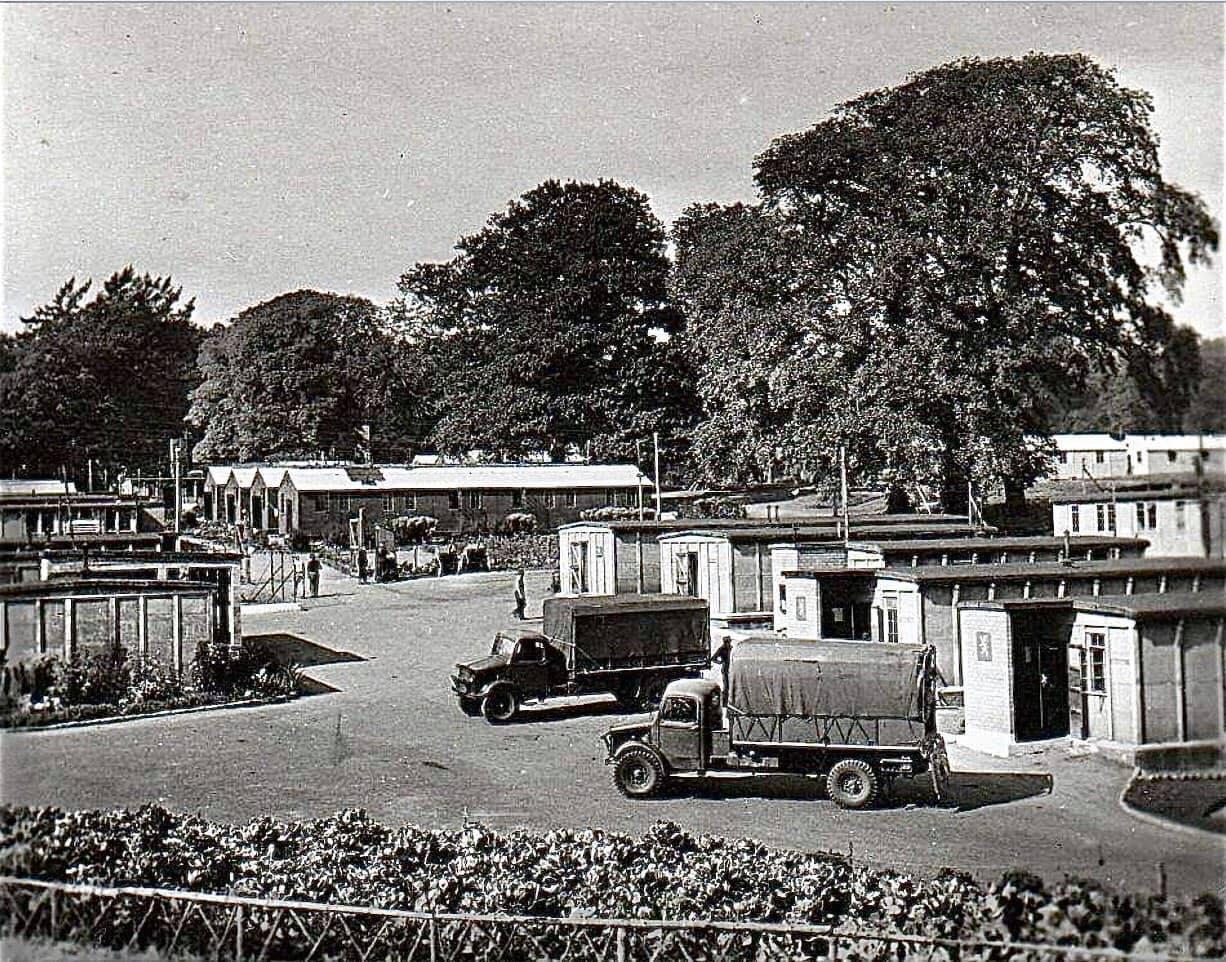

Back in the 1940s it housed a maximum of 800 prisoners – initially Italians, then Germans from early 1945 – in removable wooden and prefabricated huts.

After the war it was used for many years as a farm work camp for displaced people who could not return to their homelands in Eastern Europe.

The buildings survived until the 1990s, when everything bar the water tower was removed.

Prisoner Alwin Kimmel

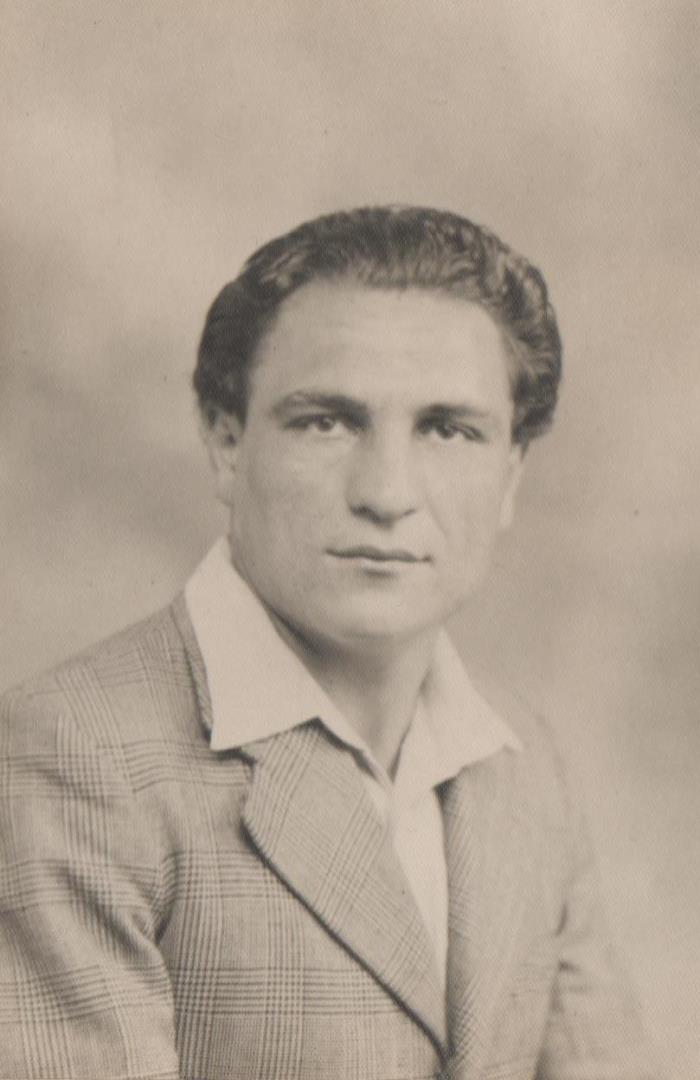

Alwin Kimmel was born in the Rhineland-Palatinate town of Jockgrim, 11 miles from the French border, in January 1927.

As the eldest he was the only one of four siblings called up for battle. In 1944 the 17-year-old joined the German heavy tank battalion.

He was captured by US soldiers at the Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes region of Belgium and was shipped off to the Deep South where he picked cotton at a PoW camp.

Towards the end of the war he was transported to the Balhary camp, between Alyth and Meigle.

‘The guards used to give him money’

“Believe it or not he had fond memories of Balhary,” says Ronnie. “He said the Americans weren’t as friendly as the camp guards in Scotland.

“The guards used to give him money and a list for him to walk into Alyth and he picked up sweets and food before coming back to the camp.

“He was working on local farms as well.”

Strictly speaking, he was not allowed to leave the Alyth-Blairgowrie area but he became friends with at least one local resident who broke the law to take him to a Dundee football game.

“It shows there was no ill-feeling towards lads they fought against during the war,” says Ronnie.

‘I realise how lucky I am’

After the war ended Alwin was so taken by the local area that he stuck around, working for farmer Charlie Mann on land in Blairgowrie’s Balmoral Road that is now housing.

Here, he met Nora Hamilton who was working at a nearby mill. They got married, stayed in Blairgowrie and became parents to Linda in 1950.

Four years later the family moved to Alwin’s hometown of Jockgrim with the intention of staying put.

Ronnie was born in 1954 and all was settled until Nora returned to Blairgowrie in 1960 for a holiday and decided she no longer wanted to live in Germany.

Six months later the family were back living in the Perthshire town, first in George Street and then in Myrtle Park.

In his working years Alwin helped build Backwater Reservoir and was a mechanical fitter at Michelin in Dundee. Nora was a cleaner at Blairgowrie High and Rattray Primary schools.

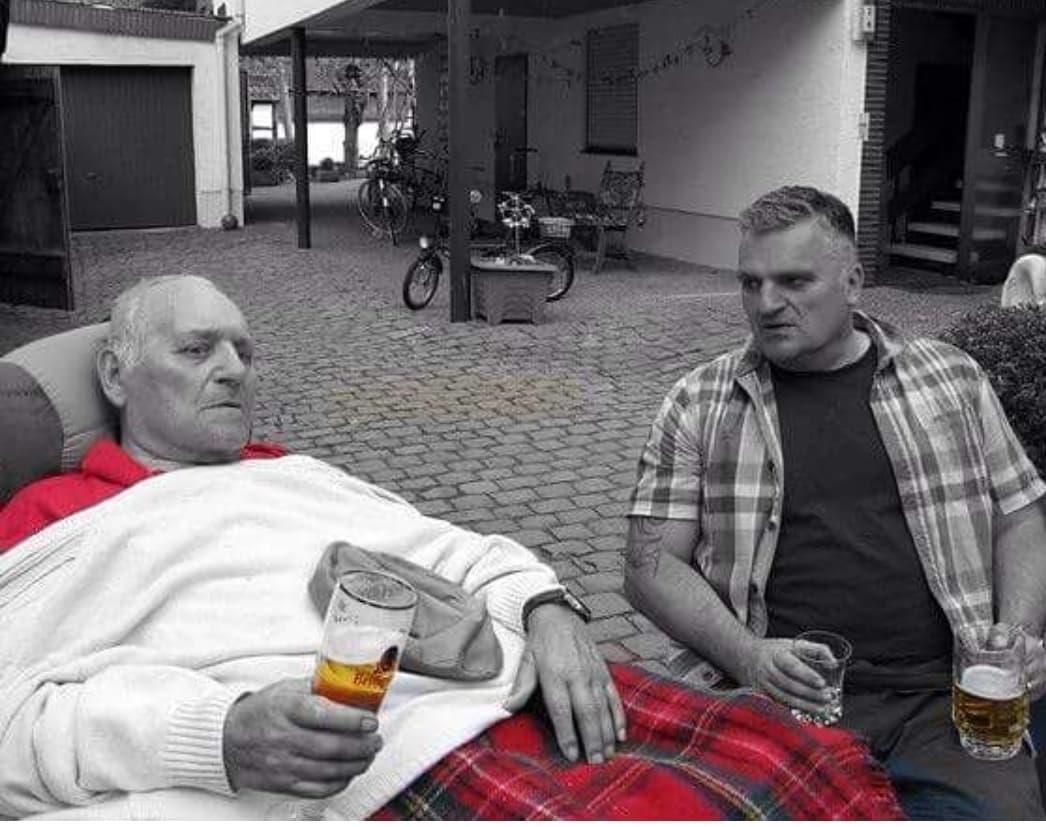

In 1981 Alwin and Nora moved back to Jockgrim while Ronnie stayed in Scotland, where his jobs included a CID officer in Fife and a private investigator.

Aged 65, Ronnie currently works at Diageo‘s Johnnie Walker whisky bottling plant in Leven. Alwin passed away in Germany in 2013.

“I realise how lucky I am,” says Ronnie, who classes himself part-German.

“I grew up in a great place like Blairgowrie and I have a lot of friends here but being able to go back to Jockgrim means I have the best of both worlds.”

Video of former Balhary camp in 2022

Prisoner Friedrich Kehrer

When Friedrich Kehrer arrived at the Balhary PoW camp in early 1945 there was one thing that created an abiding memory.

“It was the smell of bread baking,” says his son Fred. The unmistakable aroma had come from Italian prisoners who were being moved on as the Germans, including Friedrich, arrived.

“Maybe the Italians were taken to another camp,” Fred adds, “because the Germans and Italians were never together.”

‘He managed to get a boat to Britain’

Friedrich was born in 1925 and grew up in Stockstadt am Main in the Bavarian district of Aschaffenburg, which happens to be twinned with Perth.

He was called up to the German army at the age of 18 and trained to be a paratrooper but ended up spending a year ‘marching’ in France.

The following year he was deployed in the Netherlands as a ‘spotter‘ but was captured by Allied Polish soldiers in December 1944.

Friedrich was taken to Belgium where he was about to be sent to America. But he was concerned about the prospect of drowning in the Atlantic.

“There were other platoons heading to Britain and he felt there was a lot of water between Belgium and the US so he managed to get a boat to Britain,” Fred says.

“On Christmas Day 1944 they came across the English Channel in a cattle boat. He says that was the most scared he felt throughout the war because of the chance of sinking.”

‘Many farmers stayed in contact with the prisoners’

After arriving at an English port some of the German prisoners, including Friedrich, were taken to Scotland.

He was in a group that arrived at the former Alyth Junction Railway Station.

“From there they marched to Balhary,” Fred says. “It must have been some sight to see them all marching down the street.”

Once installed, prisoners worked at local farms during the day and at night returned to Balhary, where there was a shop at which prisoners could use “camp money” to purchase goods.

“They were respected by farmers because they were hard working and many farmers stayed in contact with the prisoners until their death.”

‘They didn’t punish them’

The camp owners also went against official protocol to help the inmates.

“If anyone was caught stealing anything – perhaps the odd hen to eat – the police locked them up in the prison on the site,” Fred says.

“But when they went away the chap on the site would let them out again – they didn’t punish them.

“My dad, and two or three others, used to go through a hole in the fence and head up to Alyth for chips.

“As long as there was no trouble and they got back before roll-call nothing was said.”

Patches to identify prisoners

In the first few post-war years there was a transitional period in which the prisoners were permitted to work on local farms but could also stay at Balhary if they so desired.

They were also only allowed to travel a short distance on local buses – a rule made possible by the sewing on to clothes of patches that identified them.

“They wanted to go to Dundee and got around this by getting off the bus early and then getting on another one to the city,” Fred adds.

Horse death tragedy

By 1947 Friedrich had taken up a post threshing corn at Dron Farm in Longforgan and it was at nearby Snabs Farm where he met Mary Clark, whose job was milking cows at neighbouring Northbank Farm.

They soon moved in together.

Mary, who was in her early 20s, had a son, John, whose father Jock Clark was killed by a horse while working at Dronley Farm in Angus. When they got married later in the decade Friedrich still had to notify the police.

The couple soon added son Martin, now 72, and daughter Irene, now 66, to their family. Fred, now 62, was born in 1960.

The family moved around, with Friedrich working at various farms in Coupar Angus, Auchterhouse and Errol before he settled into a job at Baledgarno Farm in Rossie Priory, Inchture, where he worked for 27 years until 1986.

The couple moved to Glencarse, where Mary passed away in March 1997 and Friedrich died in October 2019, aged 94.

‘They looked after him and he never complained’

Fred settled in the Abernyte area. He is a self-employed joiner and father to Lee, 37, Dean, 34, and Sally, 28.

Fred has only been to Germany once but is in contact with cousins in the country.

He says: “I can’t remember dad telling me any bad memories about his time at Balhary.

“They looked after him and he never complained about being cold in the huts.

“He used to work on the thrashing mills and the prisoners were meant to sit outside the farmhouse while the farmers were being fed.

“The farmer noticed dad was not with them and told him to come in and ‘eat with us’.

“Dad said some people wanted to escape the camp but many others were content to be out of the war. They were warm, getting fed and it was not overly strict.”

Local man Percy Caroline

It was not just the prisoners who looked back on Balhary with fondness, but the locals too.

One of these was Percy Caroline, who lived in Burrelton.

He served in the Seaforth Highlanders in the First World War, getting a gunshot wound in his lung in 1916 and thereafter being sent to guard German PoWs at a camp in France.

During the Second World War Percy was an officer in the Wellbank Home Guard and his day job was a greenkeeper, where he met Balhary prisoner Herbert Fillinger who was allowed out of the camp to work at the bowling green.

The pair struck up a lasting friendship, with Herbert even staying in Percy’s home occasionally.

Guard and prisoner ‘shared a special bond’

Herbert was a Luftwaffe airman who was shot down over the UK, and though he suffered burns he had recovered enough to work.

Dundee man Stewart Ross, one of Percy’s four grandsons, said: “He and my grandad became quite close friends – I imagine veterans share a special bond, despite the fact that both men had been injured by the actions of their enemies during two different wars.”

Herbert was released in 1947 and sent a hand-made thank-you card to the Caroline family when he got home to Neustadt in the Black Forrest.

‘He kept in touch for years after the war’

“He kept in touch for years after the war, sending cards for birthdays and the like,” adds Stewart, 61, who is now retired after working as a features writer at DC Thomson.

“My grandad actually travelled all the way to Germany to visit him once.

“My grandad died when I was quite young and because he was in Scotland and I grew up in England, we didn’t see him very often but I picked up a lot of stories from my mum.

“The ultimate irony is that my grandad had four grandsons, I’m one of them. The youngest joined the army in the 1980s and was sent to Germany.

“He’s been out of the army for many years but he stayed and settled in Germany and is still there – and his own son is now serving in the Germany army.”

Conversation