They were two actors whose charismatic personalities earned them stardom in the Swinging Sixties.

Sean Connery was the original James Bond, the shaken-but-not-stirred scourge of villains lurking in secret lairs with thoughts of world domination; Robert Shaw was the classically trained performer who fancied a crack at playing 007 but spent most of the decade cast in supporting roles.

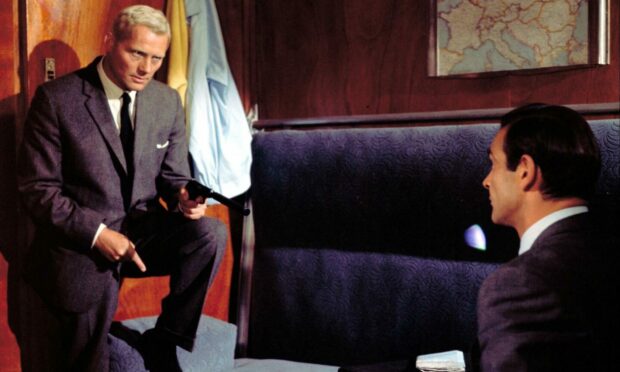

The two men were friends but also rivals so there was no need to ramp up the tension when they spent hours shooting a famous fight sequence in Terence Young’s From Russia With Love.

But their paths intertwined throughout their lives as their fortunes waxed and waned.

After his first stint as Bond, for instance, Connery struggled for a while to shake off his reputation as the wise-cracking agent with a licence to kill.

Shaw, in comparison, hit the big time in the first half of the 1970s when he appeared in The Sting, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three and, most famously, Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, en route to becoming a smorgasbord for a shark.

Both men responded in different ways to their childhoods in Scotland.

Connery grew up in a loving family and spent spells as a milkman in Leith, a lifeguard in Portobello Baths and a muscleman before treading the boards.

He was confident in his own skin, a lad o’pairts with sharp financial acumen who never needed to shed his Scottish accent, whatever part he was playing.

Orkney outcast

What a contrast with the brooding, introspective Shaw, who went to Orkney with his parents as a child and felt like an outcast in Stromness even as his troubled father – a doctor – battled alcoholism and eventually killed himself.

And although he tried his best to avoid going down the same route, the bottle caught up with him, along with a trail of debts and endless strife with tax authorities, at just 51 in 1978; whereas Connery was poised for a revival in the ’80s that brought him Oscar glory in The Untouchables and he lived until the age of 90 before his death in 2020.

It’s a tale of two very different personalities that needs some unravelling.

Even a glimpse at their photograph albums reveals the difference between the duo. Connery was in his element, alongside The Beatles and Jackie Stewart, and mingled with golf’s biggest names as if he was 007 himself.

Artist Richard Demarco, at the time a student in Edinburgh who painted several early pictures of Connery, described him as “very straight, slightly shy, too, too beautiful for words, a virtual Adonis”.

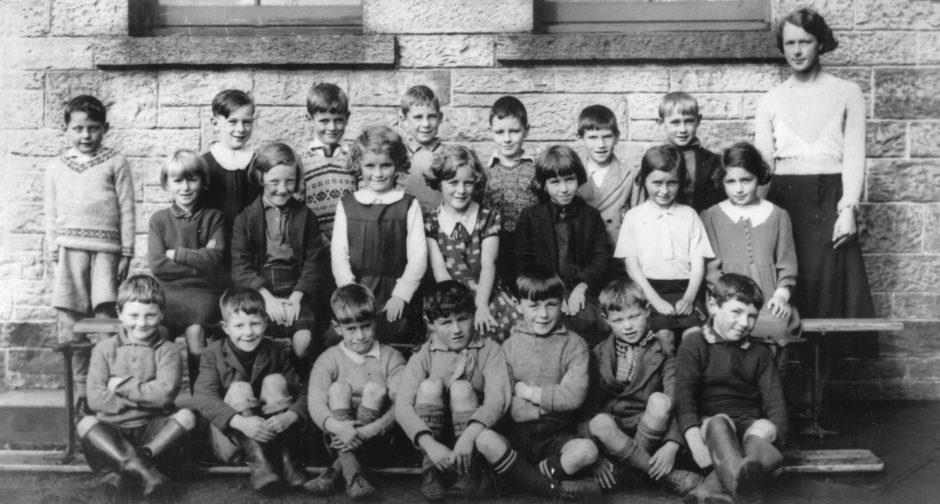

Whereas, there is a picture of Shaw with his classmates on Stromness and he strikes a mournful pose by standing apart from the rest of the crowd.

As his friend, John French, later recalled, the youngster had to grapple with being treated as an outsider after he arrived on the island.

He said: “The social climate was very different for the little boy. In Lancashire, he had been very much part of school life but in Stromness he was an outsider with a strange accent, who was called a ‘ferry-louper’.

“Dr Shaw was widely respected as a doctor but his drunkenness soon became a matter of public concern.

“With only 2,000 inhabitants, gossip spread quickly and the practice suffered accordingly.

“In 1938 Dr Shaw told his wife, Doreen, that he was determined to kill himself. She did not believe him, but one night, he went into his surgery and took poison. Robert was just 11 years old.”

It was a tragedy that scarred the actor for the rest of his existence.

No matter the glowing plaudits he gained for his memorable appearances on the silver screen – and the rave reviews he was accorded by US audiences after his roles in The Sting and Jaws in particular – his life was persistently blighted by scrapes, setbacks and set-tos, much of it linked to the demon drink.

Shaw became almost crazily competitive, constantly battling for top billing on film posters, and arguing about money and contracts; he was also driven by a need for children of his own and eventually fathered nine by his three wives.

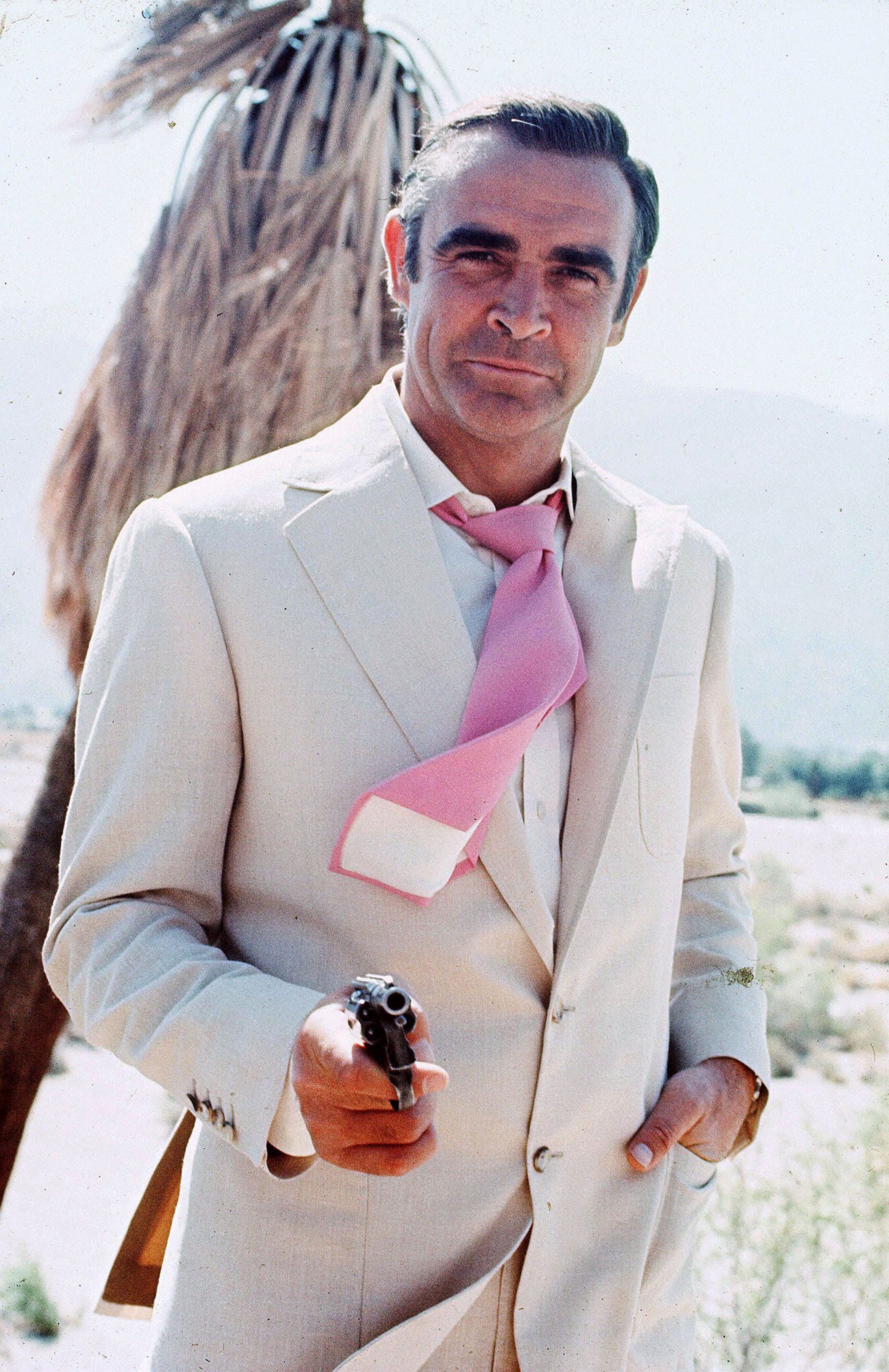

He looked enviously at the manner in which Connery, the canny Scot, negotiated a then-record $1.25m to return to his Bond role in Diamonds Are Forever in 1971; a pay cheque that enabled him to establish a charitable foundation and – just about – attend all the golf events he could organise.

Although Jaws has become a cinema classic in the last 45 years, the filming of Steven Spielberg’s movie was beset by problems, including the costs of shooting on water and the difficulties of operating a faulty mechanical shark – which explained why the monster was mostly (and sensibly) kept concealed.

But once audiences flocked into cinemas, the movie was soon acclaimed as a masterpiece and, finally, belatedly, Shaw found himself in a position where he could pick and choose his roles as offers flooded in.

One of the choices that fired his imagination was pitched by Dick Lester: the story of how Robin Hood and Maid Marian’s life unfolded after they had defeated the Sheriff of Nottingham and advanced into middle age.

As the director assembled his cast, there was a reunion between Connery and Shaw with Audrey Hepburn in a stellar litany of talent, which makes it all the more surprising that Robin and Marian was a box-office flop.

Renowned critic Roger Ebert was among those who thought the film worked best when Connery and Shaw – two men exhausted by decades of often senseless conflict – were in the same frame together, their joints aching, visibly fatigued by the thought of yet another bloody sword fight.

As he wrote: “What prevents the movie from really losing its way are the performances of Sean Connery and Audrey Hepburn in the title roles and a fine supporting cast. Robert Shaw comes over best, all grim and patient as the sheriff and he gives us a movie worth seeing”.

These people feel like real human beings. No longer young or full of the joys of spring, the only thing they have to look forward to is the past.

Sadly, by this stage, Shaw’s problems off camera were clouding his judgment.

Connery, who had acted with him in ITV’s Play of the Week in 1960 when they starred in The Pets – about two RAF pilots who are shot down, captured by an eccentric German and imprisoned in his cellar – reached out in friendship to his colleague, but gradually, inexorably, Shaw was moving beyond salvation.

As French wrote: “In July 1977, Shaw was offered the chance to play in a pro-am golf tournament, organised by Sean Connery and Sir Iain Stewart, the man who ran the charity set up from the proceeds of Diamonds Are Forever.

“It was an event which was being televised by the BBC and held at Gleneagles. Shaw agreed to appear and planned to go to Orkney after the match, the third wife he would have taken back to Stromness.

“But, over the next few weeks, he agonised about the decision. In August, he cancelled, telling the producer and Connery that he had another commitment – he did not.

“And he cancelled the trip to Orkney as well.”

Final act…

Just a year later, Shaw suffered a heart attack and died while on a motoring trip in Ireland. He had only turned 51 a few weeks earlier.

There was shock at the news among the wider public, but not those who were closest to him and had witnessed his spiralling decline.

But he was never forgotten in the streets of Kirkwall and Stromness and Archie Bevan was one of those who established a friendship with the young Shaw and paid tribute to him in a piece broadcast by the BBC in August 1978.

He recalled: “Robert was two classes below me in school, an unbridgeable gulf at that age. But he was a classmate of my cousin, Arthur Porteous.

“His schooldays in Stromness made an enduring impression on Robert. When I met him more than 20 years later, he recalled those days in vivid detail.

“He was able to name his classroom friends and enemies and he remembered the bitterness he had felt in the early days when he was ganged up on by a small clique – headed not by an Orcadian, but by an incomer like himself.

“He returned to Orkney in the summer of 1963 with his second wife, Mary Ure, the Scottish actress who had made her name as the long-suffering wife in John Osborne’s play, Look Back in Anger.

“I remember that my first meeting with Robert was on Stromness Golf Course. He was in a foursome with some members of the local club.

“His dark hair had been bleached to a startling Aryan blond, a remnant of his role as the villain in From Russia With Love, which he had just finished shooting.

“Of course, you’ll remember he came to a sticky end, at the hands of James Bond, but Shaw told me that he and Sean Connery were very close friends, and he had a great admiration for Connery’s ability as an actor.”

The admiration was reciprocated and it’s just a pity they never gained more opportunities to work in tandem.

Shaw was capable of forging great friendships with many people across the acting and literary world and became a cult hero when he moved to Ireland.

Those who met him still testify to how he was charming, charismatic and capable of terrific generosity – but he never acquired the knack of knowing when to say “Stop” once the drink started flowing.

In his case, sadly, it truly was like father, like son.

More like this:

Peter Alliss: My Bond with Sir Sean Connery at his beloved Gleneagles

10 years since Skyfall: Celebrating James Bond’s Highland heritage