The infamous Skarne area of Whitfield was a classic example of Sixties planning gone wrong.

Dundee Corporation wanted to tackle slum dwellings after the war and build new homes to tackle overcrowding in a city that was running out of space.

In 1952 a draft plan for the development of Dundee was drawn up by planning consultant Dobson Chapman that took three years to complete.

Greenfield land in the north of the city was selected for future development, in what would become known as the Whitfield estate.

Concrete blocks cost £8.5m

Inspired by Scandinavian models, particularly the work of Swedish company Skarne, Dundee Corporation awarded a contract for 3,500 homes to Crudens Ltd in 1967.

Crudens of Musselburgh was the British agent of the Skarne system.

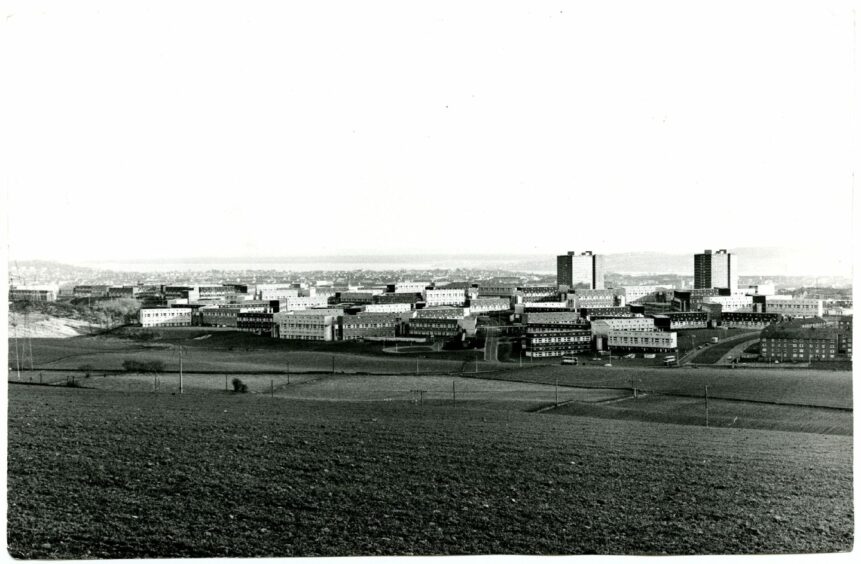

The high-rise concrete blocks of modular Swedish design cost £8.5 million and were finally completed in 1971 for a population of more than 7,000.

Seen from above, the Skarne area of Whitfield used to look like a honeycomb, made up of 130 distinctive deck-access maisonette blocks.

The development was supposed to be the last major part of the solution to Dundee’s slum clearance programme with miles of “walkways in the sky”.

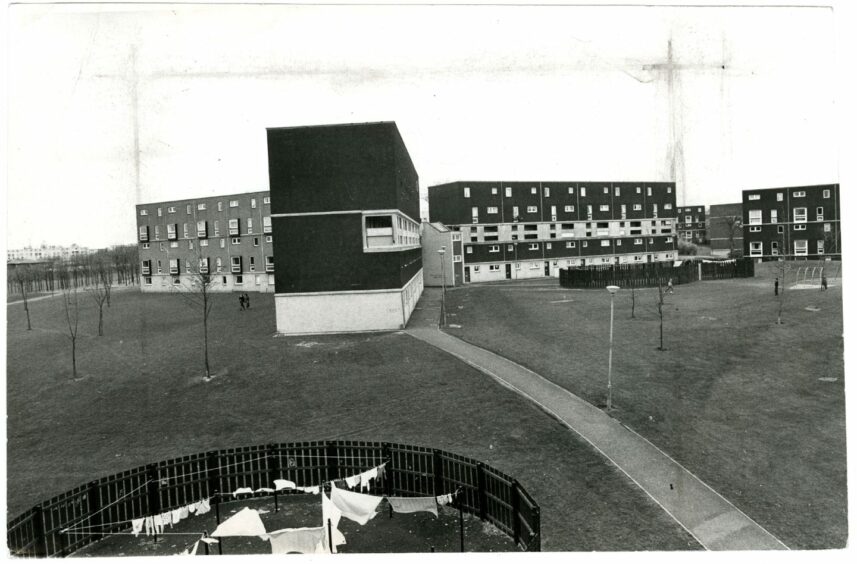

Instead, it became seen as a rabbit warren for crime, while there were complaints from families living in upper-storey homes without lifts.

Problems arose with lighting and poor doors and windows.

It was realised no-one wanted to stay in them and they were identified as hard to let by 1975.

Safety catches were installed on 1,583 of the windows in 1977 with grilles added to the raised walkways as the estate started to become a no-go area.

‘The area degenerated…’

Andrew Murray Scott, author of Modern Dundee: Life In The City Since World War Two, said: “As early as 1972 Whitfield was being described as ‘the great Dundee housing idea which has gone sour’.

“There was increasing reluctance to move there, even among tenants on the waiting list.

“There were various reasons for this. It was the most remote housing scheme and also the largest with 4,800 dwellings and a projected population of 11,000.

“It was expected that it would finally wipe out Dundee’s house waiting list, but 300 remained empty with some 200 still to be built.

“Even when tenants were found the turnover was rapid. The area degenerated.

“Vandalism and gang trouble, particularly at the shopping centre, intimidated the elderly.”

Not all of the scheme was problematic.

The south part, off Whitfield Drive, consisting largely of semi-detached dwellings, was popular, but the problem was the 2,500 Skarne dwellings in the north.

Between each group of five blocks was a ‘no-man’s land’ of grass and drying greens which often became a muddy swamp and was unsuitable for children to play on.

One of the most problematic areas was Dunbar Crescent, later known as Moonlight Alley, which broke records for the number of tenants who vanished from it, leaving considerable rent arrears.

In less than a year 50 families did a ‘moonlit flit’ from this street alone and eviction notices pasted on doors became a common sight.

“The Corporation’s Housing Study 1969–70 resulted in the shelving of the remainder of the Skarne-type dwellings, and at Kellyfield 300 low-density cottage-type houses were built,” Mr Scott said.

“A valuable, if costly, lesson had been learned.”

High unemployment rate

Barely 20 years after it was built, the Whitfield housing estate in Dundee was one of the worst in Scotland.

Its population had fallen well below capacity, its unemployment rate was a staggering five times the already high Dundee average and almost three out of every four households had an annual income of below £5,000.

One quarter of the available homes, mostly in the unloved Skarne blocks, were empty and were the frequent targets of vandals and fire-raisers.

Whitfield had become a shorthand term for urban decay and all the dispiriting economic and social problems that go with it.

In the mid-80s a council project started to look at ways to improve the Skarne and an architect and a sociologist from Dundee University came to interview the people who lived there.

‘A horse was my neighbour…’

The stories inspired playwright Tom McGrath to create a BBC2 programme following their lives in a fly-on-the-wall documentary.

When the funding fell through, though, he wrote a play centred on Coralie Burr and the last two years she lived in the Skarne.

Then 31, Coralie lived with her four children in a freezing two-bedroom flat in the Skarne blocks and she had a horse as her neighbour.

People would see it going up the stairs, although Coralie never found out who it belonged to.

“Life was busy, ” she said. “I was on my own with four boys.

“It was all-go all the time but it didn’t feel like that back then. We were cramped, living in two bedrooms.

“It was a concrete building as well. We only had two storage heaters – and one was near the front door. It was freezing.”

But the improvements promised in the council project never happened and Coralie was eventually moved to a bigger, four-bedroom property in lower Whitfield.

But Coralie remembered her days in the Skarne as mostly very happy.

She said: “The only time I wasn’t happy there was when I was having my first child. I moved in just before I got married.

“It was very lonely. The concrete made it seem soulless but the community grew around it.”

So bad had things become that in 1988 the Scottish Office stepped in, making the estate one of four in Scotland to be singled out for special treatment under the New Life for Urban Scotland project.

The others were Castlemilk in Glasgow, Ferguslie Park in Paisley and Edinburgh’s Wester Hailes, which was poor company to keep.

Most of the blocks were demolished in the 1990s and significant work has been undertaken to transform the neighbourhood.

More like this: