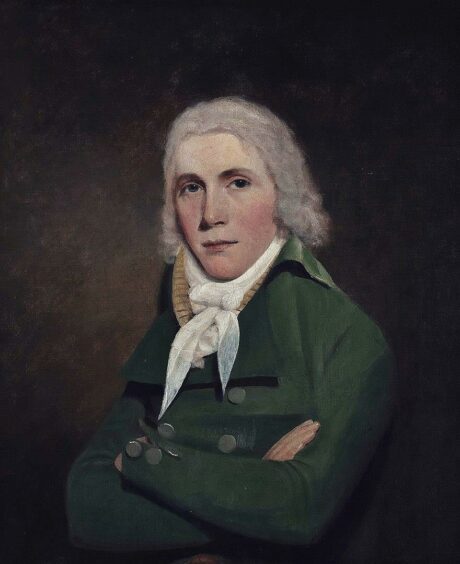

A young man from Fetteresso, Stonehaven, emigrated to York (now Toronto), Upper Canada in 1793, and became a highly successful merchant, philanthropist, magistrate and general pillar of the community.

So far, so unremarkable.

But Canadian society turned savagely on Alexander Wood during his lifetime, and continues to do so, more than 200 years later.

Wood is thought to have been gay, and this brought upon him a scandal which ended up overshadowing the rest of his life, and legacy.

Rape case

In 1810, in his capacity as a magistrate, Wood, now 38, was investigating a rape case.

The plaintiff, a Miss Bailey, apparently told him that a young soldier was the culprit, that she couldn’t identify him, but that she had scratched his genitals during the attack.

Wood separately told several young soldiers of the accusation, and to clear their names, the men dropped their pants for Wood’s inspection.

They were all deemed innocent by this test, and the attacker was never found.

Word spread, and it wasn’t good.

Despite never having been accused of impropriety, the fact that Wood was a ‘lifelong bachelor’ was enough to spark rumours that he’d invented the whole tale as an excuse to molest the soldiers.

The rumours intensified when he refused to divulge Miss Bailey’s real name, on the basis of protecting her honour.

It’s hard to overstate how important that would have been in those days.

Now Judge William Dummer Powell, once a friend, demanded an explanation.

Wood’s answer didn’t lay the scandal to rest.

‘Ridicule and malevolence’

He wrote: “I have laid myself open to ridicule and malevolence, which I know not how to meet; that the thing will be made a subject of mirth and a handle to my enemies for a sneer I have every reason to expect.”

His business was hit hard, and he was branded a ‘molly’, 19th-century pejorative slang for a homosexual, and publicly mocked as ‘the Inspector-General of Private Accounts’.

He faced an investigation into abuse of power, and Judge Powell made it clear that Wood’s problem would only disappear if he went along with it.

Wood returned home to Stonehaven, but went back to Canada two years later to fight in the War of 1812.

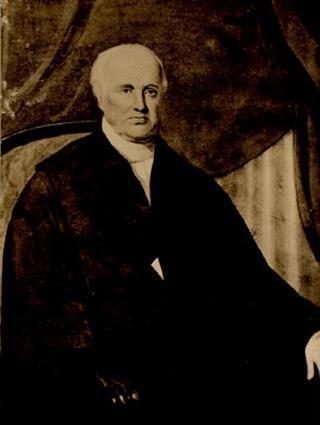

Still simmering, Judge Powell published a pamphlet resurrecting the scandal, but Wood sued for libel, and won.

The tables had turned.

Wood was implicitly cleared of the Miss Bailey accusations, and Powell’s relentless persecution of him led to questions about his own reliability.

Now Wood was embraced by Toronto society and carried on with his charitable and philanthropic work.

He served as an acting director of the Bank of Upper Canada, sowing the seeds of what two centuries later would become another undoing for the boy from Fetteresso.

In 1827 he bought 50 acres of lands in Toronto, referred to as Molly Wood’s Bush throughout the 19th century.

Gay village

It would become part of the gay village in the city.

Wood returned to Woodcot, Stonehaven in 1842 and died there two years later, at the age of 72.

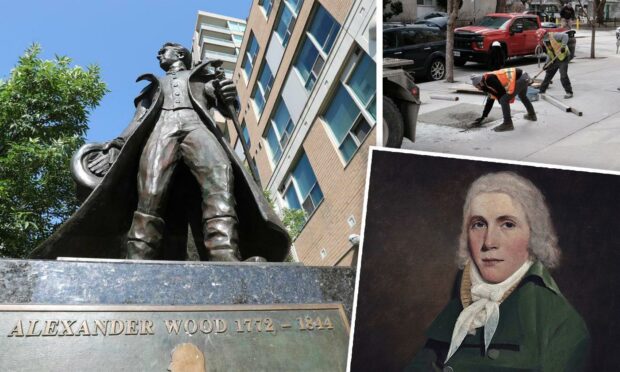

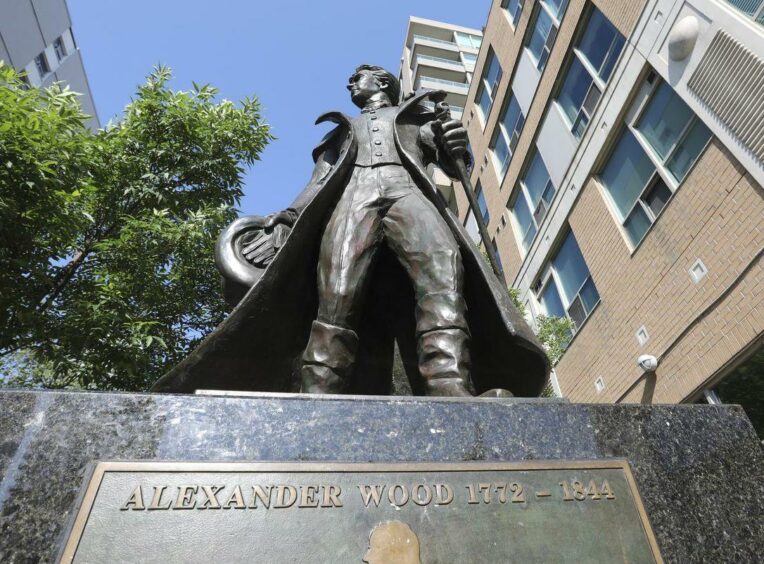

Fast forward to 2005, and a large and rather flamboyant bronze statue by Del Newbigging was put up in Molly Wood’s Bush to honour Wood as the forefather of Toronto’s modern gay community.

The chairman of the local business association behind the statue, Dennis O’Connor said: “Alexander Wood was philanthropic, he fought in the war of 1812, was the treasurer for all the charitable societies of the day, plus a staunch member of the church.

“These are the big things that connect him to us.

“As a gay hero, we have found our man.”

But Wood’s memory would not be allowed to rest in peace.

Earlier this month (April 4, 2022), the statue was abruptly taken down by the authorities.

Wood’s memory was now enraging members of the LGBT+ community who said such a non-transgender, white, gay man, a settler, was in fact an out-and-out oppressor, and the statue represents a colonial, imperialist aesthetic.

Philanthropic work deemed dishonourable

Moreover, Wood’s philanthropic work was wheeled out as a mark of dishonour.

When he worked with the Bank of Upper Canada, he had helped fund St John’s Mission residential school, at the personal request of a native American chief.

He was a founding member of an organisation known as The Society of Converting and Civilizing the Indians and Propagating the Gospel Among Destitute Settlers in Upper Canada whose aim was to raise money for ‘Indian Mission Schools’.

St John’s Mission would go on to become the Shingwauk Industrial Home, and later Shingwauk Residential School.

Long after Wood was dead, scandal emerged around Shingwauk Residential School where children were found to have suffered horrific abuse.

Those who had fought and fund-raised to have Wood’s statue put in place, now turned against him, saying they didn’t know about the residential schools.

Brian Bradley of the Toronto Star reported on April 5 2022: “Without any consultation with community members, recent communication with the city or any advance public notice, the statue was pulled into a dump bin, with the hole in the ground where its granite podium stood filled with concrete.”

Other voices emerged to say the statue should never have happened in the first place, including Steven Maynard, a social historian and professor at Queen’s University.

He said: “We pretty much always knew the Alexander Wood story, hence the reason why some of us, myself included, objected to this happening in the first place.”

Gay rights activist and resident Susan Gapka said: “As a gay icon it doesn’t relate.

“It is not inclusive of women, racialized people, indigenous people or of trans people.”

You might enjoy:

Life of transgender Aberdonian aristocrat set to be made into TV series