William Goldman was the Hollywood screenwriter who best described the problem with concocting a recipe for a hit movie.

He said: “Nobody knows anything….not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work. Every time out, it’s a guess and, if you’re lucky, an educated one.”

Yes, he enjoyed spectacular success with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, All the President’s Men, Marathon Man and The Princess Bride. But there were other misfires and might-have-beens which amounted to less than a hill of beans and led to what he described as his “leper period” in the industry.

It’s 20 years ago this week since the release of a film which seemed a sure-fire success.

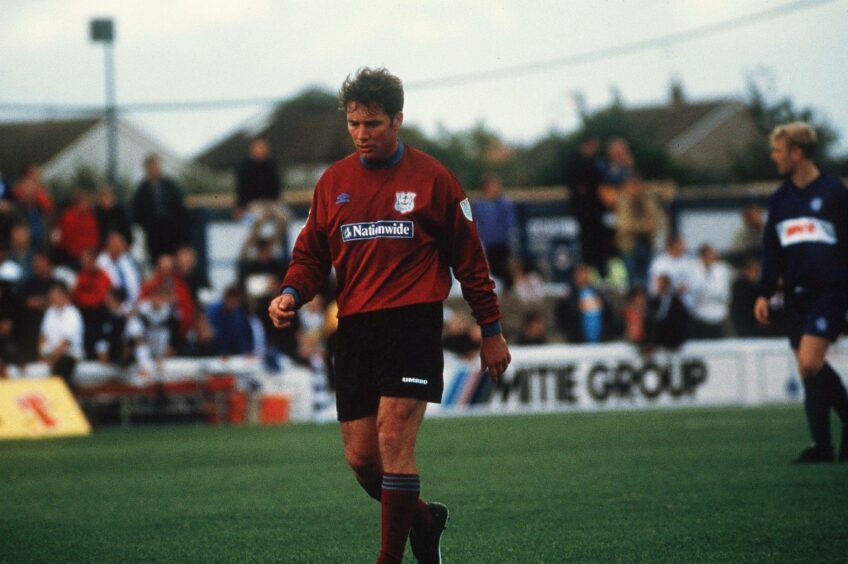

It had Oscar-winning stars in Robert Duvall and Michael Keaton, a big beast of Scottish cinema in Brian Cox and an acclaimed acting turn from Ally McCoist, who was cast as a gifted, but troubled Celtic striker.

It also promised a realism in its football scenes, given the involvement of the likes of Owen Coyle, Ally Maxwell, Didier Agathe and Derek Ferguson.

And Duvall went to the trouble of speaking to – and spending time with – Raith Rovers player-manager, John McVeigh, and listening to his accent. He told the press he wanted to get away from the stereotypes and clichés which kept cropping up in bad sports movies and create something better.

The film, which was shot across Scotland, including Kilmarnock, Dumbarton, Glasgow and Crail in Fife, was called A Shot at Glory and, on paper at least, it seemed to have all the right stuff to attract major audiences.

But, of course, football isn’t and never has been played on paper.

I still remember talking to McCoist about the project and, as usual, he was effervescent about the prospect of rubbing shoulders with Hollywood royalty. It didn’t concern him that, in taking the fictional role of Jackie McQuillan – a mixture of Charlie Nicholas and George Best – he would be guilty of sacrilege among those who regarded as him as Ibrox first, Ibrox forever.

“It’s just a role, isn’t it,” he told me at Rugby Park. “It has been a privilege to get to know Robert Duvall and he has really taken a shine to Scottish football. He’s working hard on getting things right. He wants this to mean something.”

The script, written by American Dennis O’Neill, who had previously worked on The River Wild with Meryl Streep, even attempted to weave some social commentary about the sectarian tribal divisions of the Old Firm, but it was clearly striving to be closer to a combination of Gregory’s Girl and Local Hero: another tale of wealthy transatlantic executives facing a massive culture shock when they met their Scottish counterparts at Kilnockie FC.

Unfortunately, for all concerned, they didn’t hire Bill Forsyth.

No drama when it’s all scripted

But there were problems. Lots of them. And, although Ally and Bob [Duvall] clicked off screen and achieved a nice chemistry on it, the movie never managed to find a way of rising above the central fault with these ventures: namely, how to bring sport to life when the ending has been scripted and the Cup final result decided months or even years before it arrives in cinemas.

There are exceptions. Field of Dreams was a triumph and Tin Cup a cut above most of the competition, and, although Will Smith is now regarded as a pariah in La La Land, his performance as the eponymous Ali, directed by Michael Mann, possessed enough shade to make it a good, but not great celebration of the boxer, who floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee.

But, as for football, it remains a mystery to capture it properly on celluloid, no matter the quality of the cast, crew or people involved in the screenplay. And that is even before we discuss Duvall’s difficulties with the leading role.

He certainly couldn’t be accused of not doing his research. The veteran luminary of such acclaimed works as Apocalypse Now, The Godfather, Tender Mercies, Network and the wonderful series Lonesome Dove, travelled to Scotland and met such luminaries as Jimmy Johnstone and Craig Brown, before spending plenty of time with McCoist and McVeigh.

He said at the time: “John is a tremendous character and a great motivator with an enormous amount of enthusiasm. I like him a lot.

“Then, there’s [the late Celtic maestro] Jimmy Johnstone. I watched him on video a few times and it was amazing. But, when I met him, I had to ask him to talk a bit slower because I couldn’t understand a word. I even named my Scottie dog Jinkie after him. He was something special, wasn’t he?

“As for Ally, he is a great guy. I knew he would be good for us the first time I met him. I wanted him immediately.” And the feeling was mutual.

Indeed, McCoist quipped: “Let’s face it, if Vinnie Jones can make it as an actor, then I must have a great chance of an Oscar.”

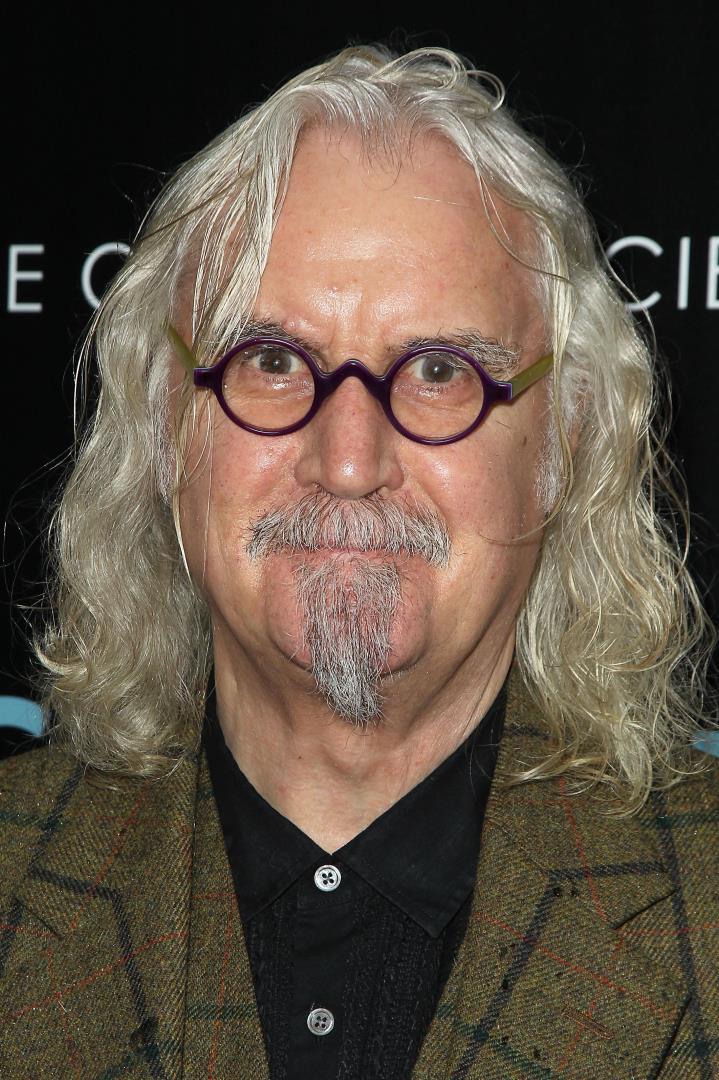

But there were cast changes and wholesale revisions. Alec Baldwin was slated to appear and there was even talk of Billy Connolly joining the action.

Yet, almost everything – the budget, the stars, the filming – was of sufficient quality that the producers could say: “There have been a few football movies in the past, but we’re in no doubt this will be the best you have ever seen.”

The trouble was that Duvall just couldn’t get to grips with the Scots language. At some points, he sounded like Sean Connery, at other times he veered into a strangled mix which hailed from Ayrshire, then Belfast, and his team talks – as he worked to inspire the Kilnockie squad during their Cup heroics – owed more to Rikki Fulton or the Krankies than Alex Ferguson or Jock Stein.

The Press & Journal said: “You don’t want to be critical of such an acting heavyweight and an undoubted legend of the big screen. But, if there are occasional flickers of the Scots dialect in Duvall’s confounding accent in A Shot at Glory, this one is up there with the worst of the worst.”

Even the actor himself later admitted the challenges when he told Variety: “I had to work on the accent because it’s like a foreign language. It’s like a little bit of German, a little bit of Scandinavian, a little bit of everything.”

There was nothing small-scale about A Shot at Glory’s ambitions. One story in August 1999 carried the headline: “Wanted: 50,000 screaming Scottish soccer [sic] fans to star in a Hollywood movie.”

And there were cameos from plenty of Raith Rovers and Airdrie players and members of the Scottish media after the climax, which built to a penalty shoot-out at Hampden Park with McCoist at the centre of the drama.

The critics generally panned it, but the Scotland and Rangers player was spared any abuse. Indeed, his performance left some wondering why it wasn’t the catalyst for a flourishing career on the silver screen if he had so chosen.

I sat down and watched the film again recently and it’s not terrible. You can see that money was lavished on the exteriors and care taken to make the football footage as close to reality as possible. And McCoist was impressive.

But the worst waste of the talent on show was casting Cox as the Rangers manager, instead of giving him the Duvall role. Just imagine how much more believable the whole story might have been if the Dundonian had embarked on some spectacular dressing-room diatribes – worthy of Logan Roy in Succession – to scare the Kilnockie team half to death.

Ultimately, it’s probably best regarded as a noble failure and a reminder that the best moments in football – Diego Maradona’s pyrotechnics against England in 1986, Paul Gascoigne’s goal against Scotland in 1996 or Archie Gemmill’s pirouette through the Dutch defence at the 1978 World Cup captured the imagination because they all happened spontaneously.

There were no directors crying “Cut”, no harassed extras wrangler setting up Take 15; just myriad supporters crying with joy or anguish at something which was unfolding in real time in front of their own eyes.

And no film will ever replicate that feeling of pleasure or pain.

More like this:

Rapper’s delight: When Succession brought Logan Roy, and Brian Cox, home to Dundee

The real-life Escape To Victory: How Dundee footballers survived a brutal German prison camp