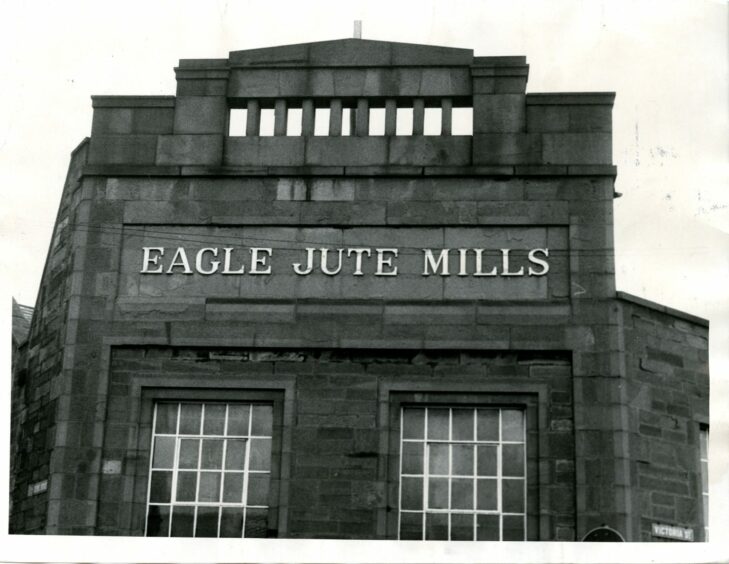

What became of the large wooden eagle that looked down on generations of Dundee jute workers?

At its peak, around 40,000 families were dependent on the jute industry and mills dotted the Dundee skyline in the mid-19th Century.

The eagle was made by a ship’s figurehead carver called James Law in 1864 and was the centre piece of the Dens Works Foundry on Victoria Street.

At its height, the Baxter family business employed 5,000 people.

The eagle was Law’s trademark.

The eagle took flight in 1930

Law ran his business from the three-storey foundry building and employed a number of skilled craftsmen to help carve figureheads for Dundee ships.

In those days, of course, there were many shipyards along the riverside.

The eagle moved when Dens Works Foundry was extended to become the main modern jute spinning plant for Low and Bonar Ltd in 1930.

It was the only new mill built between the wars.

It was described as “the finest in the world” after opening and occupied the site between Victoria Street, Dens Road, Lyon Street and Brown Constable Street.

The industry was hit by a series of booms and slumps before falling into decline in the 20th Century.

Eagle Jute Mills closed its doors in 1978.

What happened to the wooden eagle following its closure?

A spokesman for Low and Bonar in 1978 said it was sold to an undisclosed buyer.

“Well, actually, it’s been sold to someone,” he said.

“All the fittings have been sold and the premises are up for sale.

“The eagle was sold along with the fittings.”

So who bought the eagle?

“I don’t know,” he said.

“It’s not that I can’t tell you, it’s simply that I don’t know.”

All that is gold does not glitter

It was strange that such a well-known landmark should disappear so suddenly and the bird’s final nesting place was still being talked about in 1980.

At that time it was at least “alive”, if not looking too well, when a real-life Lovejoy walked into a Perthshire antiques store with the elusive bird.

Ian Imrie, of Imrie Antiques, Bridge of Earn, who was a member of the Civic Trust in Perth, said he was offered the monument but turned it down.

“It was made of timber and was very rotten,” he said.

“It had recently been painted with gold paint, which didn’t help much.

“I have no idea where it might be now.”

The Eagle building was the subject of several unsuccessful planning applications.

Ladbrokes wanted to take over part of the building as a new leisure complex and Dundee FC also considered using it for training purposes.

The former mill was bought by Tayside Plumbing and Building Supplies Limited before being filled up by various enterprises over the years.

But the wooden eagle never returned to its perch.

By 1991 only four mills remained in Dundee and at that point hardly anyone in the city once called Juteopolis earned their corn in the industry.

Tay Spinners, which was the last remaining jute-spinning factory in Europe, closed in 1998 with the loss of 80 jobs.

What became of the elusive bird?

Mark Watson from Historic Environment Scotland wrote a 1990 book on Dundee’s jute mills but said he has no idea what happened to the eagle.

“It was repositioned to look down Victoria Road in 1930 when Eagle Mill was formed there by Low and Bonar, which also then owned Dens Works, as the only new jute spinning mill built between the wars,” he said.

“It flew off in about 1980 when it became a kitchen shop.

“It had lasted well considering that it was wooden and had been exposed to the elements for 120-plus years.”

By 2016 inspectors were raising grave concerns about the condition of the Eagle Mills building and it was placed on Historic Environment Scotland’s At Risk register.

Site owner Eagle Mill Capital lodged £8 million plans to turn the B-listed building into 34 flats, a nursery, business units and vertical plant farm.

Other timber statuary over mills in Dundee included Minerva over Tay Works and James Watt at Upper Dens Mill, both lost in the 20th Century.

A and S Hendry’s Victoria Road finishing mill boasted an opulent marble staircase, Lawside Works an Italianate cupola, and Camperdown had polychrome brickwork and its fantastic chimney – even the Coffin Mill had a trendy flat-capped tower.

Bowbridge Camel was buried

The most grandiose was the exotic camel and rider modelled on Lawrence of Arabia which eventually topped the gate of Gilroy Brothers’ Bowbridge Works.

Different stories over the years started to emerge about what had happened to the statue after being dismantled from the top of the gates in 1955.

There was a suggestion it had actually been buried in the pool behind the joinery shop adjacent to Isla Street.

And it was variously reported to have been taken to Balgersho, near Coupar Angus, or to an estate in Inverness-shire, or even shipped to a jute mill in India.

There was even a poem written about the camel’s removal which suggested it had been buried under the pitch at Tannadice Park.

Jute Industries Ltd wanted to keep the camel but was advised it was very doubtful it would be possible to dismantle it sufficiently for re-erection.

The sculpture was dumped unceremoniously in a hole dug out for a new weighbridge.

The camel was in one piece when it went in, unlike the rider.

As for the Eagle’s eagle?

Might that mystery also one day be put to rest?

More like this:

Former cop reveals final resting place of iconic Bowbridge Camel

The fall of Juteopolis: How Dundee’s jute mills came tumbling down