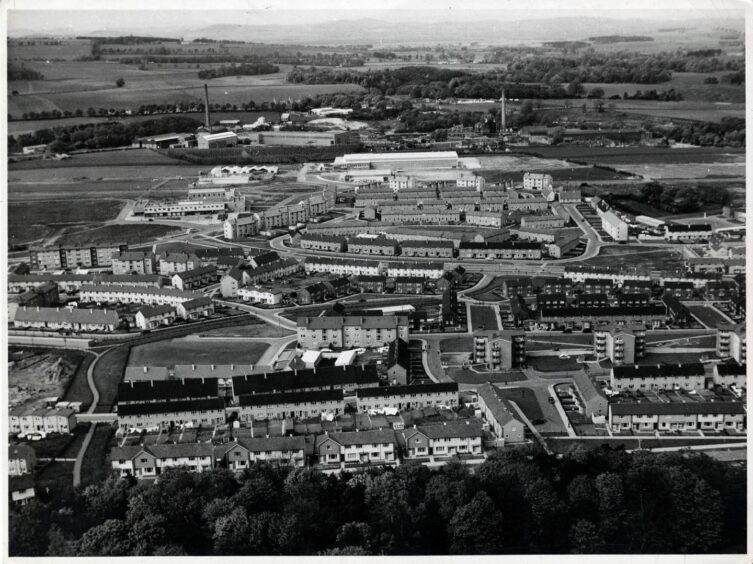

Glenrothes was hailed as the town of the future when it was planned in the 1940s as Scotland’s second post-war new town.

It was to house a new settlement of 32,000 to 35,000 miners who would be working at the newly established Rothes Colliery.

This was a largely unsuccessful colliery built on a grand scale that was perceived to be one of the costliest industrial mistakes in Scotland.

“The Rothes”, as it was known, was opened in 1957 but closed after just five years following concerns over flooding.

So how did the new town reinvent itself after the pit shut?

Dr Diane Waters has been investigating how the town has gone from strength to strength over the past six decades despite the pit’s closure.

Dr Waters is currently working on a research project with Edinburgh University about the history of Scotland’s new towns and takes up the story.

“A regional plan for Scotland was drawn up by Frank Mears in 1946,” she said.

“Mears was Scotland’s leading planning consultant from the 1930s to the early 1950s.

“He wanted a plan for housing for new and current miners near the Rothes Colliery.

“These miners needed a home, but not just any home; Mears wrote at the time that the miners wouldn’t be ‘living in the shadow of a pit’.

“They wanted to vastly improve housing conditions for the miners. They wanted a new town.

“Glenrothes was approved in 1948.

“In 1951 the plans were drawn up, and then a secondary ‘Master Plan’ was drawn up in 1952.”

The pioneer of new towns

“Glenrothes was different to the other Scottish new towns of the period.

“The other new towns were all about providing somewhere for the overspill from Glasgow to go.

“But Glenrothes was never intended to be one of these towns, and that impacted its layout.

“The town was to be split into individual boroughs, each with its own primary school and shopping centre.

“But that all had to change when the Rothes Colliery sunk.”

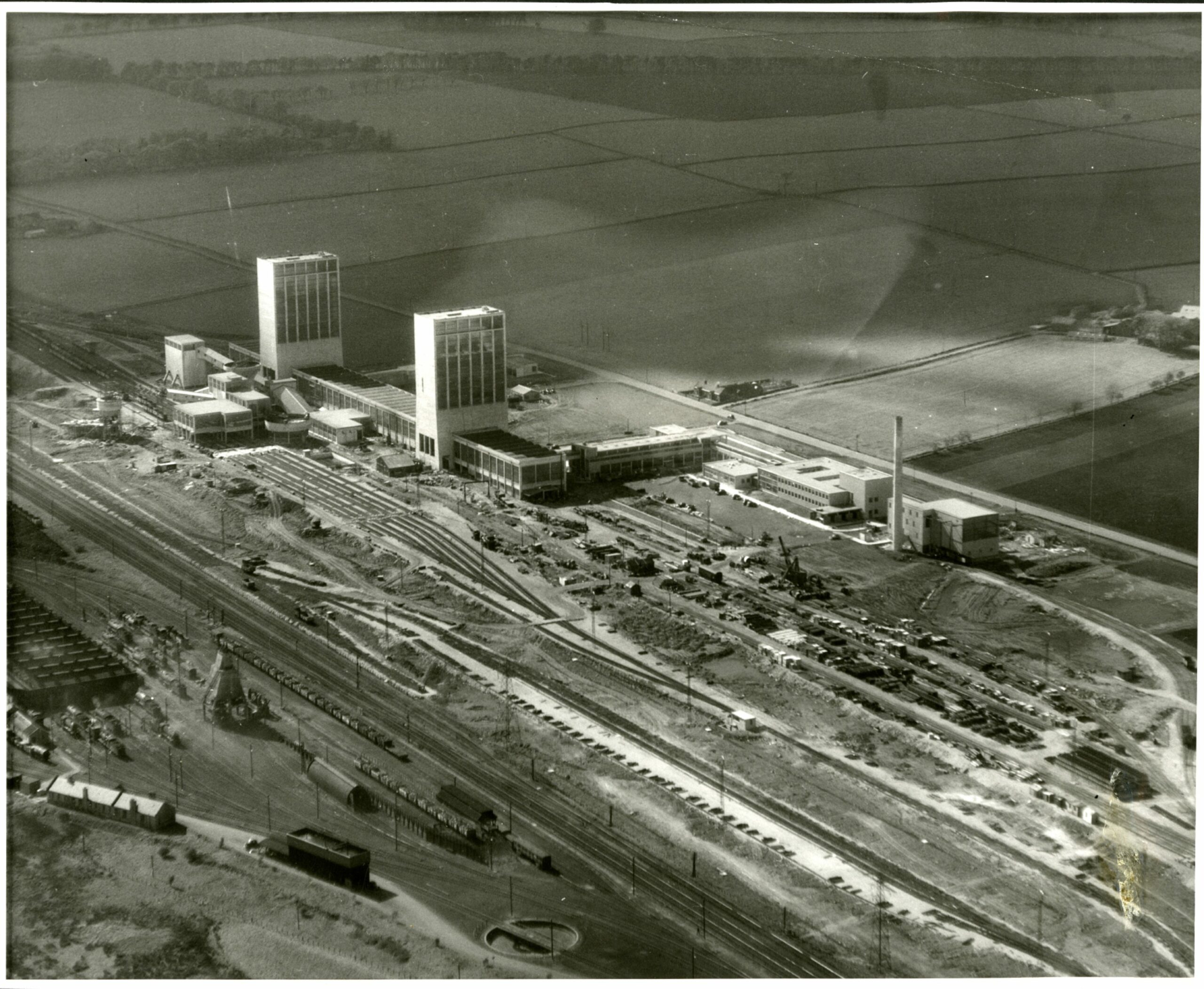

The Rothes Colliery, the new coal mine associated with the town’s development, was built near Thornton, an established village south of Glenrothes.

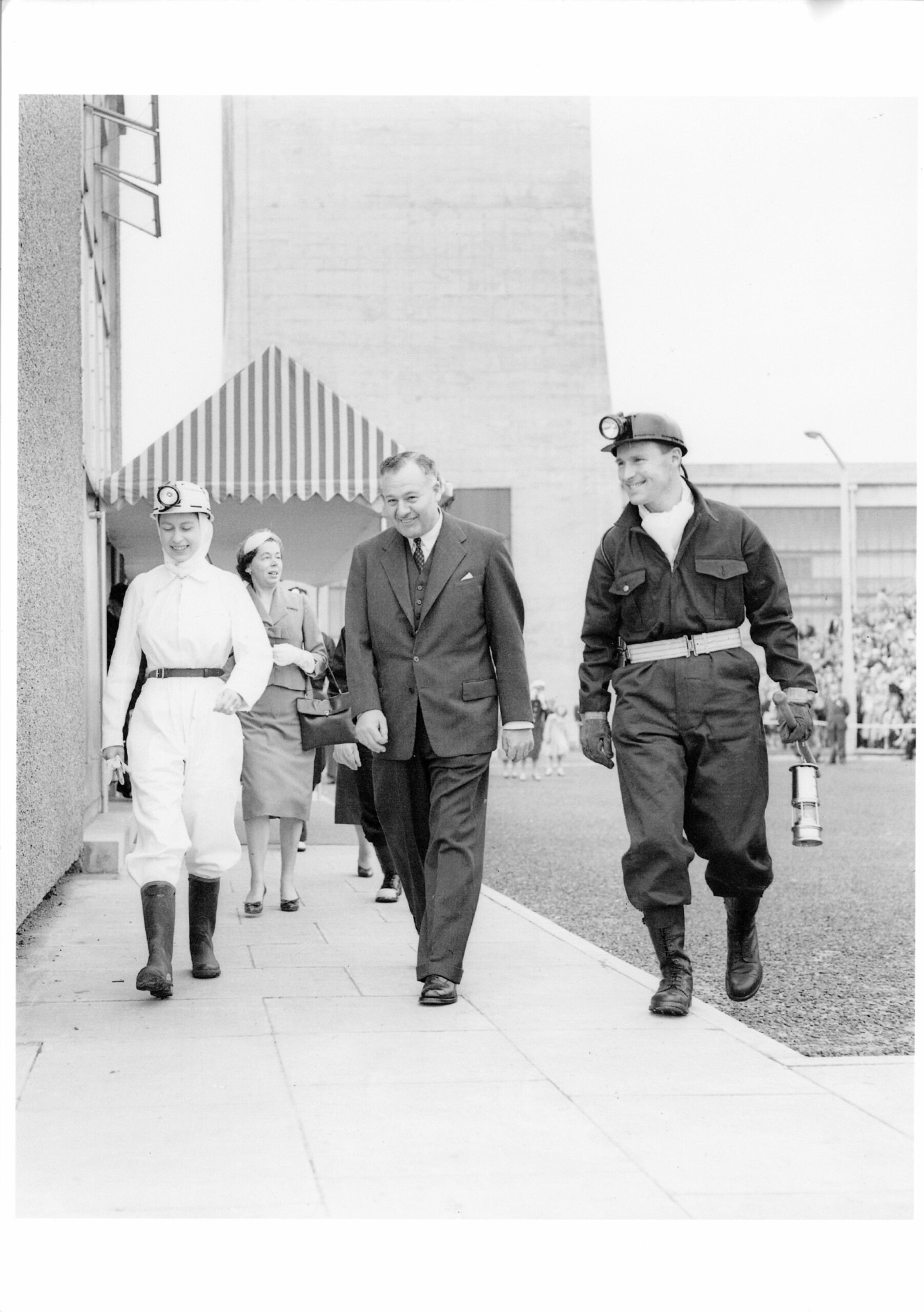

The mine was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 1957.

It was promoted as being a key driver in the economic regeneration of central Fife.

Rothes was planned to be one of the National Coal Board’s ‘Superpits’ and was projected to be producing coal until the 2070s!

However, the coal mine soon flooded and closed just eight years after it opened.

Miners who had worked in older deep pits in the area had warned against the development of the Rothes Pit for this very reason.

It was built in an unsuitable area and had several geological issues.

The coal mine’s closure almost resulted in further development of Glenrothes being stopped.

But Dr Waters says the reason Glenrothes has survived is because it has continued to reinvent itself over the years.

She said: “It all went wrong for Glenrothes when the Rothes Colliery flooded.

“The town had to rethink itself. What would it be now?

“The other new towns were still serving as overspill for Glasgow.

“So Glenrothes made a deal with the city, and plans are drawn up in 1969.”

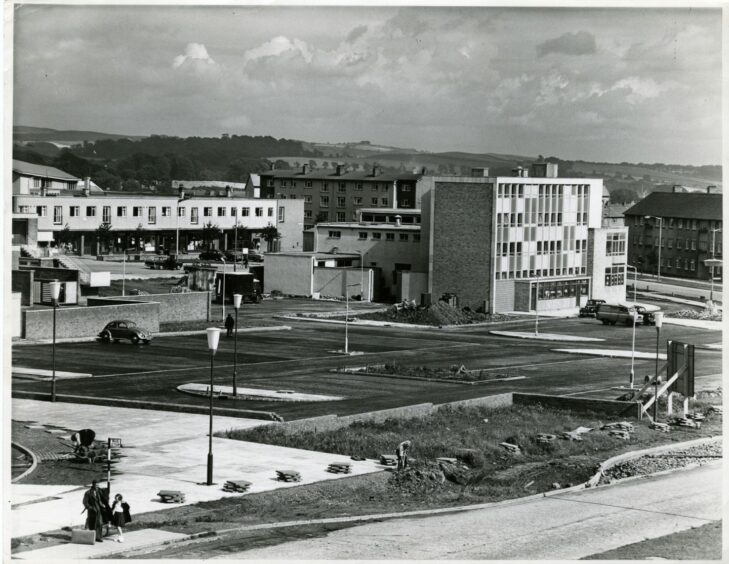

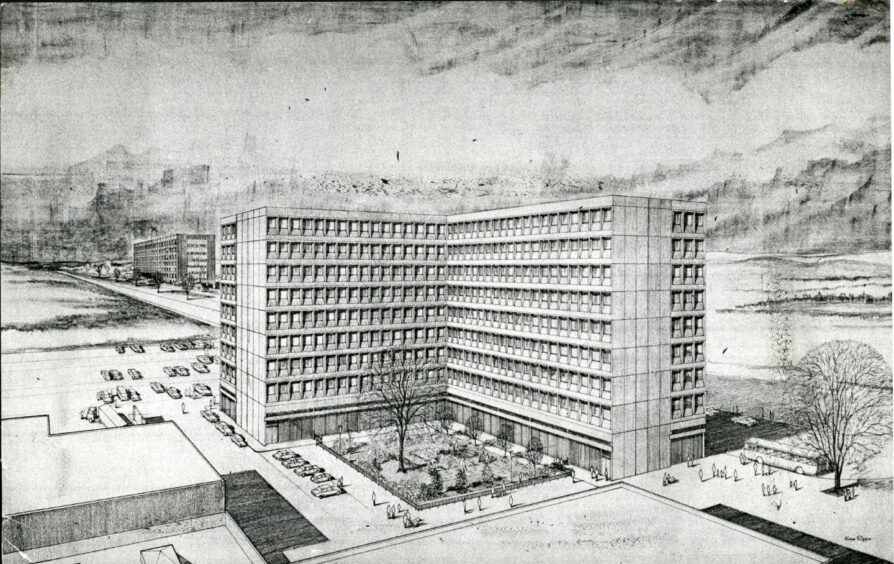

“This was a different period for architecture.

“There was a shift towards a dense, modernist type of housing, and a layout that kept people away from traffic.

“They built separate footpaths through the town away from the roads, which you can still see today.

“And this was also when they brought in the high rises.”

Raeburn Heights was built in 1968 by construction company Wimpey.

Originally there were to be four of the iconic tower blocks.

They would house business executives visiting from Glasgow as part of the town’s new deal with the western city.

But the people of Glenrothes were keen for more homes, and the planning company was forced to revise its plans.

The single tower block was simply extended and remodelled to provide more homes for the town.

“Raeburn Heights was commissioned by Glenrothes Development Corporation (GDC) who worked with Wimpey to build it,” said Dr Waters.

“Working with Wimpey was a totally different take to what was happening in other towns.

“Places like Kirkcaldy were building their tower blocks through local authorities and councils.

“Glenrothes using a development corporation was seen as a cut above the council housing.

“It was more aspirational.”

The GDC left a lasting legacy on the town by overseeing the development of 15,378 houses, industrial floorspace, office blocks, and shopping centres.

Since the demise of the GDC, Glenrothes continues to serve as Fife’s principal administrative centre and serves a wide area as a service, employment and retail centre.

But it wasn’t always such a positive hive of industry.

Dr Waters said: “My first interest in Glenrothes came from when I started working with the architects from the Glenrothes Redevelopment Corporation.

“I’m from a new town myself (Cumbernauld) and, like Cumbernauld, Glenrothes won the Carbuncle Award in 2010.

“My main aim when I started my research project was to counter the narrative of cultural, social, and community failure in Glenrothes.

“Everybody thinks the new towns are all the same.

“But Glenrothes is a good example of how diverse the design can be.”

The town has won awards for the “Best Kept Large Town” and the most “Clean, sustainable and beautiful community” in Scotland in the Beautiful Scotland competition.

It was also the winner in the “large town” category in the 2011 Royal Horticultural Society Britain in Bloom competition.

The town continued its horticultural success by achieving a second Gold award in the 2013 UK finals.

Dr Waters’ research will eventually be turned into a book about the Scottish new towns.

She added: “It’s such a positive story, how Glenrothes managed to turn itself around after the collapsing of the pit.

“It was once referred to as the street fighter of the Scottish new towns. It just kept fighting back.”

Now approaching its 75th anniversary, Glenrothes has proven it still has that fighting spirit today.

More like this:

The flats which changed the Kirkcaldy skyline forever

Dundee’s Ardler multis were a high-rise dream that turned to dust