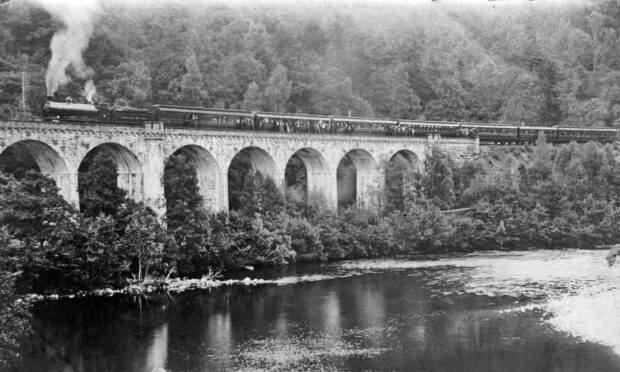

It’s a photograph that takes us back to long ago, but not so far away; an image of scores of passengers being allowed to get off a train on Killiecrankie Viaduct and stand at the edge of the parapet.

There were no health and safety regulations in the early years of the 20th Century, so if you wanted a good view of this magnificent setting, you simply left your seat, walked out of the door, clambered on to the pass and gazed down from the striking, castellated bridge.

It was an attractive option for many people and the seven-coach luxury excursion train, organised by the Polytechnic Touring Society, was one of many vehicles which transported thousands of passengers to Caledonia.

The trips were advertised as “A Week in Bonnie Scotland for Three Guineas” (around £280 in today’s money) and were carried out by locomotives from the Highland Railway’s ‘Castle’ class, which were introduced in 1900.

They proved an instant success, but if there was a glamour and romance to the journeys, they weren’t for the faint-hearted or physically fragile.

As Bernard Byrom, the author of Old Blair Atholl, Killiecrankie and Struan, declared: “The passengers were also expected to exercise by walking the 16 miles back to Dunkeld.

“But the clothes worn by the females in this staged publicity photograph would make even a mile of walking difficult.”

In short, they were a hardy bunch, but they revelled in their experiences.

And readers of this new work can enjoy a journey back to the pre-Beeching days when perjink little railway stations were at the heart of most communities.

The old postcards from that era testify to how much has changed during the last 100-150 years.

The shot above, of a southbound passenger train entering Killiecrankie, looks like Queen Victoria could have been on board.

When the station opened in 1865, it had minimal facilities, with just a platform for the single line, but expansion was in the air and this was a period when public use of the railways dramatically increased across Britain.

This was a grand attraction for visitors

Killiecrankie had enormous appeal for everybody from Charles Dickens to Arthur Conan Doyle – the pass was the sort of location that almost matched the setting for the famous clash between Holmes and Moriarty – and the railway authorities realised the potential for drawing in more customers.

Therefore, in 1896, a loop was created, and new platforms and a station building were constructed.

For the next 40 years, until people began to buy their own cars, these facilities were used by folk of all ages and backgrounds.

Sadly, the relish for trains ran out of steam after the Second World War, precipitating the now-notorious Beeching Cuts and the station was closed to passenger transport in 1965.

But the overbridge, which carries a minor road over to the west bank of the River Garry, remains to mark the site.

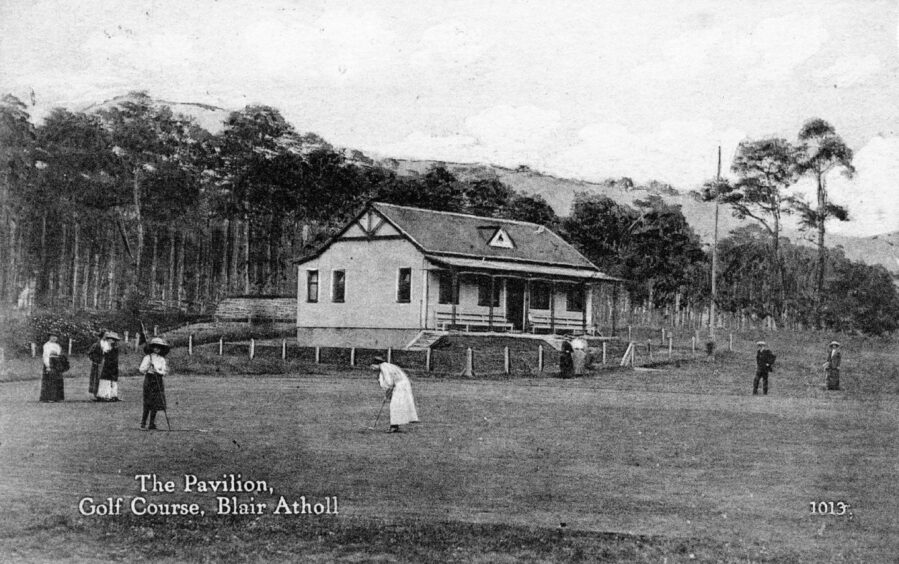

Golf is Scotland’s national sport, with amenities of every size, available to everybody and the trains conveyed many people to Blair Atholl’s smart little course, which was founded in 1896; another piece of vibrant Victoriana.

Mr Byrom explained: “Its nine-hole course was designed by the celebrated James Braid (who won the Open Championship five times and also designed the likes of Gleneagles and Dalmahoy).

“This picture shows Edwardian female golfers playing in front of the pavilion, which is actually the clubhouse.

“The course was converted to 18 holes after the First World War, but it reverted to nine during the Second.

“Nowadays, it is a nine-hole, par 35 course and going round twice gives a par 70 course of 5,780 yards in length.”

At least, it has managed to survive and thrive. Many of the railway facilities and routes were not so fortunate in the 1960s and 1970s.

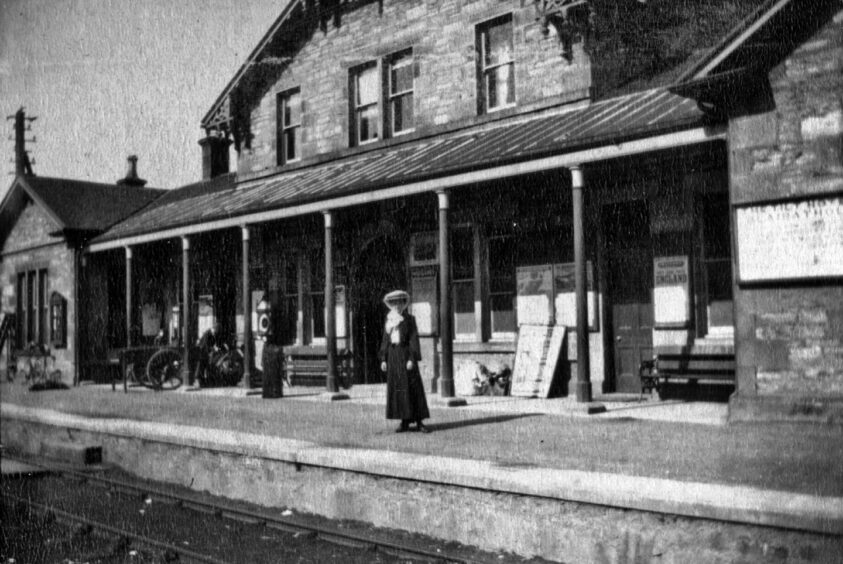

Thankfully, for those who live in the area, Blair Atholl was not one of the axed services and the station, 35 miles north of Perth, can look forward to celebrating its 160th anniversary next year.

It opened on September 9 1863 as part of the Inverness & Perth Junction Railway and, for the first 30 years, was named “Blair Athole”, until common sense prevailed and the title was amended.

However, it was honoured with a distinguished visitor in its very first week.

Mr Byrom said: “One of the first users was Queen Victoria, who arrived in a special royal train, only six days after the line’s opening, on a visit to Blair Castle, to see her long-standing friend George Murray, 6th Duke of Atholl, who was dying of cancer.

“The present B-listed station dates from 1869 and its design had to be approved by the 7th Duke of Atholl because it (the railway) serves Blair Castle.

“The canopy still survives today, but the near gable was demolished in the 1970s.

“And the station originally had a 770-yard-long passing loop, which was flanked by the two platforms, but this has since been extended northbound as double track as far as Dalwhinnie.”

Whatever the changes, it remains a jewel in the Highland crown – and the views provided by Mother Nature aren’t too shabby, either!

The same, however, could not be said of Struan station, which was built at the same time as Blair Atholl and also opened in 1863.

For decades, it served passengers’ needs and provided scenic journeys for tourists, but the latter were becoming ever scarcer by the 1960s and there was a sense of inevitability about what happened next.

As the author added: “It was a two-platform station just west of the River Garry, but the original, rather plain buildings were replaced after a fire in 1898 by the ones in the photograph (above).

“The station originally had two signal boxes, but these were replaced by a single box when the line was doubled in 1900.

“(However) it closed on May 3 1965, a victim of the Beeching cuts.”

Times had changed in so many of these once-flourishing transport routes.

Just to the south of the station was the Struan Inn, from where a coach service once ran to Kinloch Rannoch, about 12 miles to the south-west.

But once the public had access to cars and caravans, such old-fashioned and slow-moving ways of travelling from A to B were rendered redundant.

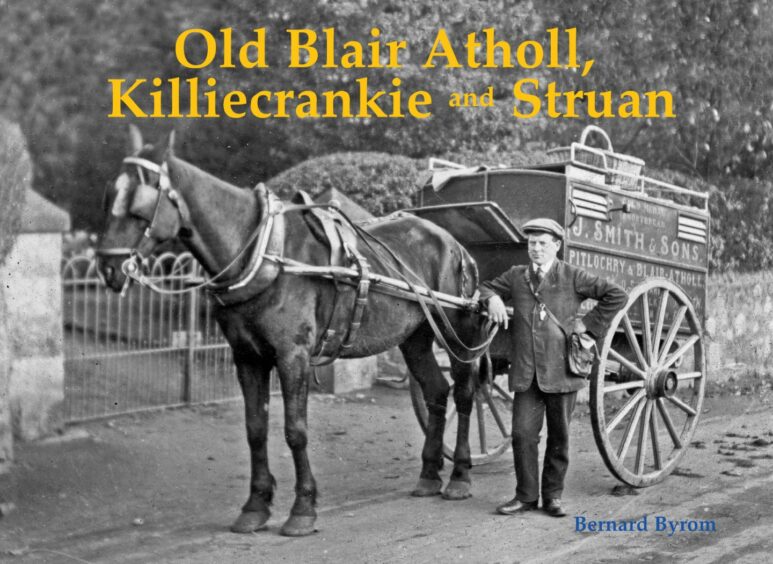

Mr Byrom’s work builds up a collective picture of how a way of life has disappeared gradually in Killiecrankie and elsewhere.

There’s one tranquil picture towards the end of the mountain of Beinn a’ Ghlo, whose summit at 3,671 feet classifies it as a Munro, north-east of Blair Atholl, which has the dream-like appearance of a distant, bygone age.

In the foreground is Loch Moraig, on which a young man poses on his rowing boat, moored off the loch side, as if he has all the time in the world. He, like all the other figures who appear in these images, is long gone now.

But the fascinating history and heritage of these communities lives on.

The book is available here.

More like this:

Going off the rails: The Tayside and Fife branch lines lost to the Beeching cuts

The end of the line for the Bervie to Montrose passenger train 70 years ago