John Buchan’s gentleman spy Richard Hannay outfoxed his pursuers at every turn and was the forerunner to James Bond 007.

Buchan was born in Perth in 1875 and it was his father’s profession as a Free Kirk minister that led the family to Kirkcaldy where he stayed until the age of 13.

Bond creator Ian Fleming is said to have been inspired by Buchan’s Hannay novels including his most famous book The Thirty-Nine Steps.

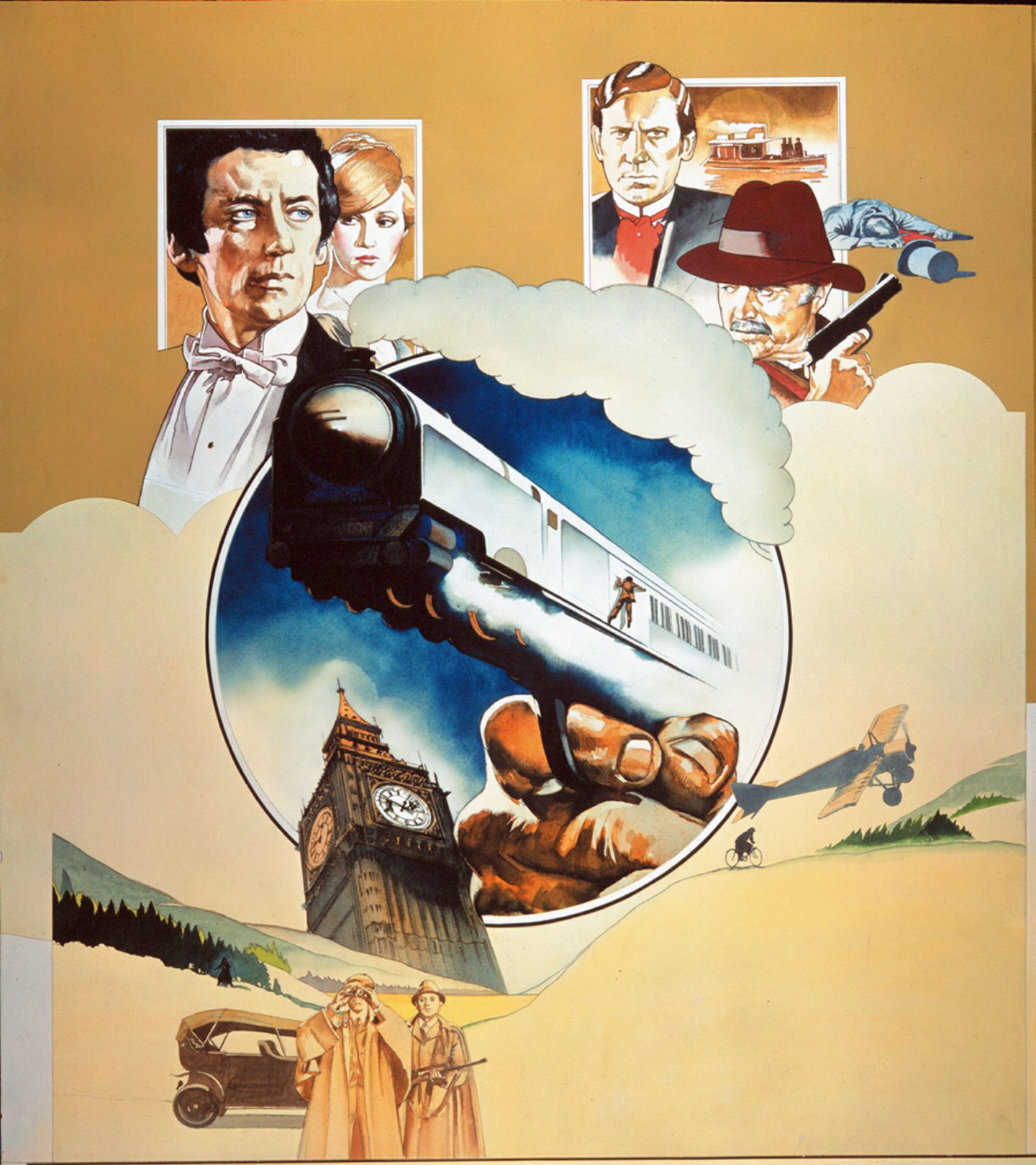

Buchan’s name became known across the world for the classic thriller which inspired numerous adaptations including the celebrated 1935 movie by Alfred Hitchcock.

Yet there was so much more to ‘JB’ who was a prolific writer of more than 100 books and 1,000 articles for newspapers and magazines before he died in 1940.

Buchan was also a scholar, antiquarian, colonial administrator, publisher, war correspondent, director of wartime propaganda, a Unionist MP, and, at the time of his death, the governor-general of Canada.

Buchan was intensely loyal to Scotland

Buchan’s author granddaughter Ursula is trying to keep his memory alive and has shed light on the thriller writer’s relatively humble beginnings in Kirkcaldy.

Ursula, who lives in Peterborough, walked The Thirty-Nine Steps to see where he spent his childhood and said Buchan was always intensely loyal to Scotland.

“As you know, he was born at 20 York Place in Perth on August 26 1875 but he left Perth as a baby, only about three months old, when his father, minister of the John Knox Free Kirk in Perth, was called to a church in Pathhead on the Fife coast,” she said.

“John attended the Burgh School, later renamed Kirkcaldy High School, from 11, and the family stayed there until John’s father was called to Glasgow when John was 13.

“So JB’s childhood was spent in the Kingdom of Fife, and it was a very happy one, recalled in two of his novels, Prester John and The Free Fishers.

“The manse in Pathhead was in Smeaton Road, close to Nairn’s linoleum factory, and across a byway from a coal mine, bleaching works and rope walk.

“As for Perth, there is a plaque on 20 York Place.

“I know that he was very proud of being a Scot, and he took pride from having made his way in the world, without privilege, trusting to his rigorous but happy Scottish childhood and youth.”

He was 13 when his father was called to a church in the Gorbals.

Buchan stayed in Glasgow until the age of 20 before successfully gaining a scholarship at Oxford University and he never lived north of the border again.

A trio of books published during the First World War cemented his reputation as a thriller writer and first among them was The Thirty-Nine Steps in 1915.

“I don’t think it’s his best novel, although it is very good, and much better written and more intelligent than a lot of the comparable thriller fiction at the time,” said Ursula.

“It was written very quickly, at the beginning of the Great War, and it was an immediate critical and commercial success, probably because it appealed to both civilian and service personnel alike. Men in the trenches are known to have particularly enjoyed it because it was very short, pithy, escapist, and it concerned one man desperately trying to save their country’s defence secrets. You can see why all that would appeal to them.

“The Thirty-Nine Steps still appears in lists of the 100 Best Novels.”

The movie was better than the book!

Buchan sold the film rights for £800 and the Master of Suspense Hitchcock used the ‘man on the run’ theme to create his first masterpiece in 1935.

“John perfectly understood the power of film, which is why he told the head of Gaumont-British, who made the movie, that it was much better than the book!

“No author had apparently ever said that to him before, but it shows John’s modesty, sense of humour and appreciation of what film could do.

“We shouldn’t forget the other two film versions, one in the 1950s starring Kenneth More as Hannay, and one in the late 1970s, starring Robert Powell. They are all most enjoyable and worth seeing, and they come round on the television quite often.”

But it was being granted the Freedom of Perth in 1933 at the City Hall which filled him with just as much pride as anything he achieved in his literary life.

“I think this has to do with the pride he took in being a Scot, which he never lost, even though he lived in England as an adult, until he went to Canada as Governor-General in 1935, and died there in 1940,” said Ursula.

“When in Canada, he always very much enjoyed enjoyed meeting those of Scottish descent who had settled in Canada, especially if they came from Perth, Kirkcaldy, Glasgow or Peeblesshire, which were the places he knew best.

“I have visited Perth, where I was amazed by the majesty of the River Tay, when the John Buchan Society met there some years ago, and also I have been to Pathhead and Kirkcaldy, to see where he spent his childhood. I have walked on the beach near Dysart, where he learned to swim and which he describes at the beginning of Prester John, listening to the oystercatchers piping, which was unforgettable.

“I have looked, in vain, for the manse in Smeaton Road and the kirk in St Clair Road, to get a sense of what it was like to grow up in that environment.

“I definitely understood my grandfather better, after I had visited Perth and Fife, and I had a chance to see the places that he had known in his formative years.”

When Buchan died in office in 1940, the editor of The Times newspaper said that he had never received so many letters about a public figure before.

He had just signed contracts for five books prior to his death and he was going to leave Canada that autumn and return to Oxfordshire to write.

“Very sadly, he died a number of years before I was born, which of course I regret hugely,” said Ursula.

“But he was only 64 when he died, which makes his achievements even more remarkable.

“I remember my grandmother, his widow, very well, for she lived on into her nineties.

“I wrote about going to visit her in the afterword of my biography of John Buchan.

“She was a substantial influence on me, for she very much encouraged me to read widely, and to study hard, and I took her advice seriously.”

Tears flowed down their cheeks

Ursula used family documents, papers and photographs to write an in-depth biography of her grandfather which landed in 2019 to excellent critical reviews.

She said: “Of course I am very proud of his legacy: he was a man who, without being born into wealth or high social status, made his way in the world entirely by his own hard work, high principles, and courage in the face of chronic long-term pain and illness (he was dogged by duodenal ulcers most of his adult life, which could not be cured in the days before antibiotics.)

“And thanks to his qualities, and the attractiveness of his writings, he is still widely read today.

“Everything he wrote is available in print or as a digital download, there is a thriving John Buchan Society, there is a fantastic museum, the John Buchan Story Museum, in the Chambers Institution in Peebles, and there is a John Buchan Way for walkers which stretches 11 miles from Broughton to Peebles.

“All of which I highly recommend!”

Buchan never forgot his Scottish roots during his lifetime.

“While I was writing the book, I came across many stories of his kindness and philanthropy that really touched me, but one sticks out: he was inspecting a dam in a very remote place in Canada and the whole area had turned out to hear him speak.

“He was told that there was a Scottish couple, who had emigrated from the Borders 40 years before, who had driven 100 miles to ’take a look at John Buchan’.

“He asked to meet them, and talked to them in their own Lowland Scots dialect, while the tears flowed down their cheeks.”

That was the magic of John Buchan.

More like this:

Sir Sean Connery, Clint Eastwood and the Fife golf movie that never was

John Buchan walked The Thirty-Nine Steps to the Freedom of Perth

Conversation