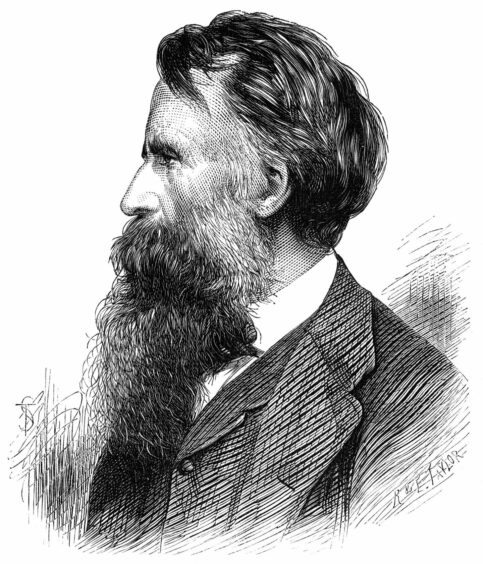

At the time, no one realised the significance of Patent No 10990.

The 23-year-old Stonehaven man who lodged it in 1845 turned out to be something of a visionary.

What he had invented would go on to revolutionise travel, making journeying on wheels a faster, quieter and far less bone-jarring experience than hitherto.

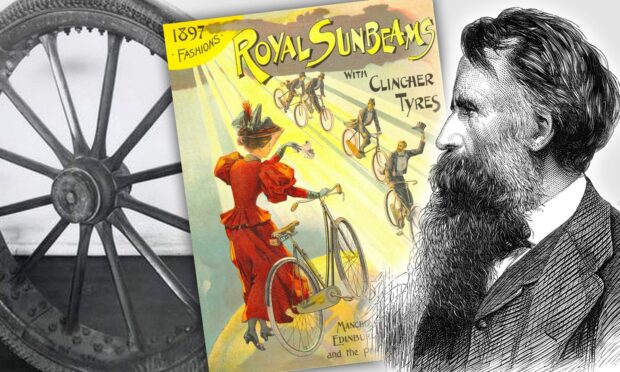

Robert William Thomson’s patent was for what would later become the pneumatic tyre, but he was way ahead of his time.

Bicycles were only just starting to appear on the streets, and motor cars were a little way off, but Thomson had worked something out.

He realised that a tyre filled with air considerably lessened the power needed to pull a carriage and made motion much easier.

His patent claimed that any wheeled item can be drawn or pushed with up to 60% less force and effort when air-filled tyres are attached, and can therefore travel faster.

Thomson proposed hollow leather tyres enclosing a rubberised fabric tube filled with air, and called them ‘aerial wheels’.

To prove their worth he ran a set of these wheels on a horse-drawn carriage for no less than 1,200 miles.

He also demonstrated them in Regent’s Park, London, in 1947 to show how they could reduce noise and improve comfort.

But the rubber for the inner tyres was so expensive that they couldn’t be made profitably and air-filled tyres were all but forgotten for the next 43 years.

Dunlop came much later

It wasn’t until 1888 that another Scottish inventor, veterinarian John Boyd Dunlop, devised his own design for a pneumatic tyre for bicycles, as a means of preventing the headaches suffered by his son when riding his bicycle on bumpy roads.

He was given his own patent for the improved pneumatic tyre, but two years later, this was rescinded due to its conflict with Thomson’s ‘aerial wheel’.

Undeterred, Dunlop continued his work on the pneumatic tyre, and by 1890 was mass-producing tyres for bicycles at a factory in Belfast.

The mind-blowing technological advances over 200 years have been unable to better Thomson’s concept.

Air-filled tyres still run in their millions over the planet’s roads.

Stonehaven born

Two hundred years ago today, on June 29 1822, Thomson was born in Stonehaven’s Market Square.

He was the eleventh of twelve children to a comfortably-off local woollen mill owner.

His destiny was originally to be the ministry, but Robert’s inability to master Latin put paid to that.

No one appears to have spotted his latent talent for invention at that point.

Apprenticeship in the States

Leaving school at 14, he headed to Charleston, South Carolina, where he was apprenticed to a merchant, but that can’t have been much to his liking as he returned home two years later.

He went to Edinburgh and applied himself to learning chemistry, electricity and astronomy with the help of an educated local weaver.

It was clear that Robert was practical.

His father gave him a workshop, and with it came the blossoming of Robert’s powers of invention.

He rebuilt his mother’s washing mangle so that the laundry could be passed through the rollers in either direction, cutting the labour down significantly.

He designed and built a ribbon saw; and made a working model of an elliptic rotary steam engine which he would go on to perfect in later life.

He was only 17 when he did all that, and it set him on his path for life as an engineer.

He served an engineering apprenticeship in Aberdeen and Dundee before joining a civil engineering company in Glasgow.

Invention saved lives in mines

After that, to Edinburgh were he worked for a firm of civil engineers and devised something which would reduce the loss of life in mines all over the world, a system for detonating demolition explosives by electricity.

His invention was approved by Michael Faraday and used on the Dover and South Eastern railway.

Thomson was only 19 at that point.

He went on to London and joined the South Eastern Railway Company where he worked under such prominent engineers as Sir William Cubitt and Robert Stephenson, son of pioneering railway engineer George Stephenson.

Thomson also set up a railway consultancy business around that time.

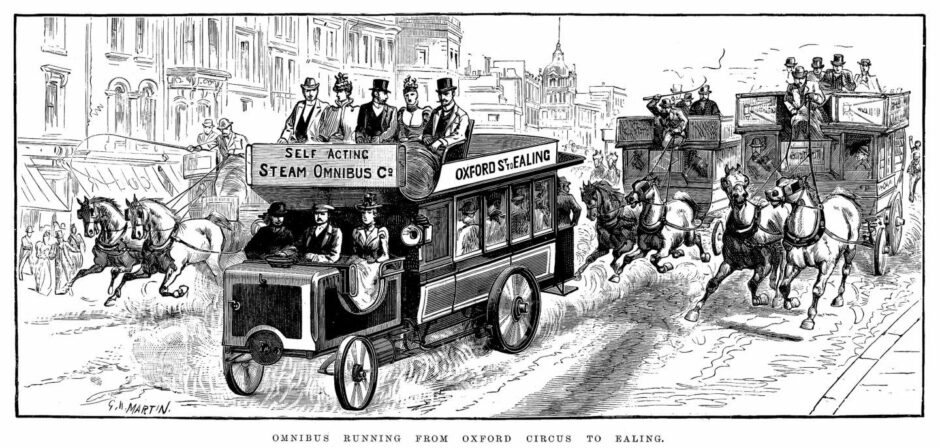

The list of his patents swelled to include the self-filling fountain pen, steam boilers, steam omnibuses, road steamers, elastic belts, seats and other supports or cushions.

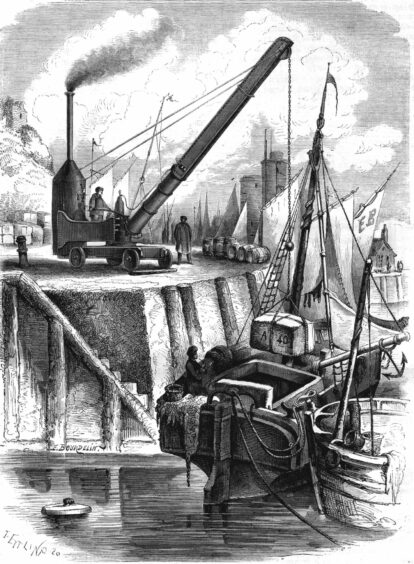

He’s also credited as originator of machinery for sugar manufacturing, the portable steam crane and hydraulic dry dock.

His inventions brought him wealth and the comfort of a huge townhouse at Moray Place in Edinburgh.

He was well-travelled too.

In 1852 he went to work for 10 years for an engineering firm in Java, where he designed his mobile steam crane.

There he met and married Clara Hertz, the daughter of a diamond merchant.

They had two sons and two daughters, one of whom would go on to marry Wind in the Willows author Kenneth Grahame.

Thomson died in Edinburgh in 1873, having packed a lot into his half-century on this earth.

He was inducted into the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame in 2020.

A bronze plaque commemorating the anniversary of Robert Thomson’s birth can now be found on a building to the south side of Stonehaven’s Market Square.

Each year in June, vintage vehicle owners and their machines gather in the town for a Sunday rally in honour of the great man.

More like this:

Postal pioneer: How Arbroath’s James Chalmers produced the forerunner to the Penny Black

Angus Peter Campbell: Great discoveries to be made on doorstep