“If you think it’s expensive to hire a professional to do a job, wait until you hire an amateur.”

Swashbuckling trouble-shooter Red Adair forged a legend in a 50-year career spent battling some 2,000 oil well fires in his trademark red overalls.

Adair risked life and limb again and again as he snuffed out searing blazes on runaway wells before a watershed moment as he tackled the Piper Alpha oil platform in 1988.

Adair admitted the North Sea operation made him realise he was too old and even to the day he died he said that it was the most difficult job of his career.

Life and times

Red Adair was born in the emerging oil capital of Houston, Texas, in 1915, and witnessed his first well fire at the age of six.

He took up the trade after serving in a bomb disposal unit during the Second World War where he learned about controlling fires and explosions.

After Adair served his time in the military, he returned home and was hired by Myron Kinley where he worked for 14 years helping to put out oil well fires.

In 1959 he resigned and founded his own company.

Adair shot to fame in 1962 when he led a daring team to put out a fire in the Sahara Desert which had raged for six months and became known as The Devil’s Lighter.

The flame was seen from orbit by John Glenn during the flight of Friendship 7 and the blowout and fire consumed enough gas to supply Paris for three months.

A character based on Adair was depicted by John Wayne in the 1968 film Hellfighters and Adair became the man to call when the task was beyond anyone else.

He put out several more notable fires in his career.

At the age of 73 Adair and his four-man team were charged with taming the flames after what would become known as The Night The Sea Caught Fire.

That was July 6 1988.

Piper Alpha

It all started with a pump that was missing a safety valve.

After the initial explosion, there were another three massive ones.

At its peak, the heat went up to 700 degrees on the 14,000t platform on Piper Alpha which was enough to melt the protective headgear worn by crew.

After the installation was engulfed by flames, 167 men were killed in the ensuing carnage and devastation on a night when everything that could go wrong did go wrong.

The devastated wellhead module, the only part of the platform to remain above the water, tilted at a precarious 45 degree angle, and was a smoke-filled maze of sharp, twisted, oil-covered, blistering metal.

Many of the 36 wells on Piper Alpha had been shut by down-hole safety valves, but that was unknown to the team at the time.

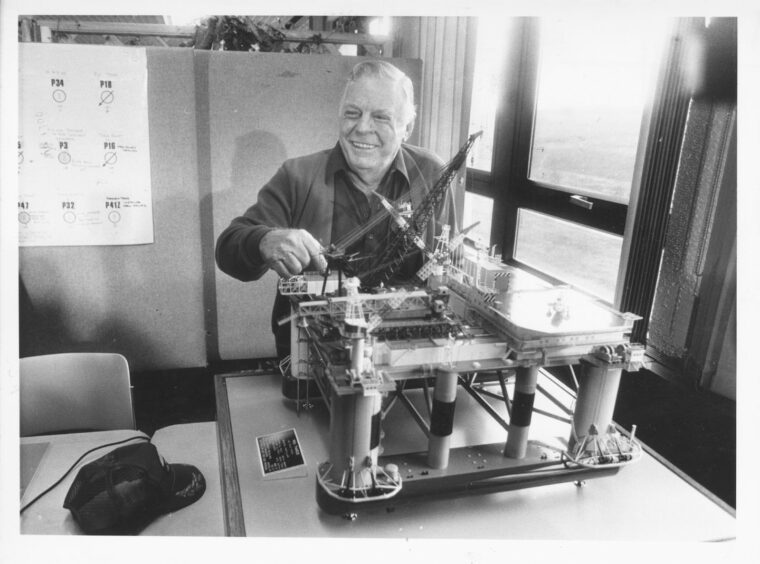

The job for Adair – flanked by trusted lieutenants Raymond Henry and Brian Krause – was to work out how many remained open, and plug them.

Though confident the wellhead module wouldn’t collapse, the team kept a careful record of everything they uncovered so that if the module did give way and fall into the North Sea, divers would be able to use the records to continue the job.

Adair’s team worked for 15 hours a day for three weeks, stopping only once, for three days, when the weather deteriorated to the point they could not battle on.

”The longest walk of your life” was how he described going up to see what was needed to cap the blowout, to study the structure of the rig.

”You know the dangers, you know the calculated risk,” he said.

“Like any job it is dangerous, but you know what the dangers are, you know how to cope.

“You take every safety precaution you can, and you are doing something for the good of everybody.”

But the legendary firefighter never actually stepped foot on the platform.

Despite having a fearless daredevil reputation, Adair had an even bigger reputation for health and safety when it came to the safety of his firefighters.

“I had to stand back and direct,” he said in the renowned 1989 biography, An American Hero: The Red Adair Story, which was written by Philip Singerman.

“They were younger and more agile.

“It was hell standing over there 150ft away trying to talk to them, attempting to tell them what to do, and they could not hear you because of the noise.”

With the flames briefly controlled, his lieutenants stuffed a sealing device into the well before pumping fluid to the bottom of the pipe, killing the well.

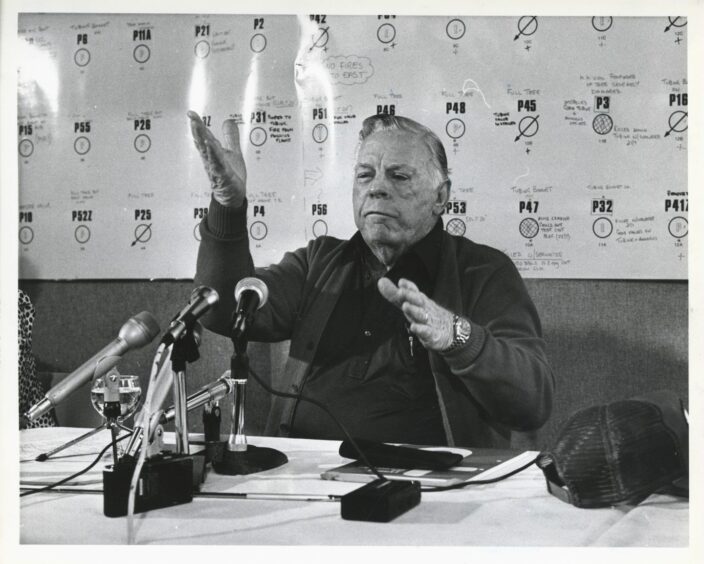

The remaining wells were sealed permanently with cement within two weeks, leaving Adair to hold a press conference where he described the wrecked rig as the worst he’d seen.

“I’ve never seen anything before like that in my life,” he said.

“It was as bad as you could get.

“I’m proud of my boys and the work they are doing out there.

“We are ahead of schedule, things have gone quite smoothly and nobody has even smashed a finger.”

He was still fighting fires at the age of 75

He said the massive loss of life on the platform also played on the minds of the team during the operation.

Adair said: “It was a terrible accident and there were so many lost – that’s still in your mind some place and it affects your work.”

The wellheads module was toppled into the sea in an operation using explosives in March 1989.

Still in action at the age of 75, Adair took part in extinguishing the oil well fires in Kuwait set by retreating Iraqi troops after the Gulf War in 1991.

“Retire? I don’t know what that word means,” he told reporters at the time.

“As long as a man is able to work and he’s productive out there and he feels good — keep at it.

“I’ve got too many of my friends that retired and went home and got on a rocking chair, and about a year and a half later, I’m always going to the cemetery.”

Adair finally did retire in 1993 and died in 2004, aged 89.

He remains a byword for bravery and daring.

More like this:

Rigging the game with Tabitha Lasley, the woman who broke into the world of North Sea oil workers

Charles Haffey sailed into the ‘sea of fire’ after Piper Alpha disaster in 1988