Liz McColgan had the world at her feet throughout 1991.

Hot on the heels of pummelling her rivals into submission during a stunning performance to win the 10,000m at the World Championships in Tokyo, the Dundee athlete was in the form of her life and was widely regarded as the favourite for gold at the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona.

Behind the scenes, Liz had been struggling with a virus which had pushed her way down the field at the World Cross-Country Championship, but confidence was still high that this indefatigable warrior would thrive when it mattered.

Indeed, Dundee City Council even sent the media an advisory notice prior to the 10,000m final in Spain, alerting us to plans for an open-top bus parade if she could repeat the heroics which had earned a string of accolades and led to her being crowned the BBC Sports Personality of the Year.

As it turned out, the bus stayed in the garage.

If the politicians and pundits had assumed Liz would enjoy a Spanish stroll in sweltering temperatures 30 years ago, she was typically honest in assessing the situation as she geared up for the showdown.

She was fully aware of the threat posed by a wonderfully gifted young Ethiopian, Derartu Tulu, the talented South African Elana Meyer, and the emergence of a group of rapid Chinese middle and long-distance runners.

To this day, rumours persist about the latter, given how several of the athletes trained by Ma Junren didn’t merely break, but shattered world records by 10, 20 and even 30 seconds with performances which came out of nowhere.

It was claimed “caterpillar juice” was the secret to their success.

Others wondered whether they might be part of a new breed of “hormone monsters”.

Liz said in the build-up to the final: “I know that this is going to be the hardest race of my life, because you’re up against the best girls in the world who have been training for the last four years to win a medal.

“I am going in with my eyes open and nobody will tell me it is going to be easy. It is very different in the Olympics.

“You get girls that you’ve never heard of before, and there will be a couple of really good Russian girls there.

“All they are doing is training specifically to win at the Olympics.

“It’s not just in my event but in all the events that people come out of the woodwork and you’re saying: ‘Jeez, where did they come from?’ and they’re winning.

“So you have to go into the Games aware of everyone in the field.”

At the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, Liz had put in what was described by most commentators – and certainly the likes of the BBC’s David Coleman – as a terrific display when she tackled the globe’s leading luminaries.

It led to her standing on the podium, but she “only” had a silver medal for company. And she was so disenchanted with the outcome that she chucked her medal in a drawer after returning home to Tayside.

She said: “Seoul really upset me, to the extent that I never even looked at my medal. It was just forgotten about.

“I felt that I had let everybody down.

“And that lasted until the Athens Olympics (in 2004) when Paula Radcliffe had her bad run (in the marathon).

“I remember she was sitting in the street and she was crying.

“Her distress made me realise that I had got a silver medal and I was complaining about it.

“So I went and got my medal – and it was actually the first time that even my daughter (Eilish McColgan) had seen it.”

When people study Liz’s career, they tend to focus on her boundless drive and determination and commitment to pursuing new challenges.

What’s often forgotten is that she was a young mother with an 18-month-old daughter, whom she had to leave behind when she ventured to Barcelona.

She said: “Going into a big race like this, it’s not the ideal place for Eilish, because we give Eilish 100% and I feel that if she came out here, there is no way she would be getting the attention that she needed.

“So she’s back at home getting spoiled by her grandparents. My dad keeps playing tapes over and over of the 1986 Commonwealth Games (where Liz struck 10,000m gold in Edinburgh), so she doesn’t forget us.

“But yes, I miss her tremendously and I phone home all the time just to make sure that she is all right. And I talk to her on the phone….”

Liz has never taken a backward step in her life, on or off the track.

But although she came into the race as the returning silver medallist and the reigning world champion in her realm, Barcelona turned into one of those occasions where not even this force of nature could bend destiny to her will.

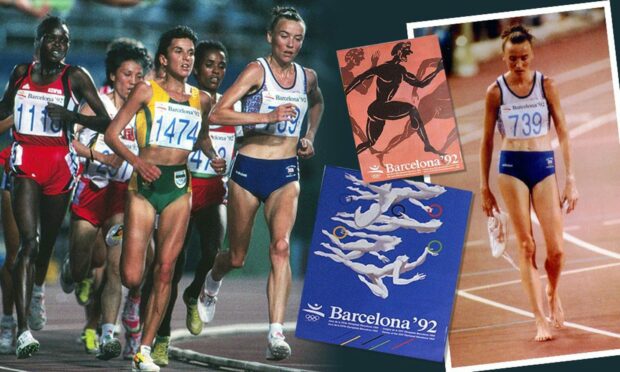

Straight from the gun, she took the lead and seized the initiative, just as she had done in unforgettable fashion in Tokyo 11 months earlier.

Yet, while she managed to leave many rivals trailing in her wake, South Africa’s Meyer, China’s Zhong Huandi, Kenya’s Hellen Kimaiyo and Ethiopia’s Derartu Tulu led a small pack that stayed ominously right behind the Scot.

Then suddenly, with nine laps to go, Meyer overtook her opponent and grabbed the lead.

It happened in the blink of an eye and the only one to chase her was Tulu, who made up the gap and followed in Meyer’s shadow.

That was how it continued until the bell but Tulu made her break in the closing stages with a devastating surge, as if to announce her arrival on the global stage and Meyer didn’t have the speed to prevent her running away.

It was a wonderful debut at the highest level and she finished clear of her rivals with Meyer in second and America’s Lynn Jennings in third place.

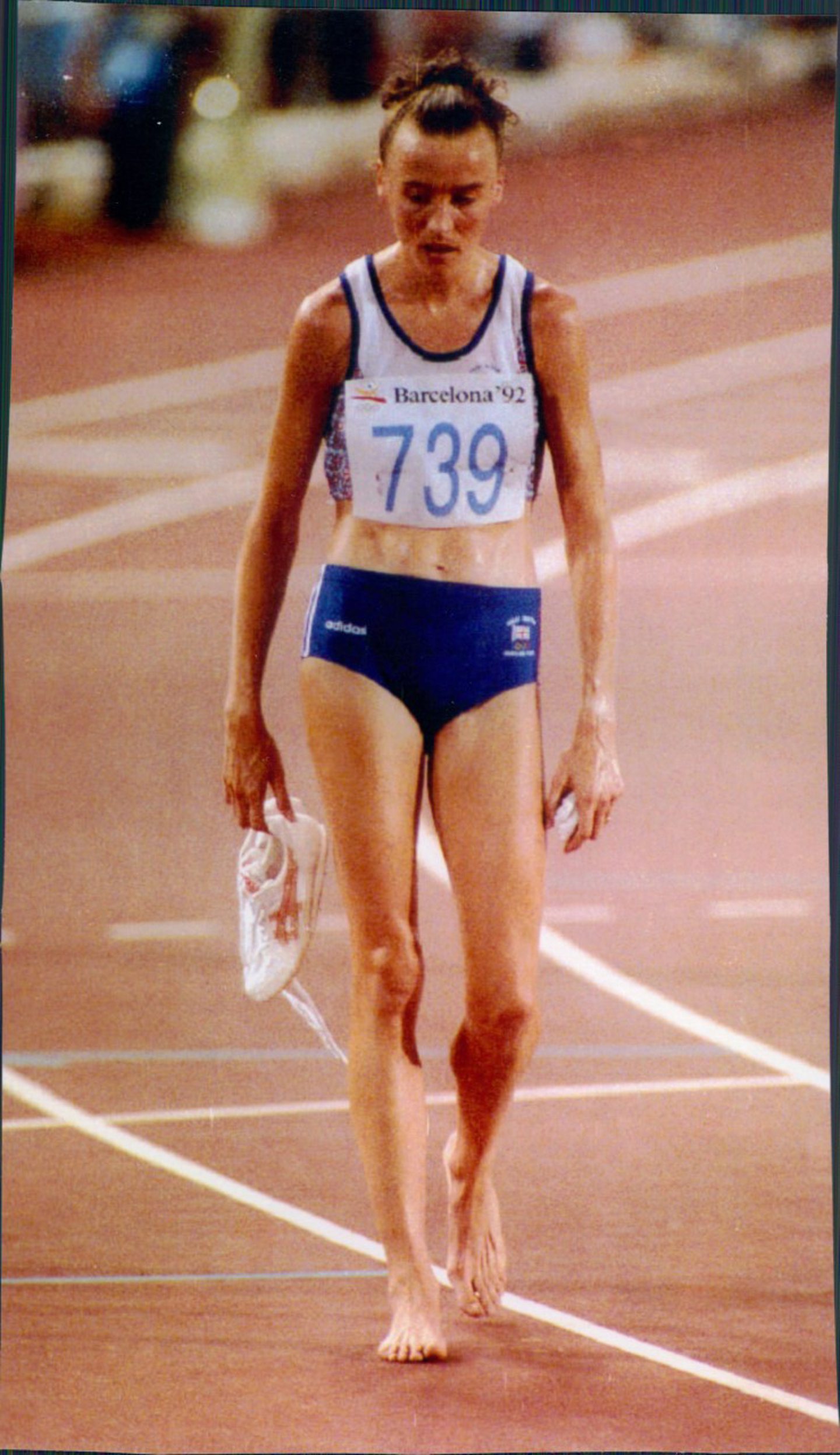

As for Liz, she ended fifth in a time of 31.26.11; which was almost 12 seconds slower than the 31.14.31 she had posted in destroying the field in Japan.

But, although understandably deflated, this wasn’t, as some observers prematurely predicted, the end of the road for her.

On the contrary, Liz moved up to the marathon and enjoyed many positive achievements in that event. The treadmill never stopped in the 1990s.

But, reflecting on Barcelona, she did admit that the viral infection which had plagued her for a significant spell had taken its toll in Spain.

She told The Courier in September, after the Olympics: “I’ve been suffering from it for probably about six months.

“I was very anaemic and it was stress-related, but I just ignored it at the time.

“Ever since Barcelona, I have been through treatment and different tests and I feel a lot better now.”

And she dismissed speculation that she had over-trained for the Games with the simple retort: “It wasn’t that. I just wasn’t healthy.”

Yet regardless of her problems, she competed all the same and kept toughing it out to the end, which is what you would expect from one of Scotland’s grittiest, most gallus sporting superstars.

More like this:

Liz McColgan: How training runs in the streets of Dundee led to Seoul silver and Tokyo triumph

The ecstasy and embarrassment of Liz McColgan and Robert Maxwell at the 1986 Commonwealth Games