Scots are used to dealing with extremes of weather, but the sight of snow ploughs on the A9 in 1976 sparked plenty of head-scratching.

Yet these vehicles were not carrying grit, but were loaded with sand in a bid to stop the tarmac melting on many road surfaces as the Highlands and the north-east basked in the hottest summer for decades.

Temperatures soared, not just for a few days, but for three months as Britain sweltered in temperatures which were more common on the Costa Brava.

In July, Aberdonians were forbidden from using hosepipes for watering gardens or washing cars and Grampian Region’s director of water services, Colin Mercer, issued a stark message that the situation has to be addressed.

A few days later, a notice appeared in Press and Journal, which read: “In order to conserve water supplies for essential trade and domestic use, it has become necessary to prohibit the use of water for certain other purposes.

“This applies to Banff and Buchan Division, EXCEPT for the ex burghs of Peterhead, Turriff, Banff and Aberchirder. It applies in (the whole of) Gordon Division, Kincardineshire/Deeside Division and Moray Division.”

There was no quick respite for anybody in Scotland, from farmers concerned about their crops to organisers of large-scale events who found themselves beset by spectators suffering from dehydration and sunstroke.

Several fires broke out on tinder-dry rough patches at The Open at Royal Birkdale and firefighters had to deal with extinguishing the flames even as golfers practiced for the prestigious event.

The conditions were even more problematic at Wimbledon, with thousands of tennis fans, including 400 in a single day, requiring treatment for sunstroke and similar ailments as the mercury reached 32 degrees for 15 consecutive days and the genuine prospect of drought affecting the nation intensified.

In mid-July, the Press and Journal reported on what was described as a “mounting crisis” with the Granite City facing its hottest summer since the 1860s. It reported: “Throughout the north and north east, the heatwave continued and the highest maximum temperature recorded by Glasgow Weather Centre was Lossiemouth with 86F (30 degrees).

“Fort William sweltered one degree behind, just in front of Aberdeen, Braemar and Dundee, and only the Western Isles was relatively cool at 63F (17 degrees). Forecasters are predicting ‘more of the same’ for several weeks.”

The demand in salad because of the balmy weather meant the price of tomatoes soared to 45p (the equivalent of approximately £3.15 per tomato in today’s currency).

But so many farmers’ fields were parched and arid that many crops failed, with the spectre of food shortages raised in parliament.

The fun didn’t last long for many in 1976 heatwave

At the outset, it was glorious, with the public flocking to the coast or their local parks and ice cream manufacturers and breweries cranked up production to cope with unprecedented demand from holiday-makers.

But soon enough, there was tragedy and distressing scenes as many Britons wilted under the wall of heat and too many found themselves in trouble when they ventured into lochs, rivers and other waterways.

Several people were killed on July 2 and 3 1976 after going swimming with friends and finding themselves out of their depths.

The Sunday Post reported on three deaths in separate drowning accidents, including a 63-year-old man in Glasgow and a 31-year-old man from Lochearnhead, with police in Perth urging residents not to take risks even if they considered themselves to be experienced in the water.

By the middle of August, the lack of rain and the paucity of water meant Britain was officially in the midst of a Great Drought – and the Government appointed Denis Howell to oversee the unprecedented emergency.

The Evening Express reported: “Mr Howell has been put in charge of the country’s dwindling water supplies and his installation as ‘water supremo’ was made following a crisis meeting of Ministers at Downing Street.

“A statement after the meeting – which was chaired by Mr Jim Callaghan – confirmed that Mr Howell would begin work on his new job immediately.

“The Prime Minister has called another top-level ministerial meeting for next week, underlining the major threat which is now being posed by what has been described as Britain’s worst drought for hundreds of years.”

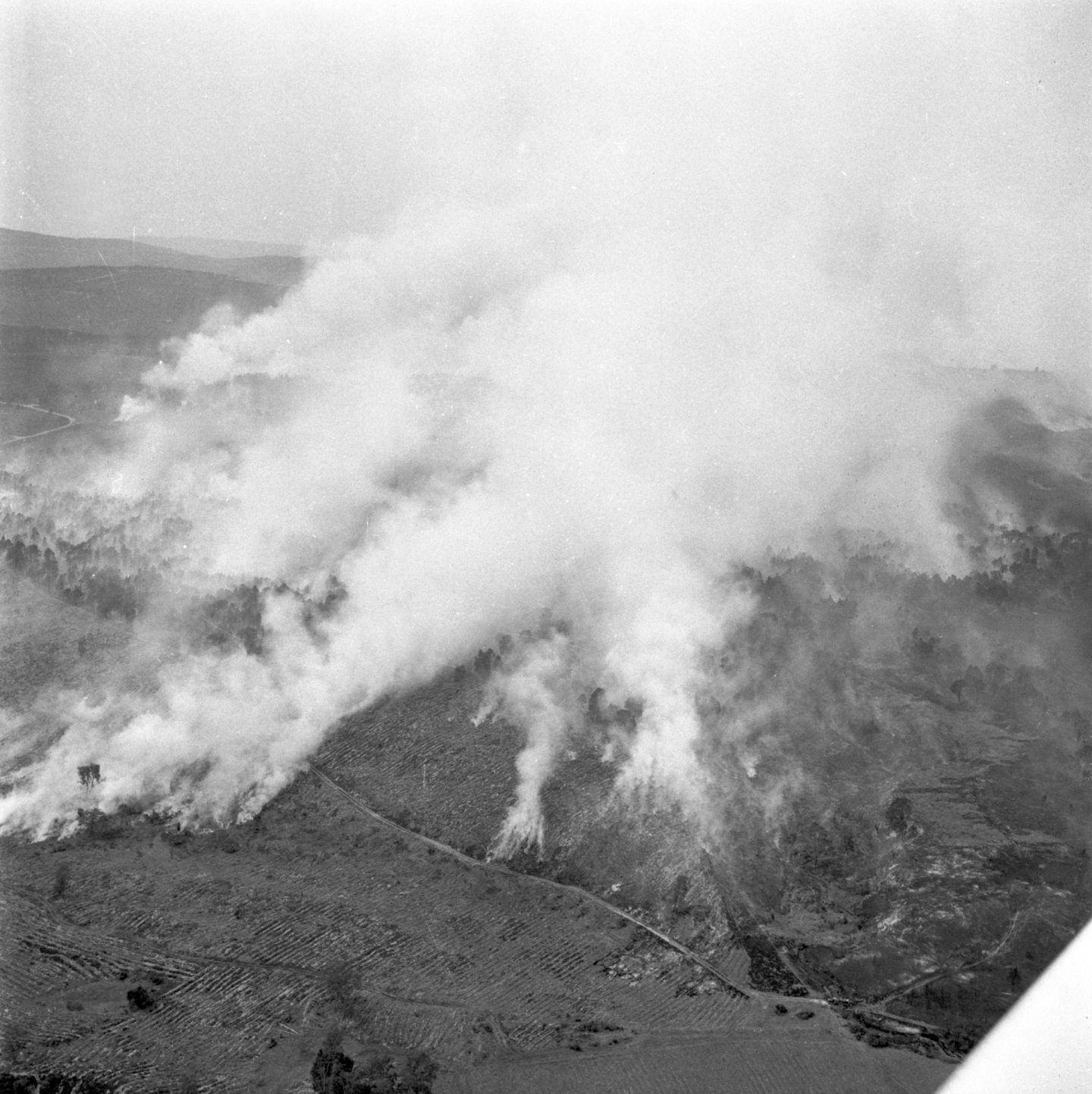

Even as the politicians were responding to the challenge, north-east firefighters were put under increasing pressure as hundreds of blazes erupted across the region on patches of gorse, moorland and in forests.

At Pitmurchie, between Torphins and Kincardine O’Neil, scores of emergency workers battled for hours to stop a conflagration spreading into villages.

But assistant divisional officer, Bob Wright, admitted to the Evening Express that he and his men had insufficient water to put out the fire.

In a remarkable interview, he said: “We are having to ferry water in units from a burn three miles away and take it across the fields. But we are not getting half the quantity of water which we really need.

“It’s an absolute oven in the centre with the fire burned right into the peat. So we will never ferry enough water to extinguish the fire completely.

“We will just have to work away and pray for rain.”

Finally the prayers were answered

As they ran short on short on ideas, British scientists even asked their counterparts in Australia about the process of “rain-making”.

It was believed by some officials that “seeding” the clouds with dry ice pellets, or “lining” them with silver dioxide might help to break the drought. It didn’t.

But at last, on the cusp of catastrophe, and as Britons were poised to celebrate the late August Bank Holiday, the heavens opened with a cataclysmic combination of thunder and lighting and torrential rain for several days.

It arrived after weeks of consternation in parliament and the media about how an island nation, surrounded by water, was running out of the stuff.

Howell, for a few weeks at least, was the hero who had restored normality and saved the nation. But his popularity didn’t last long. With the reservoirs parched, he was slated for insisting that the country would face rationing until December unless water consumption was cut by half.

But that was a one-off, wasn’t it? We’ll soon find out.

More like this:

Do you remember the 1982 snow storm that brought Tayside and Fife to a standstill?

Frozen in time: Braemar was colder than the South Pole in January 1982

Conversation