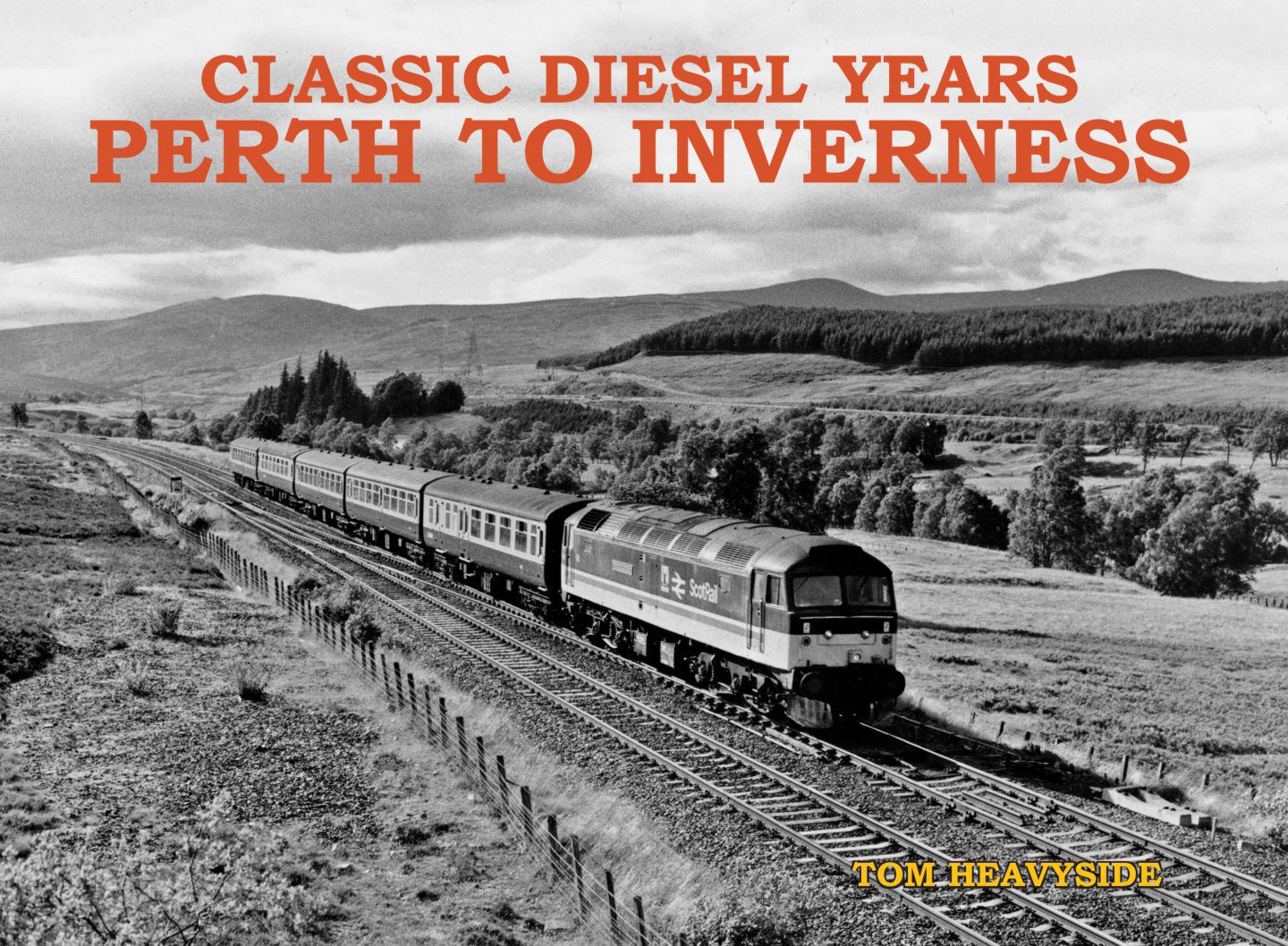

It’s more than 40 years since Tom Heavyside first ventured north of Perth by train and the Highlands have captivated him ever since.

As an avid railway enthusiast, he has spent decades rummaging through archives and piecing together the idiosyncratic story of the 118 miles which separate the fair city of Perth and the Highland capital of Inverness.

And even now, he waxes lyrical about the line, which threads northwards and which he regards as “one of the most scenic railway journeys in Britain”.

These pristine old vehicles come to life

Tom has methodically documented in a new book how the route was created, section by section, starting with the seven miles of track laid by the Scottish Midland Junction Railway, which opened to Forfar in August 1848.

But this is no dry account of how everything gradually came together, only for many of the stations which opened in the next century to be axed in the 1960s.

On the contrary, these myriad images of the wonderful old carriages which ferried countless passengers to the Highlands are wonderfully evocative – and will steer many people back to the days when they were Railway Children.

What emerges is a picture of a hectic golden age in Victorian times when different companies worked tirelessly to attract customers to their trains.

The Inverness & Perth Junction and the Inverness & Aberdeen Junction railways merged in February 1865 and became officially known as the Highland Railway just a few months later.

This was the catalyst for a rapid expansion and there was no shortage of enterprise or energy from those who pushed further north.

A bold move forward?

At that stage, no obstacles were too great that they couldn’t be negotiated. And the sheer hard work expended on the services reaped rich rewards.

A more direct route between Aviemore and Inverness, via Carrbridge, opened in November 1898 and there were so many scenic journeys available to customers even as we entered the 20th century.

Indeed, as Tom makes clear, the carriages went virtually everywhere and the images of the beautifully-tended stations takes us back to the days when nobody used cars and the train reigned supreme in the transport domain.

Eventually, as years passed, all the lines fell under the ownership of the London Midland & Scottish Railway, prior to nationalisation in 1948.

The latter policy was billed as a bold move forward. Yet it had ruinous consequences once the accountants began checking on passenger numbers.

As Tom said: “During the early years of British Rail, steam remained the sole form of motive power on the line north to Inverness, but its monopoly came under increasing threat following the publication of the BR Modernisation plan in 1955, which decreed that steam locomotives should be phased out and replaced by diesel or electric traction.

“Diesels first made their appearance beyond Perth in 1958 and, by the summer of 1962, had taken full command of services in the Northern Division. But, despite the investment, Highland communities anxiously awaited the findings of the Beeching Report into the future of the network.”

They had every reason to be apprehensive. For many of the regular passengers who relied on rail to travel to work, attend hospital visits and visit family and friends, life was about to become a lot more complicated.

Local services ‘doomed’

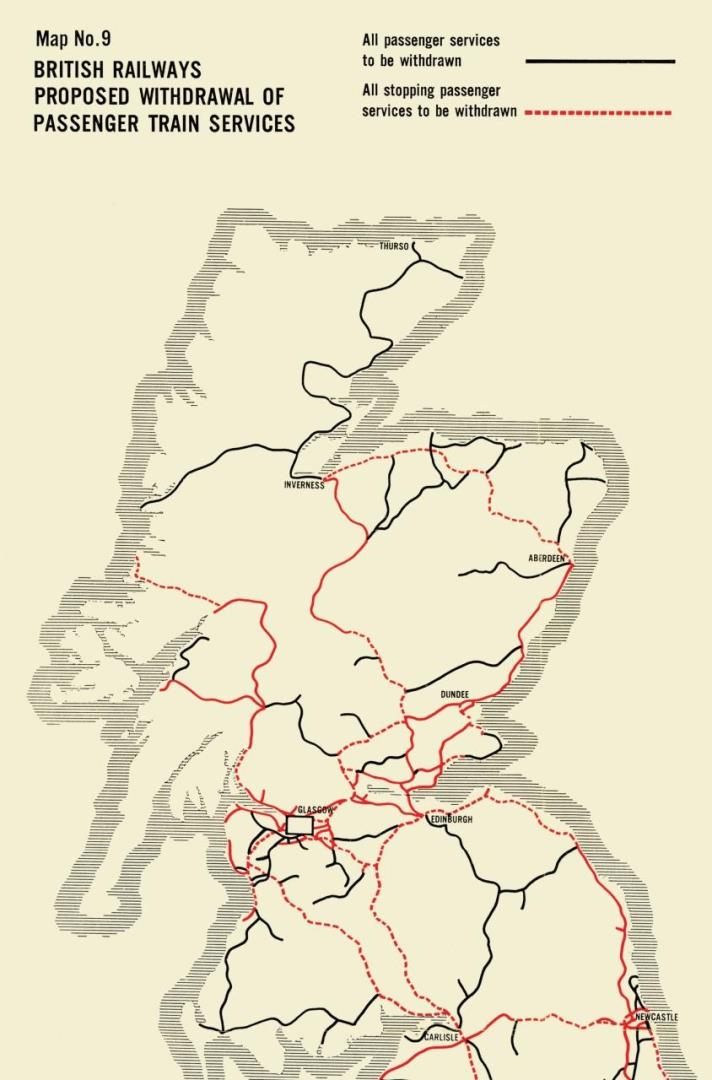

Tom explained: “Some feared that the difficult-to-operate and sparsely populated route between Perth and Inverness would be among those which were slated for closure, but to the relief of many – although sadly for those affected – it was only the local services that were doomed.

“As a result, the doors at 11 intermediate stations were locked for the last time in 1965, adding to the three that had already closed in the 1950s.

“Further economies resulted from the closure of some signal boxes and passing loops as well as the singling of the previously double-track 24-mile section between Blair Atholl and Dalwhinnie in July 1966.

“The four miles between Daviot and Culloden Moor were also singled in March 1968, although the double track north of Blair Atholl to Dalwhinnie was restored (and greeted positively by the public) early in 1978.”

Tom is quick to credit the endeavours of the heritage Strathspey Railway, an organisation “which keeps alive the spirit of past transport eras, both steam and diesel, throughout the Highlands”.

Yet, understandably, there’s an elegiac feel to Classic Diesel Years: Perth to Inverness, which is hardly helped by the current problems with services in many parts of Scotland and the attitude of those who regard new railway investment as a waste of money.

Journey back to past

If anything, Tom believes the opposite and he has highlighted the delighted expressions on the faces of the audience, young and old, male and female, at the sight of a McIntosh ‘812’ class loco, positively sparkling in the rain as it pulls into Boat of Garten station – one of the lovingly preserved places in the north, where it feels as if you are taking a journey back to the past.

There’s a sense of tristesse in these pages over the impact of the Beeching Report, which swept away virtually every Scottish branch line in the 1960s.

Conventional wisdom at the time viewed the losses as regrettable, yet inevitable, in an era of growing affluence – and the rising appeal of foreign package tours – allied to rising car ownership across the country.

But the report ignored the scope for sensible economies which could have allowed a significant number of axed routes to not only survive, but prosper.

However, for as long as Tom Heavyside and his fellow aficionados are fighting to restore heritage lines and re-open former routes, there’s still hope.

It’s a very different world from when he travelled to Inverness in June 1980, but he has lost none of his effervescence or enthusiasm for classic trains.

If you’re a fan, this book should be a treasure trove for your imagination.

Classic Diesel Years: Perth to Inverness is available from Stenlake Publishing.

Conversation