“Are you going to be our new mummy and daddy?” A small voice asked Jean and Johannes Surkamp at the front door of Ochil Tower School in November 1971.

The couple had been asked by Camphill community in Aberdeen to go on a fact-finding visit to see if the building would be suitable for a community school.

This first meeting with one of the children set off a chain of events that would change hundreds of young lives in the community.

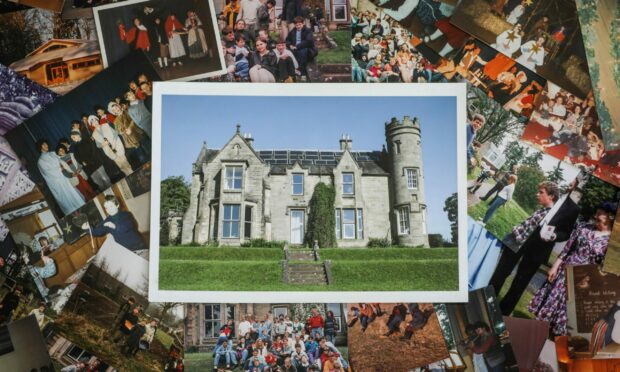

This year marks 50 years since Jean and Johannes took ownership of Ochil Tower School in Auchterarder.

Over those 50 years it became one of the most successful Camphill Scotland schools – a group of 11 schools which follow the teaching methods of philosopher Rudolf Steiner.

Jean and Johannes’ daughter, Rowan, has followed in her parents’ footsteps and continued to work at the school with her husband until the early 2000s.

On the 50th anniversary of her parents’ taking ownership, Rowan tells us just why the Ochil Tower school became such a pillar of the community.

Ochil Tower School

Rowan said: “My mum and dad were first sent to another school by the organisation, because the people that ran it were retiring.

“We’d only been there about four months when they got the call about Ochil Tower.

“They said, ‘there’s somebody asking for help in a rundown place in the backwaters of nowhere, in Scotland. Would you be interested in having a look?’

“And my parents were like, ‘Oh, my goodness, not another move.’

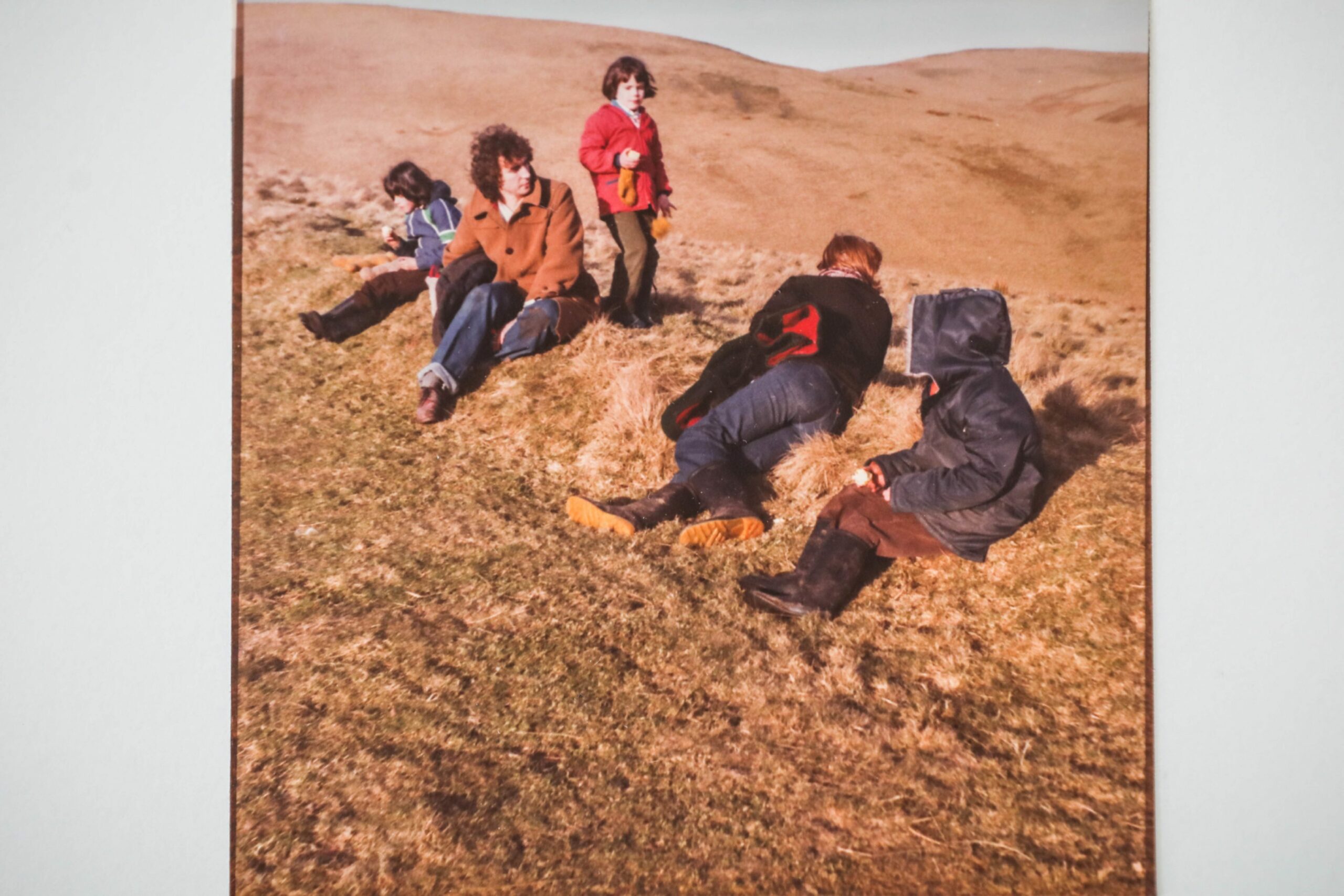

“We were a very young family. My sister and I were only two, and my big sister was only 4 or 5, and we’d only just settled.

“But admittedly they felt a bit like spare parts at the other place.

“So they said they’d go for the day and have a look.”

The couple arrived at the old building on a cold winter’s day in November 1971.

Rowan added: “They got down the drive, and they knocked on the door of this old castle-looking building.

“And the little girl opened the door, and she said, ‘Have you come to be my new mum and dad?'”

And they would be, of sorts, for both Jean and Johannes reportedly “felt led” to start working at Ochil Tower immediately.

The couple and their three young daughters arrived on January 3 1972 with all their worldly belongings in a van.

The rundown, draughty main building was to be their new home.

The 16 children who were already living in Ochil Tower were temporarily sent to other social work facilities around Scotland while the Main House was upgraded and decorated.

Jean and Johannes had three weeks to completely turn the place around.

Over 21 days, the central heating had to be overhauled, the walls had to be painted, curtains had to be put up, and beds needed to be made.

Despite all the odds, they got the work done and the children were able to return.

A handful of volunteers made the decision to stay and help look after the 16 children from difficult circumstances needing to be catered for.

New routines for everyone

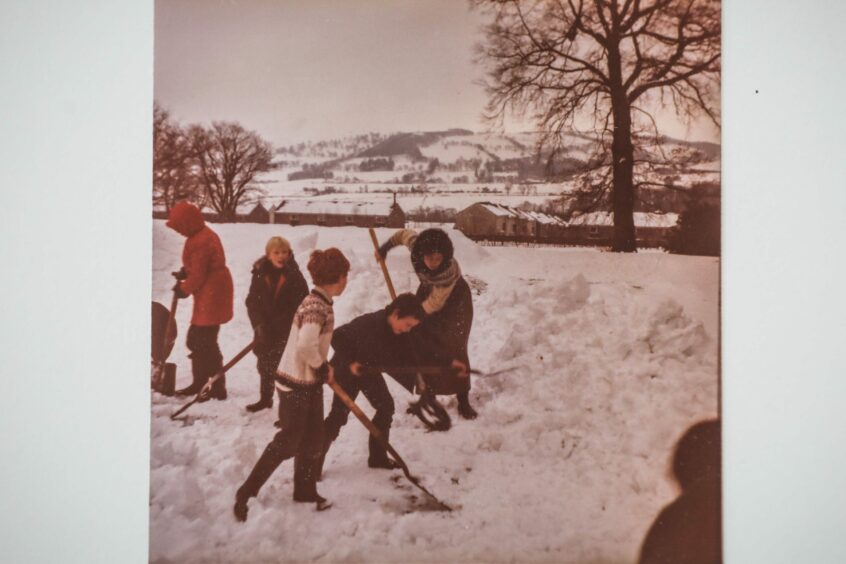

Rowan said: “And so life began.

“Daily routines and rules were put into place very quickly.

“A rota of daily chores was established, which everyone took part in.

“After supper, the children and co-workers would gather in the sitting room in front of the fire and listen to a story, before heading to their bedrooms for settling.

“It wasn’t like it is today, where the children each have their own rooms.

“In the early days, there could be as many as five children to a room.”

The establishing of routines and rules was a very important first step for the children of the school, who all came from difficult or disadvantaged backgrounds, or had additional support needs.

The gardens were soon turned into a fruitful food production source; animals were brought in for therapy, as well as for milk and meat in the form of sheep, goats, horses, and donkeys.

Rowan added: “Life was very difficult – but rewarding.

“Everyone worked as community and gave what they could in many forms – from carpentry, weaving, teaching, and gardening, to name but a few.”

But what else did they teach the kids?

Lesson time

Rowan remembers a proper lesson structure, and using storytelling to bring the knowledge to life.

She said: “We had Maths and English in the morning, and then ancient history.

“We loved Greek mythology, and the Romans.

“We did do the more normal First World War, Second World War, kind of stuff – it was always just done in a much more creative way.

“We’d teach them through stories, where we’d tell them the facts but in a really immersive kind of way.

“It was different to the state’s methods.

“Usually they were based solely on the facts – you just learned the dates and what happened on those dates.

“It was all very practical – every skill we taught them, we made sure they knew how to use in their everyday lives.”

Practical application

The children applied their maths skills in their pottery classes, when they were making pottery for each of their own dinner dishes.

English was turned into Shakespeare plays, used to entertain the community.

Rowan added: “It was all about understanding the world from a different place.

“In our pottery classes, it was as much about understanding where plates came from as it was about the maths skills or the creativity.

“We would make plates, bowls, spoons, and forks.

“It was very much a real teaching about being grateful for where things came from, and that if we looked after nature, then it would look after us.”

“A lot was centred around the festivals as well.

“We had Maypole dancing in the summer, and soul festivals, and we also had something called the Advent garden where each child would walk around a spiral of moss.

“They would make a candle first of all, in class, and the candle would be put in an apple.

“They would walk with their apple candle through the spiral to the centre, where there would be another candle, and then they would plant their light in the mossy garden garden.

“By the end of the afternoon, the room would be lit up with everybody’s little candle and they would be allowed to have that candle to take them to Christmas.

“The theme was just that they would have something there to help them through the dark days.”

The Sound of Music

“Everything was done with singing.

“We had all the old folk songs – it was a really musical time.

“I still remember harvesting all the fruits and vegetables, and prepping them on trestle tables, and listening to all the chatter and laughter and singing going on.

“We always had musical people around.

“The Scottish people would teach the Germans and the Danish our traditional Scottish songs, and then the Danish and the Germans would teach us their traditional songs.

“It was a real mix and celebration of all the different cultures.”

As the school grew, and more children came to know Ochil Tower as their home, how did they keep the place going?

Rowan said: “There was money, but nobody had wages.

“Everybody would communicate their needs, and nobody would be greedy.

“And nobody would see money as theirs.

“They would see that it was a need to buy essential things but, ultimately, we made most of what we needed.

“And we were grateful for the little that we had.”

Rowan began volunteering at the school when she was just 16.

After a short spell away from home where she completed her nursing training, she met husband Ian in the ’90s after she became fully qualified.

The two of them returned to help at the school in 1994.

After their wedding in 1995, Rowan stayed at Ochil Tower for another five years – while husband Ian stayed until 2018.

Johannes Surkamp

As for Rowan’s father, Johannes attended a Camphill school as a child and later went through the Rudolf Steiner teaching course.

He was able to convince the education authorities that he and his wife were capable of running a school.

His wife Jean, who had also attended the teaching course, was able to convince the social work department that living in the school in a home life environment was helping the children in a fundamental way.

Rowan said: “The children coming to Ochil Tower changed from being children in need of special care, to children with special needs.

“Eventually, as they grew up, they were able to live on their own in assisted housing.”

But once they left the building, that didn’t mean they had left the community that Jean and Johannes had formed.

Many of the volunteers and pupils from over the years kept in touch with the couple, including the young girl who greeted them on their first day.

Rowan said: “She came back and visited my dad.

“The fact that he’d had that kind of impact on someone – he knew that running the school was something he had to do.”

Johannes served at Ochil Tower for a total of 48 years.

Rowan added: “Dad just missed the 50th anniversary.

“He died in 2020.

“But he kept going until the very end – he did everything.

“He was the administrator, the accountant, the headmaster, the teacher, the gardener, the grounds person, the tree surgeon…”

Next steps

Apart from all his responsibilities at Ochil Tower, Johannes was asked by Camphill Aberdeen to find a training centre for the children to move on to after Ochil Tower.

Johannes helped in negotiations that assured the purchasing of Blair Drummond house.

After their time at Ochil Tower, the kids would be transported to the new premises at Blair Drummond to continue in their education.

Johannes later also found and negotiated the purchase of Corbenic in Trochry by Dunkeld, for the next stage of the process.

The kids would finally move into Corbenic as young adults, up to the age of 25.

These communities were funded by their local authorities, and later became part of a collective called Camphill Central Scotland Trust (CCST).

As for Rowan and her husband, they themselves left Ochil Tower shortly after Johannes passed away.

How have they been spending their time since?

Rowan said: “Our way of life is much the same.

“We’ve got a big garden full of vegetables and fruit, cucumbers and tomatoes…

“Some of that way of life, you do have to leave behind.

“But you make it your own, and take with you the parts that can fit with your lifestyle.

“We’ve managed to keep the parts of Ochil Tower with us that resonated.

“In some ways, it’ll always be a part of us.”

Conversation