They left for work 55 years ago and never came home.

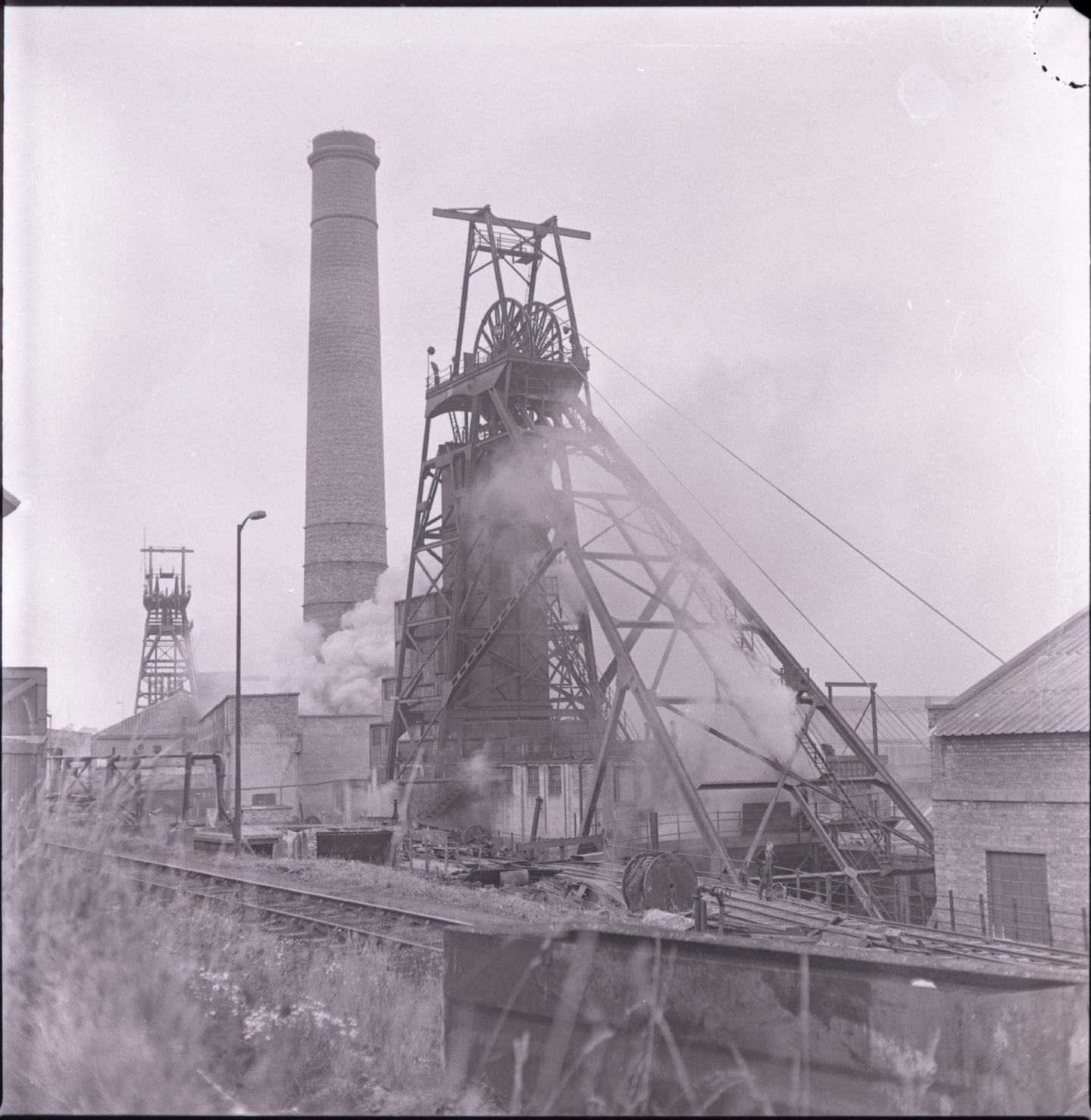

The nation united in grief following the pit disaster at Michael Colliery which marked the darkest day in Fife’s mining history.

A horrific fire at the colliery in East Wemyss claimed the lives of nine men.

Three of the bodies were never recovered.

It closed the mine for good, putting 2,000 people out of a job.

The pit, first sunk in 1892 and once one of the most productive in Scotland, was sealed by the National Coal Board, never to produce coal again.

The disaster tore the Wemyss community apart and left an indelible mark, still fresh in the memories of those who lost loved ones, friends and colleagues.

September 9 1967

Six hours earlier on September 8 1967, 311 men were underground, preparing to finish a long and gruelling shift.

Jimmy Drummond, a deputy in charge of safety for a group of miners, was alerted to the fire by phone at 3.45am on September 9 1967.

He ordered his own men to return to the surface, then returned himself to warn a group of miners that were working a part of the mine that couldn’t be reached by phone.

By this time, plumes of thick black smoke were rising from the colliery.

Telephone calls were made and the alarm was raised, triggering a mass evacuation.

Miners abandoned their equipment and used their free hands to grab each other’s hands, belts, whatever they could to form a chain and lead each other to safety.

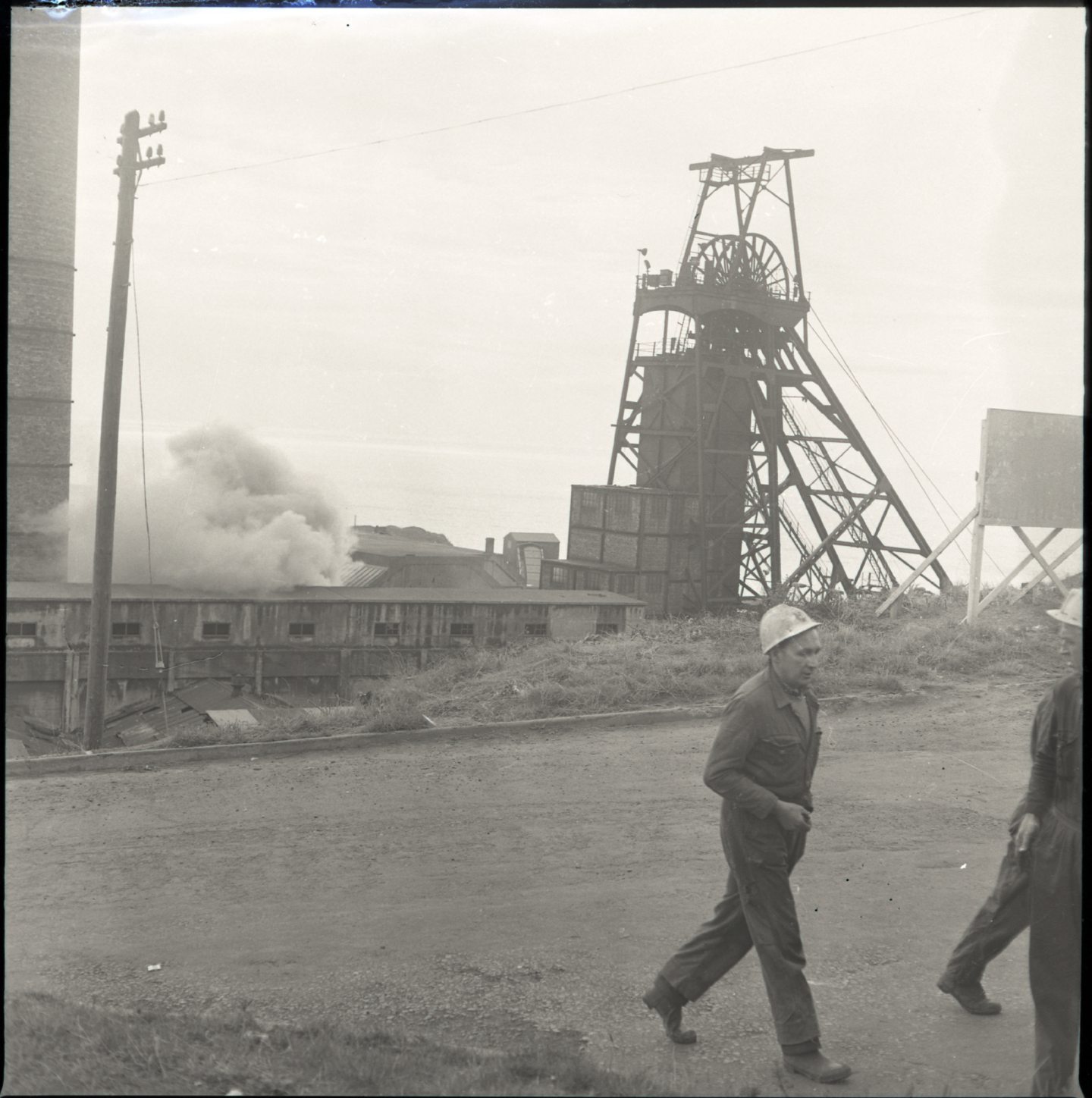

But not everyone was accounted for and so began a 36-hour rescue operation.

Rescuers including 20 teams from across Scotland and fellow miners risked their own lives trying to save those trapped.

In the midst of the sadness came tales of great heroism.

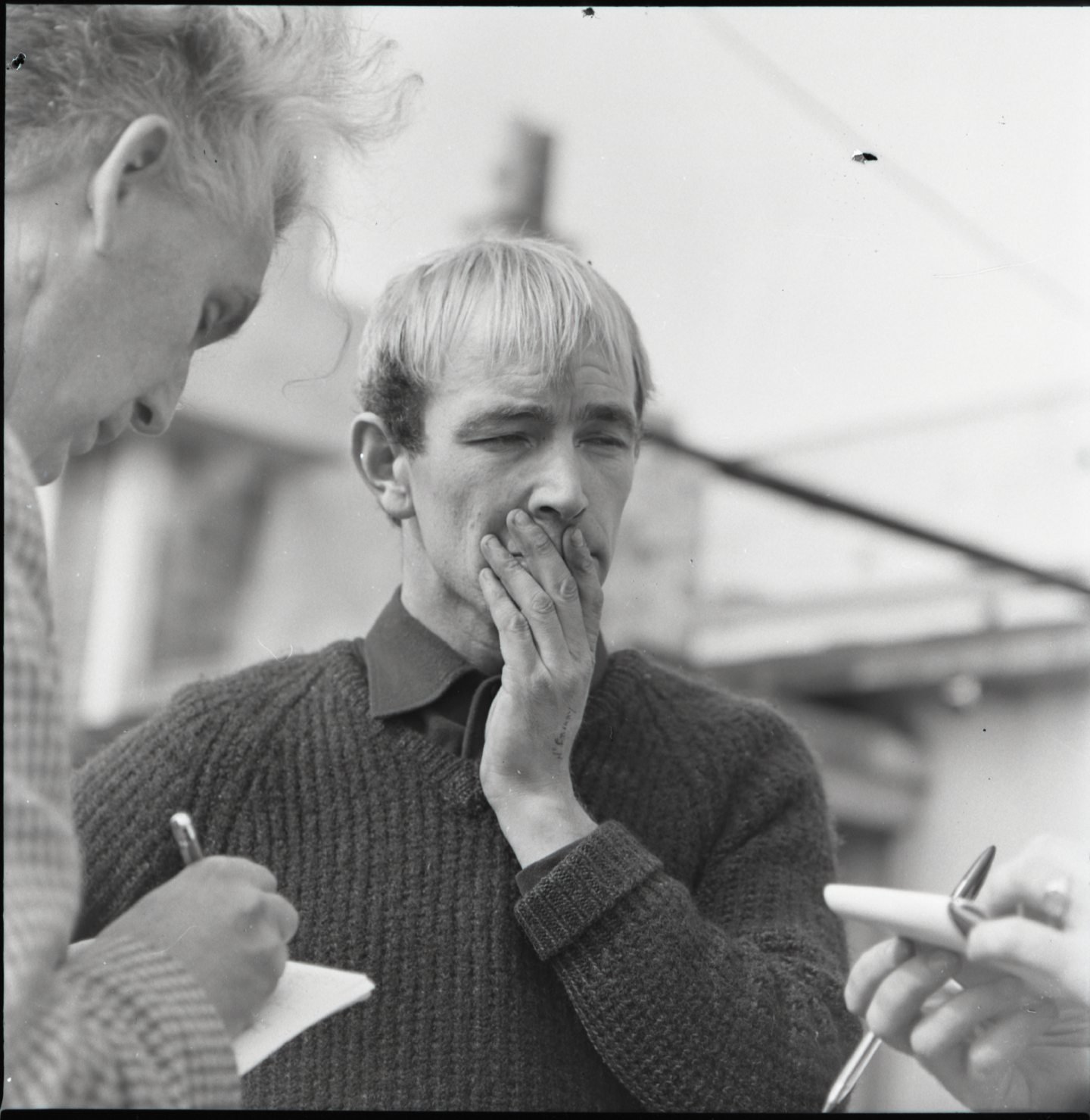

One man got back to the pit bath then realised his mate wasn’t there.

He walked back 500 yards without apparatus and brought him back on his back.

One worker said it was like looking into the gates of hell.

By 11am, six bodies had been recovered before a breakthrough at 2.30pm.

John McEneany and John McArthur were brought out alive.

They’d managed to shelter from the smoke.

With the chances of finding the last three becoming increasingly slight, efforts continued for another 24 hours until ending at 3pm on Sunday September 10.

Andrew Taylor, 43, received a posthumous award, the Edward Medal, after entering the smoke-filled tunnels to successfully rescue a man, never to emerge himself.

His body was never found and along with that of Hugh Gallacher, a 61-year-old pump man, and James McKay, a 59-year-old greaser, remains entombed under the ground.

The others killed by toxic fumes were Alexander Henderson, 41, Henry Morrison, 36, Johnston Smith, 60, James Tait, 41, and Andrew Thomson, 55.

Just 24 hours after the blaze broke out, Scottish National Coal Board chairman Ronald Parker announced that the pit would close temporarily.

The fire continued to burn in the pit for 19 days.

Extinguishing the flames was a slow process because the high percentage of carbon monoxide which was present put firefighters at risk of poisoning.

They were also at risk of explosions and fanning the flames.

A new fire broke out in the pit in the wake of the disaster which ignited a pocket of gas and caused a small explosion which injured four men.

An inquiry blamed the fire on the spontaneous heating of coal, which can result in combustion with only the tiniest draft of air.

In the weeks before the disaster two other fires resulting from “heatings” had occurred.

Rather than being bricked up or concreted over as was the previous practice, these had been treated with polyurethane foam.

This foam lining was said to have concealed the heating and created the black smoke which hampered the rescue.

Two lessons were learned from the Michael Disaster.

The use of polyurethane foam was banned in mines and from then on every miner was issued with emergency breathing equipment.

What became of the Michael Colliery?

The National Coal Board decided not to reopen the colliery in December 1967.

The first reason was that the cost of repairing the damage by fire and water and of carrying out work to make the pit profitable was, at that time roughly £5 million.

The second was that it would take about three years to bring up the output to what it had been before the pit closed.

The third was that the production from the pit was not essential to the Board’s operations, that the lost production could be made up from other sources from within Scotland.

There were 2,184 men employed when the pit was closed.

Of those, 1,019 transferred to other pits, 1,026 were made redundant or retired, 122 left the pit of their own accord, and 17 remained “on care and maintenance”.

In 1969 there was still debate in the House of Commons about the possibility of the abandoned pit reopening to tackle the level of unemployment in East Fife.

Fife West MP William Hamilton spoke to the Coal Board which said that the total amount of investment required to reopen the pit would now be about £8.5m.

The Coal Board said it would be possible to produce 960,000 tons of coal a year by 1972–73 with proceeds amounting to £4.7m.

The costs however would be £5.1m with a loss of £408,000.

Mr Hamilton said: “So the Board has calculated that there would be a loss both before and after the charging of interest. I make the point that this is the Board’s case for not reopening on the financial estimates which it has made.

“The Board estimates that the total production in Scotland by 1972–73, without the Michael, would be roughly 13 million tons a year, and that demand at that time would also be roughly 13 million tons a year.

“In addition, there would be strategic stocks of coal at Longannet power station, which is not due to come into full operation until 1972–73, and there would be similar stocks at other stations and, therefore, adequate supplies to meet the market without the Michael.

“The conclusion seems to be that the reopening of the Michael offers no financial return, according to the figures provided by the Coal Board and, therefore, there is no point in investing millions of pounds to produce coal for which there is no foreseeable demand, which would be produced at a loss and which would embarrass the manpower problem in other pits.”

Parliamentary secretary Reg Freeson broke it down further.

“The important point here, apart from the position of the coal industry in the locality, is that we are taking action to attract new industry to the area” he said.

“There are enough jobs in prospect in the new and expanding industries to reduce the level of unemployment greatly.

“This is the correct solution for the future, rather than reopening the Michael Colliery.”

Tears were shed as former miners and relatives gathered to remember those killed to mark the 50th anniversary of the disaster in 2017.

The Rev Wilma Cairns, of East Wemyss and Buckhaven churches, led the service on Saturday at the colliery memorial in Main Street.

As a minute’s silence was observed, strings of coloured canaries made by schoolchildren and tied to trees to represent the victims fluttered in the breeze.

There are now no active deep coalmines in Scotland.

Conversation