There was nothing glamorous about the lives of Mary and John Curran as they went about earning their daily bread in Dundee in the late 1930s.

She was a part-time worker at the the hairdressing and tobacconist business in Kinloch Street, owned by her brother-in-law James, in addition to her regular job as a cleaner at Green’s Playhouse Cinema; he was a tram conductor on the busy roads through the city.

Yet fate intervened in both their lives in dramatic fashion towards the end of July 1937 when Mary received a visitor at her tenement home in Church Street, inquiring about buying James’ shop which he had put up for sale.

Mary suspected something was wrong

Immaculately dressed, with a brisk attitude to conversation, the woman, who spoke with a pronounced German accent, introduced herself as Mrs Jessie Jordan and explained why she was interested in purchasing the property for her own use.

She was thoroughly professional in discussing her plans for expansion, but something kept nagging away in Mary’s mind, a sense that she wasn’t being told the whole story.

And what a story it was: one involving a Nazi spy ring with links stretching all the way from Hamburg to the United States and which was eventually toppled because Mary couldn’t shake off the feeling that this Jordan character was a wrong ‘un.

Mary couldn’t act immediately on her instincts, or not without any evidence. Even when she found a scrap of paper on which Jordan had written the word “Zeppelin”, it didn’t offer conclusive proof that something was amiss.

Initially, when she showed it to her husband, he dismissed it as the stuff of fairytales and Patrick Robbins, who was John’s boss in the Tramway garage, suggested that Mary was letting her imagination run away with her on the back of having watched too many thrillers, such as The 39 Steps, in various Dundee cinemas.

But Mary was nothing if not tenacious and, a few days later, she discovered another piece of paper hidden between the pages of a child’s school jotter. On this occasion, the slip again featured the Z word, along with a row of 24 numerals which meant nothing to her. Yet, by this stage, she felt sure that Jordan’s regular trips to Germany were nothing to do with her alleged string of hair salons in Hamburg.

And she was right.

She had to be patient, though, and even after mentioning the second piece of paper, was dismissed as having fanciful notions and being caught up in the fixation with spies which was happening in the increasingly febrile climate before the Second World War.

But finally, on November 17 1937 at Kinloch Street, Mary came across a hand-drawn sketch plan of an unidentified coastal installation showing railways, a pier, a number of factory buildings and some hastily-scribbled notes in both German and English.

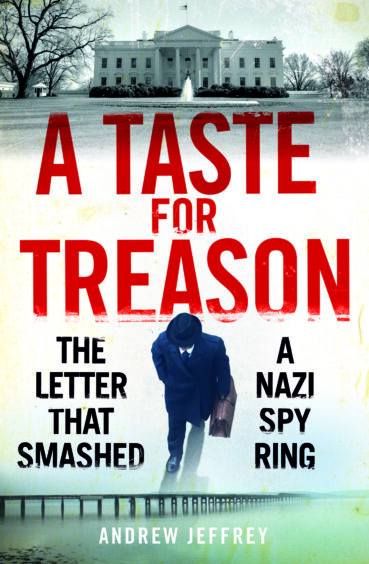

It was a major breakthrough, as author Andrew Jeffrey has revealed in his new book A Taste for Treason, which investigates Jordan’s multi-faceted role in one of the biggest espionage networks ever assembled across different continents.

And, after smuggling the drawing by putting it down the front of her dress and dashing home, Mary at last had the proof she required to disprove the sceptics. If the latter had dragged their heels in previous months, they didn’t hang around in this instance.

Mr Jeffrey explained: “This time, Pat Robbins needed no convincing and took the sketch straight to Detective Lieutenant John Carstairs of Dundee Police, a former Scots Guard who immediately realised its significance and showed it to his boss, Chief Constable Joe Neilans. Dundee’s housewife spycatcher was now taken very seriously.

“[In the days ahead] Friday began with Carstairs arrival at MI5’s B Division offices on the top floor of Thames House in Millbank, London.

“After being shown the mysterious sketch and told that it had been discovered in a shop run by a Mrs Jessie Jordan at 1 Kinloch Street in Dundee, [Colonel] Edward Hinchley Cooke produced an MI5 case file marked with Jessie’s name and surprised Carstairs by saying: ‘Oh, that will be Mrs Jordan of 16 Breadalbane Terrace in Perth?’

“Told by Carstairs that Mrs Jordan was leaving Dundee that same evening and that Mrs Curran suspected she was going to Germany, Hinchley Cooke requested that Jessie should be followed to her port of embarkation.”

The net was closing in, but the full extent of the spy’s activities only became clear later.

The scene was now set for something from the realm of a Hollywood movie. Think The Third Man without the zither. Or The Spy who came in from the Cold minus the ice.

As Mr Jeffrey said: “Camperdown Dock was in darkness apart from the dim glow of a few quayside gas lamps and the swaying deck lights of the Currie Line steamer Courland as Jessie, Mary and John hurried along a rain-swept Dock Street and, watched by Detective Inspector Tom Nicholson, went aboard the ship.

“The Currans came ashore about 20 minutes later and, intercepted by Nicholson as they made their weary way homewards, John told the detective that the Courland would not now be sailing until the following afternoon.

“Mary added that she had asked Jessie if she had enough money for the trip. ‘Don’t worry about me’, came the enigmatic reply. ‘I’ll get plenty of money where I’m going’.”

As a result of Curran’s intervention, the address in Kinloch Street was added to an ongoing mail watch, Jordan was kept under constant surveillance and, soon afterwards, incriminating correspondence from the United States was discovered.

This, among other things, highlighted a plot to assassinate an American army colonel – and Jordan, who had been born Jessie Haddow in 1887, was arrested on March 2 1938.

Chief Constable, Joseph Neilans, had prepared the ground by obtaining search warrants for her premises in Kinloch Street, as well as for her half-brother, Frank Haddow’s house at 26 Strathmore Avenue in Coupar Angus.

On the morning of March 2, two police cars carried MI5’s Colonel Hinchley Cooke, Chief Constable Neilans, DI Thomas Nicholson and policewoman, Annie Ross, to the business address in Dundee. Their guide was Det Lt, John Carstairs, who had started a dossier on the Jordan case in November 1937.

The five-strong party entered the property, finding the accused, whom they detained, and 14-year-old Patricia Haddow, who worked in the shop.

They peremptorily dug up the drains, raised the floorboards, and inspected Mrs Jordan’s former apartment at 23 Stirling Street in Dundee. And eventually, they found a bag containing a stash of airmail letters in a cubicle-cum-bedroom, off the beauty salon, where it later emerged she was spending her nights.

Jordan had been mixing with some very bad company, including Ignatz Griebl, a vehement Nazi who circulated and wrote anti-Semitic propaganda and sent to Berlin a blacklist of American Jews who would be ‘dealt with’ in due course, including New York’s mayor, the legendary Fiorello La Guardia.

The charges

The next day, while crowds gaped at the suddenly infamous salon in Kinloch Street, Jordan made a one-minute appearance in court, during which time she was charged with offences under the Official Secrets Act.

In another country at another time, she might have faced the death penalty. But nobody in authority was keen to pursue such a draconian policy against a woman in her 50s, especially when it emerged she had lived in Germany for many years, following the death of her husband, Karl, whom she had met while working as a chambermaid.

Eventually, in May 1939, Jordan was found guilty of espionage and sentenced to four years imprisonment. At the outset, she was incarcerated at Saughton in Edinburgh, but the experience led to her falling seriously ill and requiring a sub-total hysterectomy.

Just a few months earlier, her daughter, Marga, had died as a result of what her husband, Tom Reid, called “an illegal operation”.

When the Second World War began in the autumn of 1939, she was transferred to Craiginches Prison in Aberdeen, but her solicitor John R Bond – whose firm was based in Dundee – described her as “a model prisoner, who showed off her needlework to the other inmates and exhibited no interest in an appeal”.

He told The Courier she was “not in the least depressed” and, as a consequence of her good behaviour, Jordan was granted early release in 1941 – only to be immediately arrested again and interned as “an enemy alien” for the remainder of the conflict before being deported back to Germany.

Jessie Jordan died in 1954 and it’s difficult not to conclude she was a fantasist who found herself embroiled in a nefarious and dangerous world.

But there’s no doubt life as a spy thrilled her to bits.

Make of that what you will.

A Taste for Treason by Andrew Jeffrey is published by Birlinn.

Conversation