The city’s highest point being set ablaze in a huge bonfire proves that spontaneous shows of loyalty for a monarch are nothing new in Dundee.

Members of the public united in grief and lined the streets in Dundee when the Queen’s cortege passed through the city following her death on September 8 aged 96.

Nowadays, in this digital age, where we have access to television, radio, telephones and the internet, we can quickly come together to show our strength of feeling.

However these feelings were much harder to express in the 19th century.

One means of doing so was to light bonfires on hilltops, which acted as beacons of unity, signalling to neighbouring communities that they shared in their grief or joy.

They would be lit in times of triumph and tragedy at places such as Dundee Law which was a popular location for such bonfires in the 19th century.

Dundee Law was top bonfire spot

Author Tom Welsh has spoken about one special event in 1887 which he uncovered during research for his new book titled Hilltop Bonfires – Marking Royal Events.

Tom said: “There has long been a custom in Scotland to light bonfires on hilltops as a way of celebrating marriages, births and the coming-of-age of heirs to estates.

“When Queen Victoria visited Scotland in August 1842, fires were lit on hilltops for twenty to thirty miles in all directions around Edinburgh while the royal fleet was moored in the Forth Estuary.

“When Queen Victoria reached the Tay estuary in 1844, on her journey to Blair Castle, bonfires were lit on the hills on both sides of the Tay.

“Such displays of loyalty aroused a great deal of interest in the newspapers, and descriptions were relayed around the south of England.

“It inspired English estates to adopt the same mode of celebration.”

Hilltop bonfires soon became a common feature of royal events.

Tom said: “Scotland, with such a long history of building big bonfires, was well placed to impress.

“So, when it came to Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887, a call went out to light bonfires on as many hilltops as possible around the Kingdom.”

The bonfires for Queen Victoria were arranged to be lit at 10pm on June 21 1887.

Dundee would take its signal from Norman’s Law, west of Luthrie, five miles south of Inchture.

However, Dundee decided to light an additional bonfire several days earlier, on Dundee Law, to open the celebrations.

It was due to be lit at midnight on Saturday, June 18, but the Presbyterian Church objected to the fire lingering on into the Sabbath.

So instead, it was lit on Friday, June 17.

June 17 1887

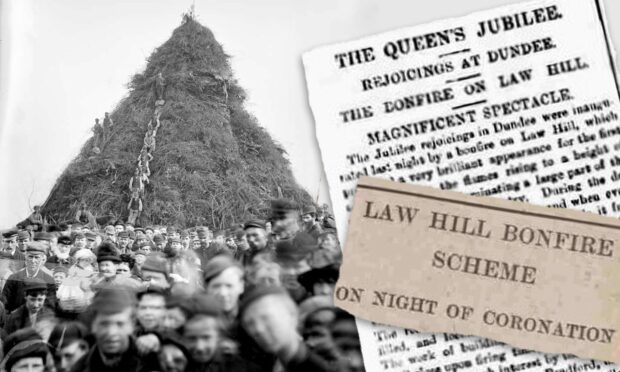

Teams of workmen started building the bonfire early on Wednesday morning.

Tom said: “They carried on until after midnight, and did the same again on the Thursday.

“On Thursday afternoon, 500 children helped carry fuel.

“The fuel was conveyed to the foot of the hill at the south-east corner, and then dragged up by men and horses.

“About 500 loads of fuel were carried there.”

The base of the bonfire was 50 feet (15 metres) square.

Running to about 50 feet high, the bonfire was constructed around a central flagpole; a pine tree, stripped of its branches and bark.

The Courier reported: “All day the work was carried on vigorously by the workmen, and in the afternoon they were assisted by a volunteer army of about five hundred children, who rendered valuable aid with the work.

“About five hundred loads of fuel will be required to complete the bonfire.”

Adding fuel to the fire

“The material consists of immense quantities of brushwood and cartloads of every description of old timber.

“Amongst the heterogeneous materials are fragments of old boats and ships, old palings, clothes poles, rafters and flooring of old houses and old tar barrels.”

“The stuff was carried up to the south-east corner of the hill, and from thence it was dragged up by horses and men and boys.

“By about ten o’clock the pile had been raised to between 20 and 30 feet, and at the same rate of progress it will take hard work to get it finished before the hour appointed for firing it.”

Prior to lighting, a flag was hoisted to the top of the central pole before 150 gallons of naphtha were poured over the bonfire to saturate the fuel.

On the evening of Friday June 17 1887, an immense crowd gathered on the hill.

All around the bonfire, the crowd appeared in dense masses, and by a wise arrangement of the police they were kept at a safe distance from the fire.

Eagerly waiting for the blaze, the kids started to amuse themselves by lighting small fires on the slopes of the hill.

Up in flames

The Courier reported: “The signal was given, and the young lady gave a firm pull of the string.

“A dull explosion and a bright flash followed, and a long tongue of flame leaped in the air from the centre of the mass, twining round the pole and igniting the flag in a second. Simultaneously with the flash the whole mass leaped into flame.

“The brushwood having been thoroughly saturated with naphtha, caught fire in an instant.

“A ringing cheer rose from the crowd as the fiery tongue shot into the air, and again and again.

“The cheering was taken up by the crowds that lined the lower slopes of the hill, and wafted over the whole town.

“As the flames increased the heat became intense, and the eager crowds which had for hours covered the crest of the hill gradually began to retreat to the lower plateau, from which the conflagration was witnessed with more comfort and safety.”

Tom said: “The bonfire was at its most spectacular for half an hour, but it continued to burn significantly into the night.”

The crowds continued to linger in the streets until the early hours of the next morning.

A fresh bonfire was then erected for Tuesday night.

Tom said: “There were many bonfires lit all across Tayside and Fife on June 21.

“One of the most spectacular was at Knapp, near Inchture, probably on Dron Hill.

“A great attraction on these events was to see all the other fires lit up on the surrounding hills, connecting communities.

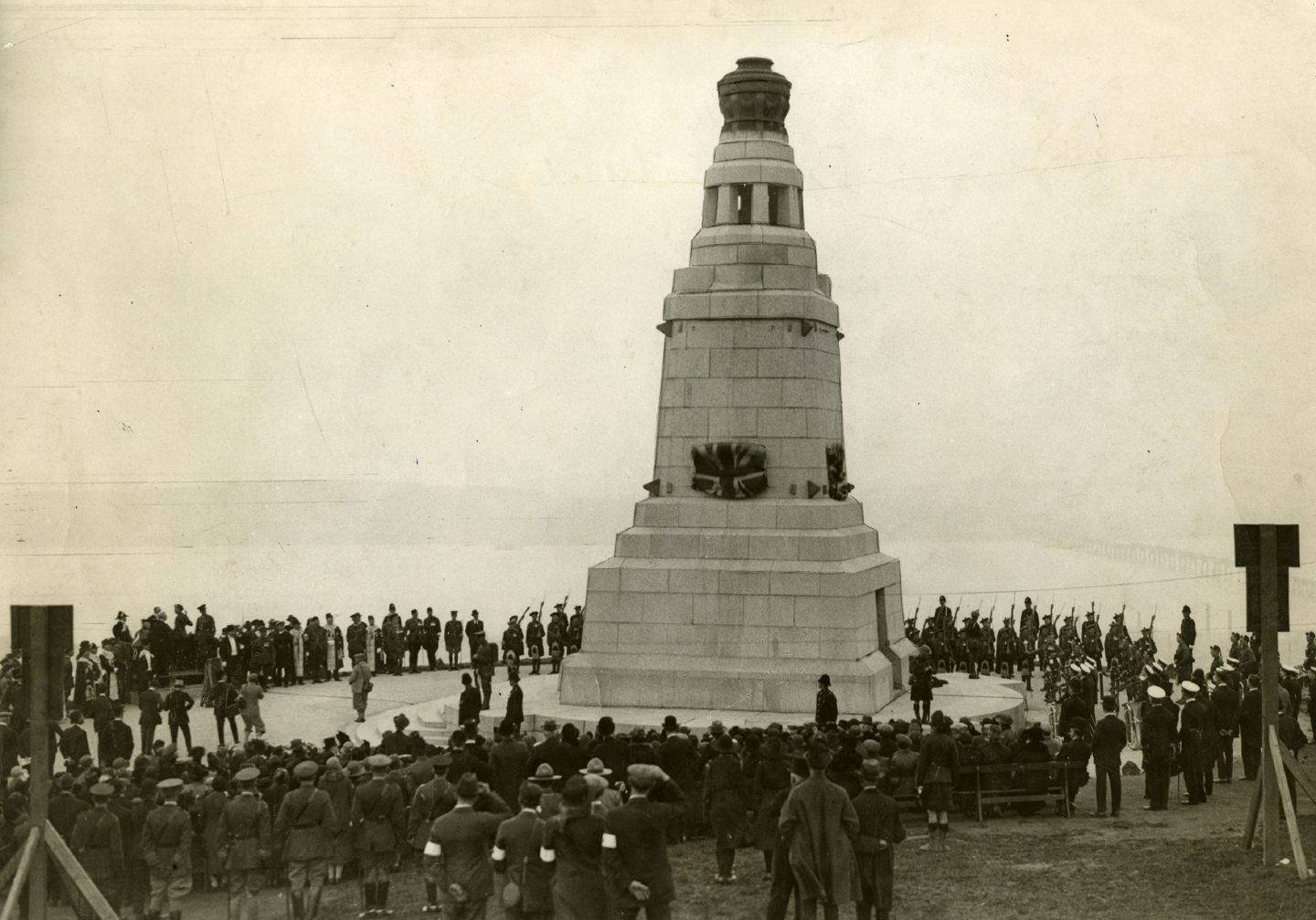

“Bonfire networks of this sort continued to be used for celebration well into the 20th century.

“However, soon their impact on the environment became an issue.

“Latterly they have been superseded by braziers mounted on posts.

“Often these are not on hilltops, but where people can safely gather to watch.”

Dundee Law features fortification remains, and archaeologists have also found evidence of vitrification where stones have been fused together by melted minerals.

Tom concluded: “These are attributed to prehistoric times, but archaeologists rule out bonfires as a factor.

“It is argued that no-one could ever carry up enough fuel to produce the temperatures required.

“Perhaps it got hot enough on June 17 1887.”

Tom Welsh’s book, Hilltop Bonfires: Marking Royal Events, is on sale now.

Conversation